'The African Lookbook' is 100 Years' Worth of African Women's Global Influence

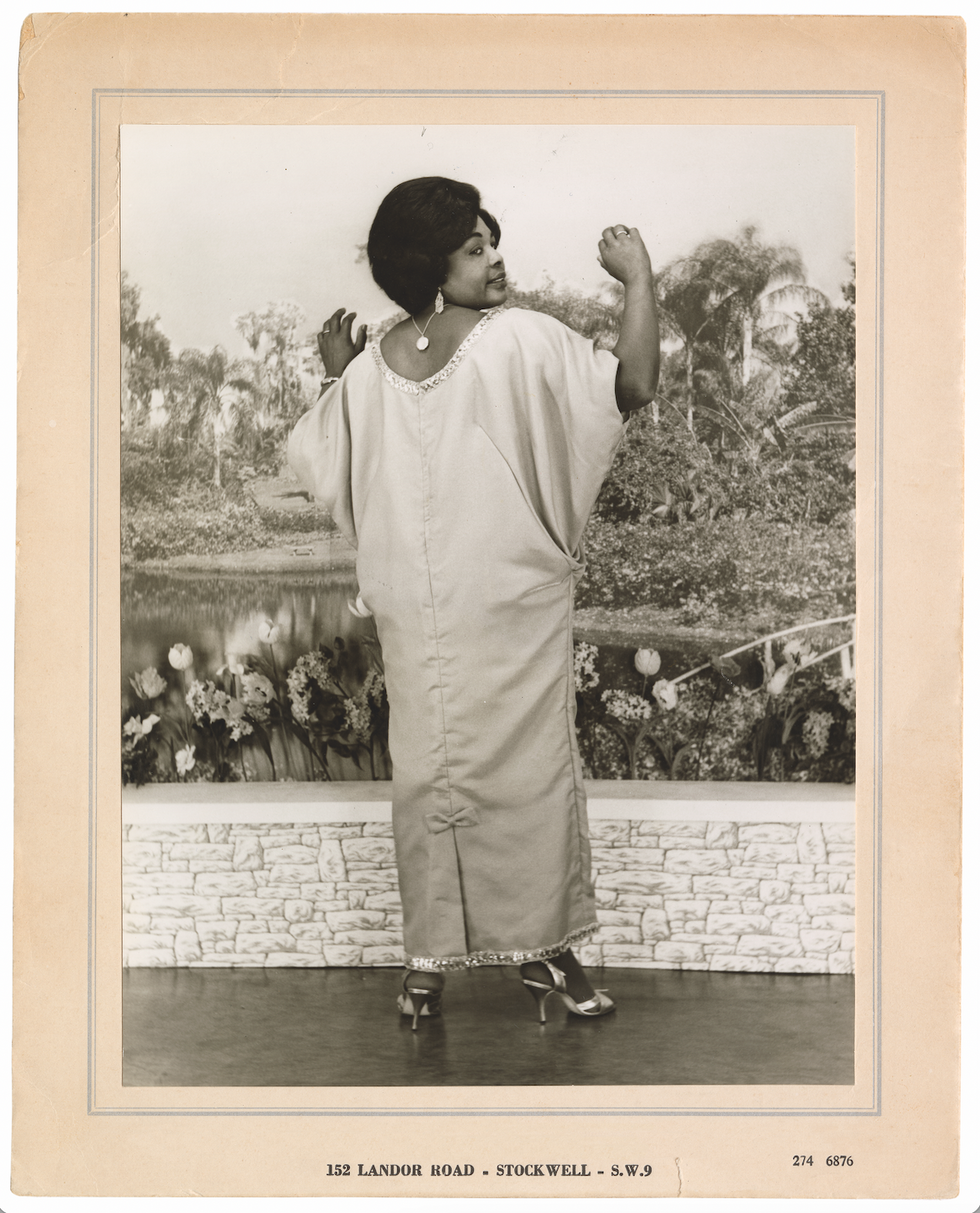

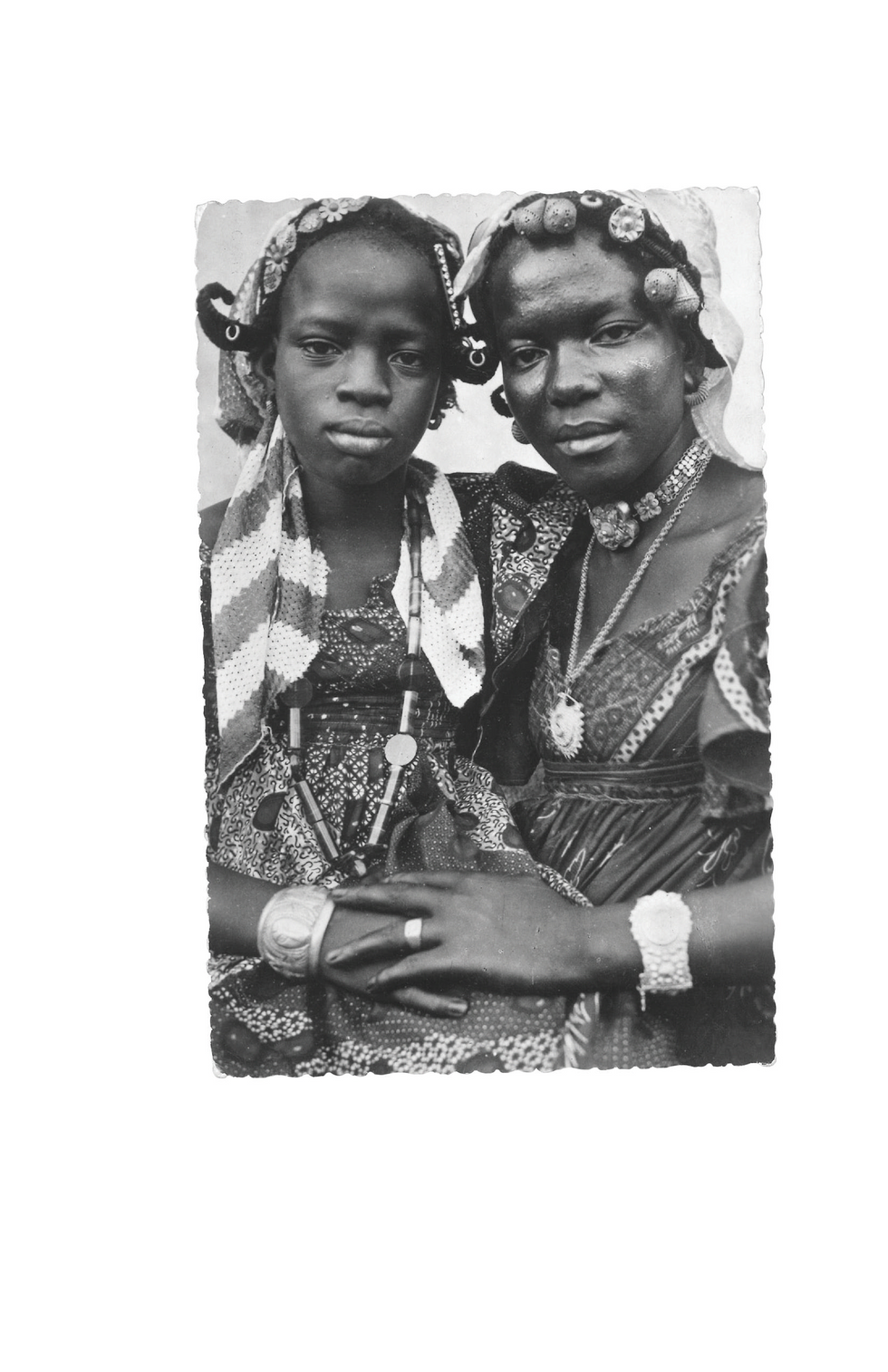

Catherine E. McKinley's 'The African Lookbook' documents 100 years of African women in front of and behind the camera as well as Africa's unmistakable, yet often trivialised, influence on fashion as we know it today.

- Untitled, Undated, Unknown, Senegal

African-American writer and curator Catherine E. McKinley's The African Lookbook is a remarkable repository for African women's rich history, their influence on global fashion and photography spanning 100 years.

Published in January of 2021, the book comprises photographs collected during McKinley's numerous travels across Northern and Western Africa over the years. The African Lookbook is an extensive archive currently documenting the role of mainly West African women in fashion and how both the thriving textile trade from a century ago as well as colonisation, resulted in the fashion landscape we've come to know today.

