Lebohang Kganye’s Ever-Evolving Journey Across Memory and Medium

The South African artist's approach to photography is being celebrated throughout this year, at solo exhibitions in the US and UK, group showings, the Venice Biennale and more.

Lebohang Kganye's work will be shown in various exhibitions this year, from California's ROSEGALLERY to the Venice Biennale.

2022 is turning out to be a big year for South African visual artist and photographer Lebohang Kganye. She recently won the Foam Paul Huf Award, presented annually to a photography talent under the age of 35, as a means to further their artistic development, and has a busy schedule ahead of her. Just this month alone, her first solo show in the US, What Are You Leaving Behind, wraps up at ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica, California, she’ll be one of three artists representing South Africa at the 59th Venice Biennale, and a solo exhibition of newly-commissioned video work opens at the Bristol Photo Festival.

Kganye’s work will also take her to Germany for K21: The Walther Collection, a group photography show in Dusseldorf, in conversation with an exhibition curated in 2010 by the late, great Nigerian curator and critic Okwui Enwezor. Then, as the first African photographer to win the international Grand Prix Images Vevey 2021/2022, she’ll be debuting a newly-commissioned installation at Festival Images Vevey in September in Switzerland.

Back in Germany, she’ll also be included in the Hamburg Photo Triennial and group show at Syker Vorwerk, Centre for Contemporary Art, and she’s been invited to participate in the Artist Meets Archive program of the International Photoszene Festival in Cologne. Topping it all off, Kganye has been selected as one of five finalists of the MAST Foundation for Photography Grant in Bologna, Italy.

For all the places her work is set to take her, Kganye is rooted in South Africa. Born in 1990 in Johannesburg, where she currently lives and works, she was always interested in literature and oral storytelling, and worked in television on telenovelas, where her fascination with lighting and staging translated into a passion for theater. She received her introduction to photography at the Johannesburg Market Photo Workshop in 2009 and says, “the influence is not just visual for me, which is why my art takes on different forms. I’m always visualizing what I’m reading and creating that.” She explains that her installations, film animation, set design, collage, and non-traditional use of photography are connected — “it’s all interested in memory and fantasy, theater and staging/stages, oral narrative and family archives.”

The ROSEGALLERY showcases eight years of Kganye’s career, weaving together three formative series, while also bidding farewell to the grief and loss that informed much of that earlier work. Ke Lefa Laka / Her Story (2013) was a response to the death of her mother and the break in ancestral ties. Worried that she was beginning to forget how her mother looked and sounded, she photographed herself recreating her mother’s old photos, dressed in the same clothes and mimicking the same poses. Then she made digital photomontages inserting herself into her mother’s snapshots, creating a ghost image in communion.

Her Story (2013), as seen at the ROSEGALLERY exhibition, was a response to the death of Kganye's mother and the break in ancestral ties.

Photo: ROSEGALLERY

Like all family albums, this version of her mother is part fantasy. “My mom worked as a factory worker since her twenties,” Kganye told OkayAfrica, “but there are no photos of her in her overalls, which she wore daily.” Prior to the era of cell phones, many Black South Africans had to rely on street photographers. If one was “passing by and you could flag him down, then the whole family would quickly dress up! This woman who’s always dressed up has come to represent my mother.”

