Too Black to Be Dominican: The Olympic Medalist Derided as Too Foreign

When a dark skinned Dominican won an olympic medal last week he was immediately derided by countrymen as too foreign. Too Haitian. Too black.

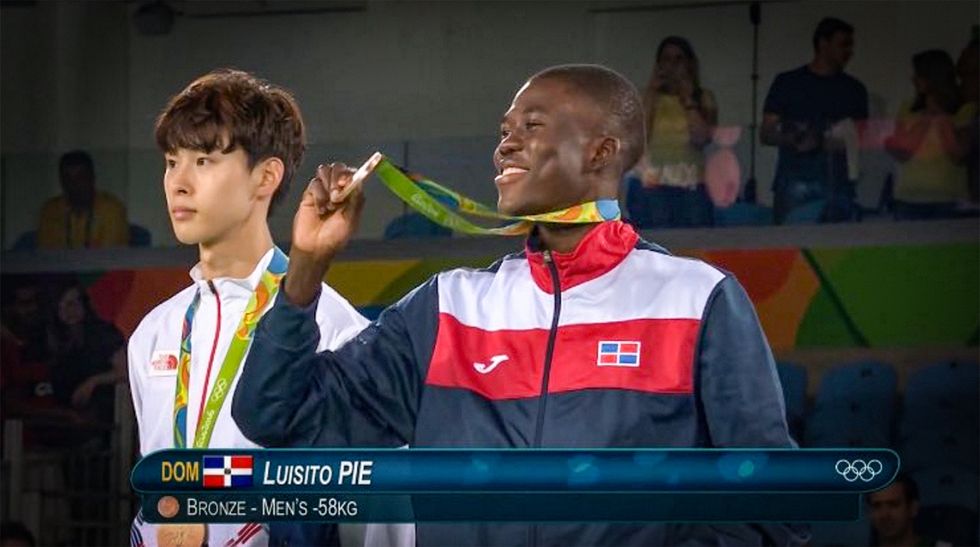

Last week, Luis “Luisito” Pie defeated Spain’s Jesús Tortosa in the 58 kg taekwondo bronze fight, and emerged with the first medal of the Rio Olympics for his country—the Dominican Republic. However, a feat that should have brought joy to sports fans throughout his homeland, reignited a national debate about nationality, race, and who qualifies as Dominican.

Despite being born and raised in Bayaguana, in the Dominican Republic, Pie was immediately questioned on Dominican media and social media about his Spanish, his last name, and the fact that his father’s family came from Haiti. Pie dedicated his bronze medal to “the ten million Dominicans,” and waved a Dominican flag proudly in celebration, but his Haitian heritage meant, for some, that his allegiance to the country could not be trusted.

Haiti and the DR both share an island in the Caribbean, known as La Hispaniola, and thus the two countries have been intimately connected since their inception. But tensions between both countries have also been commonplace. A growing anti-Haitian, nationalistic movement took over the Dominican part of the island recently and in 2013 the Dominican government enacted a ruling, retroactive for more than 80 years, that stripped citizenship from anyone who couldn’t prove “regular” residency for at least one parent.

Tremenda foto de @LuisitoPieTKD pic.twitter.com/CvVxhsqLXe

— Dionisio Soldevila (@dSoldevila) August 18, 2016

This disproportionately affected those Dominicans of Haitian descent, who (counting those with and without legal status) numbered around 700,000 in a country of 10 million. Those with Haitian descent who couldn’t prove they and their families were born in the Dominican Republic, even if they had lived there their whole lives, were given a deadline of June 17, 2015, to leave the country. Many did flee, fearing violent persecution. Many more stayed, but became legally second-class citizens.

Luisito and his family, confident in their status as Dominicans, stayed, though they weren’t safe from harassment. According to his family, Pie was almost denied a passport to go compete at the Central American Games in Veracruz, Mexico, in 2014. The family also said that the Taekwondo Federation interceded, and he was eventually allowed to receive his passport and go to Mexico, where he won a gold medal.

Back then, Pie’s Dominican-ness was also questioned, and many commented that Luisito, despite being Dominican-born and having Dominican citizenship, should be competing for Haiti. He, nonetheless, said then that he felt sure and proud of his Dominican roots, and that he paid no mind to negative comments.

After winning his first Olympic medal (the seventh ever for his country), Pie similarly spoke of the pride he feels for representing the Dominican Republic. But, unfortunately, as a black Dominican of humble background, he’s still victim of a prevalent kind of discrimination that targets both ethnicity and race.

Though the Dominican census has not asked about race or ethnicity since the 1960s, an OAS survey done in 2006 found that about 90 percent of the country considers itself as “dark skinned” (67.6 mulatto, and 13.6 percent black). Yet blackness in the national discourse is often associated with foreignness and, especially, with Haitians.

Gina Athena Ulysse explained this perception in a Latin America is a Country post about the anti-Haitian laws in the DR:

This cleansing, I would add, is a rejection of a certain kind of Black. Blackness that is too African. Despite our somatic plurality and the color gradations we encompass, Haiti and Haitians have always been portrayed and understood as that kind of Black. A Blackness of a particular kind that, truth be re-told, radically changed the world. It was an avant-garde Blackness that not only pulled off a successful slave revolution, which caused the disorder of all things colonial, but also brought the sanctity of whiteness into question. The Haitian Revolution disrupted the notion that Freedom (with a capital F) was the sole domain of whites or those close to whiteness. Indeed, the value ascribed to those Black Lives continue to deteriorate. Moreover, those among us who are visibly marked with that Blackness have had to continually dissuade folks that we are not genetically coded to be their property or the help.

But Pie, once again, is Dominican. These fears are not his own, but are encoded in those Dominicans who refuse to think that a person with any trace of Haitian heritage can share a nationality with them. It is perhaps telling that Luis Pie is also the name of a story published in 1942 by Dominican writer Juan Bosch, and of its protagonist: a Haitian man subject to violent persecution after being unfairly accused of starting a crop fire.

The Luis Pie of literature represents the hopelessness against xenophobia, the struggle of Haitians in the Dominican Republic and of their descendants to be treated as equals. There is still hope, however, that the Luis Pie of taekwondo might become synonymous with overcoming discrimination, and claiming your ground as an integral part of the country.