In what remains an incredibly white-washed fashion industry filled with cultural appropriation, very little credit given to Africans and Black women who have (and continue to) contribute to the industry, The African Lookbook upends that reality within its pages. While popular designers, the likes of Tory Burch, Marc Jacobs and more, have been at the receiving end of public backlash for appropriating Black culture, McKinley's book highlights just how far back many of the runway trends we see today were actually pioneered by African women whose contributions were simply erased over time. Take for instance Stella McCartney's controversial 2017 Spring collection which comprised vibrant ankara prints (from West Africa) but had very few Black women in the show overall.

In addition to fashion, The African Lookbook explores Africans behind the camera. It seeks to name image-makers, to give credit where credit has been so long overdue, and chronicle what McKinley thinks of as the African-Atlantic—the coastal countries that were trade centres reaching into the interiors.

And so we caught up with McKinley to talk about her growing collection of insightful photographs, how the concept originated and what the bigger picture (pun intended) is for the collection itself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You go by a number of labels and titles. But how would you describe yourself to our audience as a creative, as a creator?

I think of myself probably primarily as a writer but I'm moving more and more into art. I'm thinking more about how the archive can be used for public exhibition, et cetera. Let's say writer and curator is probably the best thing. But you know, like most of us it's so fluid and a lot of different things going on at once.

How did the lookbook, as a concept and as an archive come about?

When I graduated from college, I made my first trip to West Africa: Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal. And when I was traveling, people would give me photographs. When you leave, somebody would present you with a photograph and we kind of did the penpal kind of thing. And the photos, they were really lovely photographs. I think one of the first ones I got was from somebody's houseboy and he gave me a photo of himself in his Sunday best. He was holding a chicken and he cooked it when I was there. So that had a lot of meaning. I knew also that it wasn't a cheap thing for him. It's something he dressed and paid money to have a really nice photo taken of himself. I collected many others, and they were the root of the collection, though at that time they were just keepsakes.

Then I brought them home and this was in 1991. I was always interested in photography, but by 1997, we started to see Seydou Keita and a few others. They made their way to the US and a huge exhibition of African photography. I met Seydou Keita too when he was here. And it was just mind blowing to me to see his work.

I just got into all this stuff around the politics of what was being done, but I was also really in love with the photos. Every year I was going to Africa, mostly West Africa and I was looking more and more at photos and also doing fashion research. As time went on and there was more and more attention to African photographers, I started really asking questions, like, "What is this all about? What's this dynamic about? How does somebody's personal photo become an art object? And what does that mean historically and politically?"

Would you say that your personal connection with the continent is a result of your travels?

It happened even before them. I would say, even as a really young child. I was adopted by a white couple. It was like, "Okay, what does this mean?" But then it's like, "Oh, you are Black but you're Afro-American." So I was like, "Afro-American is African." And then I thought, "Okay, so I'm African." I started reading a lot of Pan-Africanist stuff very early because I was looking for Black books and there was a university nearby.

I was introduced really early to Pan-Africanism. Then the irony is that my biological father, when I did find him, is African-American, but his grandparents were from the Cape Verde Islands and he then married a Ghanaian. So I have all these Ghanaian half-sisters. I always felt myself as very much a part of Africa.

Do you still identify as being African now that you're much older?

I won't use it because people don't understand what I'm saying, but yes, in myself and at this point in my life, I probably have spent more time living in Ghana and traveling to Ghana in particular. So it's a big part of me. When I got there, I was like a fish to water. Some people go and they have all these conflicts and whatever. For me, it was like, "Okay, this is my corner of the world."

There are quite a number of photographs in this lookbook. Are there any ones in particular that really stand out for you personally and why?

It's hard because in selecting, I was talking to somebody about this yesterday, I never buy or take a photo that I don't really have a connection to. Sometimes I'd say, "The image is okay." But yesterday, I found something that was taken by a Senegalese photographer and I think it's in Gabon. It was 1911 and the photo itself was landscape. It's not a really remarkable photo, but I was like, "This is a Senegalese photographer in Gabon in 1911. So who's going to question that?" So sometimes I have that sort of response to things but every photo, I have some attachment to.

In the book, the spread at the back about independence. There's a woman at the back named Korama and she gave me some of her own pictures. They were pre-independence, so the '70s. They're just really brilliant. She's a stunning woman. She's so beautiful and the photos are beautiful. I think those are probably my favourites.

In what ways would you say, if at all, that this particular project is perhaps radical or revolutionary seeing as there is currently nothing like it?