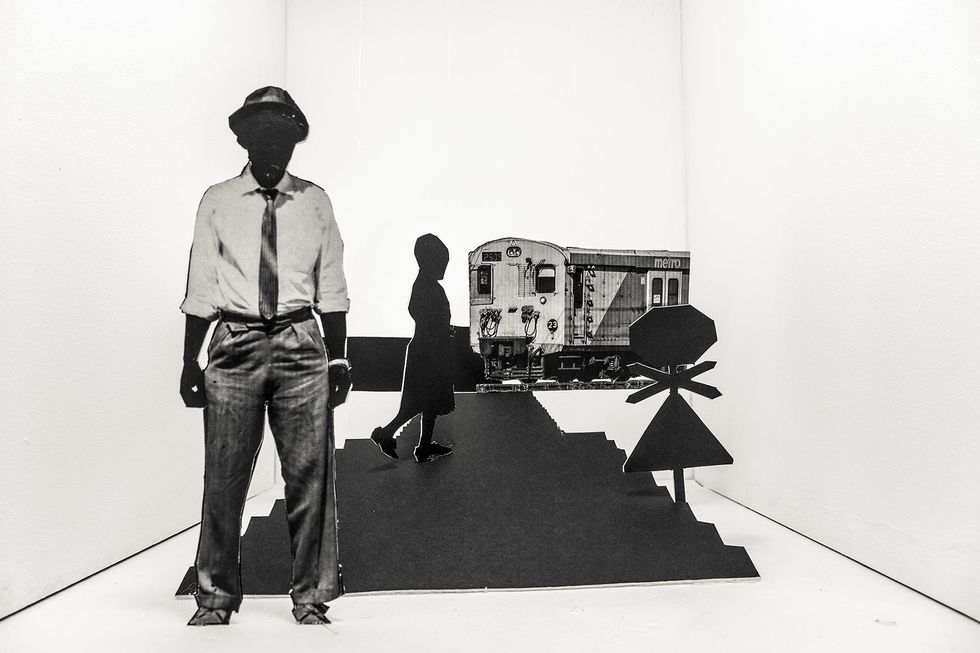

The artist’s fascination with albums as both archive and performance, where families curate aspirational identities, and with photography as staging, drives the second series, Reconstruction of a Family (2016), a series of black and white prints that resemble collage but are actually photographs of box dioramas. Using cut-outs of family members, both silhouettes and photos with the faces replaced by black cut-outs, Kganye first creates an installation inside a box and lights it for shadows.

She then photographs the work to exhibit as stills. The third iteration is an animated film short. Here, personal history reveals national history, as her family was displaced and resettled due to apartheid’s punishing laws. Both the themes and specific silhouettes evoke Pied Piper's Voyage (2014), her first animated film, which chronicled her grandfather’s arrival to the city from the homelands, through a series of intricate dioramas in which Kganye, dressed in her grandfather’s suit and hat, interacted with life-size cut-outs of her family.

The artist’s fascination with albums as both archive and performance, where families curate aspirational identities, and with photography as staging, drives her series, Reconstruction of a Family (2016).

Photo: ROSEGALLERY

The film version of Reconstruction of a Family, Ke Sale Teng (2017) demonstrates Kganye’s current interest in children’s pop-up books, with walls folding down, floors flipping up, and furniture and figures popping into place. She is developing a life-sized, mechanized pop-up book for Festival Images Vevey, employing set design in conversation with Ta O’Reva, Malawian author Muthi Nhlema’s sci-fi thriller that imagines Nelson Mandela brought back to life in a post-apocalyptic South Africa.

Tell Tale (2018), the final series on display at ROSEGALLERY, represents where Kganye’s practice is headed. While at a residency in the Karoo, Eastern Cape, she read two plays by playwright Athol Fugard based on local people and incidents, and a chapter from author Lauren Beukes’ Maverick: Extraordinary Women from South Africa's Past. Hearing differing versions of events from locals sparked her interest in the fluidity of storytelling and gaps in memory and public record. She staged these oral community accounts as miniature theater sets with silhouette cut-outs of the characters.

Kganye's interest in the fluidity of storytelling and gaps in memory and public record is explored in her Tell Tale series.

Photo: ROSEGALLERY

Kganye’s engagement with orature and language, evident in the titling of more personal projects in her mother tongue Sesotho, informs her new work for the Bristol Photo Festival. Site-specific to the Georgian House Museum, a former sugar plantation and home of an 18th-century enslaver, Kganye’s three-channel video installation involves performance, healing, naming and Sesotho praise-songs. It’s titled Dipina tsa Kganya (2021); dipina means “songs'' in Sesotho, while kganya is both the word for “light” and the etymology of her last name: Kganye.

It seems only fitting that South Africa’s pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale is conceptualized around the theme of “Into the Light” – a reference both to artists leading the way out of the darkness and confusion of a worldwide pandemic, and to the Biennale’s overall theme, “The Milk of Dreams.” The title comes from a children’s book by British-born, Mexican-based novelist and surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, in which otherworldly creatures constantly transform in a magical world.

In what will surely be a highlight for Kganye's work -- exhibiting at the world's premier art exhibition -- the theme is apt for how the artist views her work: “We create other worlds through photo or moving images,” she says, pausing briefly to consider What Are You Leaving Behind before hurtling “Into the Light.”

- 7 African Curators You Should Know - OkayAfrica ›

- In Conversation with Laolu Senbanjo on Damien Hirst and Cultural ... ›

- A New Exhibition In Accra Celebrates The Future Of Ghanaian ... ›

- Photos: Inside Ghana's First-Ever National Pavilion at the Venice ... ›

- South African Artist Simnikiwe Buhlungu on Creating the Sound of Dreams - OkayAfrica ›