It's really interesting. Especially because when we talk about Keita hitting the West in 1996 until now, it's a little bit shocking that nobody's done something similar. But I think it's revolutionary in the sense that nobody's looking at women in any way. They're just kind of saying, "Okay, women are looking back at the camera and there's a power issue." That's important, it doesn't go all that far. But this really is capturing the earliest images through. And the book doesn't go through contemporary images, but the archive does. So I think that in and of itself, positioning women in that way is absolutely revolutionary.

Women were the disproportionate part of the archive, of the colonial archive in particular. And then the African photographers, they were mostly photographing women. So how can anybody have skipped over this? That's a funny thing. People talked about fashion, but for the most part, they haven't really looked at women at all. And my little project right now is to figure out who were the earliest African female photographers. There's almost no evidence of anybody up until the independence era. There's one woman from Nigeria in the 1920s. I have to check the date, but I think it's the 1920s. And I think she owned the studio—a big deal.

Looking at the fashion industry right now, it's very much whitewashed. And very few instances exist of Africa having been given credit. In what ways do you think that this lookbook challenges that reality?

I was looking at a magazine yesterday and I think people would argue that a blouse is a European form but I don't think so. Yes, a blouse in the way we know it came from Europe through the missionaries, but the way it's been Africanized, I don't think that people realise that. But if you look on any fashion page at the moment those are African sleeves, a Black woman's S-curve in many dresses. At New York University, I was doing an arts degree but I I did a lot of costume courses. They taught half-an-hour's worth of non-Western fashion and this is one of the leading costume programs in the world. There's just such huge ignorance, even in the way that people talk about what is traditionally African.

There's always been this idea of African women have always liked what's the latest fashion. As much as they like tradition, it's also like, "What's new?" They're always pushing the trends and that's been a historical reality. So the idea of, "Oh, she's a very traditional something," what is tradition? Tradition has always been extremely dynamic. I think we'll have to think way beyond that as well. And if you go back to West African traders centuries ago in particular, it was a cutthroat business to trade textiles. So, it's like, there's so much intelligence and agency in African fashion. It's not just like, "Oh, this tradition needs to put this on over and over and over again."

A lot of your photographs focus on the Western parts of Africa; countries like Niger, Morocco, Angola. Is there any desire to expand and add photographs from other parts of the continent?

Absolutely. I've done some writing about Namibian women's fashion, more contemporary fashion. And I want to do much, much more. The book goes from Morocco to Congo, mostly on the coast, and then it goes up into West Africa, but I had to do that because I can't do 54 countries.

It was exhausting. But at least there was a clear network because the photographers were moving along the same routes as the fashions. So it was really easy for me as I knew the trading routes and the exchanges whereas a lot of Southern Africa, I don't know so well. I've never been to East Africa. I've been to the West and the North. South African fashion, for example, is it's own culture. It's a whole other thing.

Before COVID-19, I was talking to people about doing some exhibitions in Ghana and Kenya. We were talking about doing exhibitions and the planning was in place. Part of the reason for having the archive and then the book is that I want there to be much more interaction around that stuff. I don't like the idea of the photo as this private art object that belongs to me. I really want to put them in places that make people interact and think about them.

What is your biggest hope for this lookbook and I suppose for the archive as a whole?

The lookbook, it's a love letter to the ancestors and it's a love letter to us, who are the living and who come from the women that are in the book. Edwidge Danticat, in the intro, talks about it as a community album. I have that feeling like it belongs to all of us and that it's in some way for all of us. So I want people to have that pleasure in knowing. I also want to change the narrative of men and Black women, in art and history, etcetera. The potential is everywhere. We all have family pictures, and I think that it's really nice to be able to value them and to look at them differently.

I have friends that have seen the book and I know they have brilliant photos at home. They're like, "Oh, we have this same kind of photo of my grandfather, my grandmother or whatever." I think that it's possible that you may have looked at that image of your father and be like, "Oh, that's a dirty old photo." But it has the potential for so much more.

For anyone interested in knowing more about the lookbook and accessing it in some way, what are some of the avenues with regards to that?

Well, I'm hoping that we're going to get it to South Africa. That we're going to get a publisher that will buy it or somebody that will work with the US distributors and England. So that's wonderful. But I have a website and although it doesn't have everything, it has quite a bit. So people can access us either on Instagram or this site. And the other thing is that there are some images in the book by Frida Orupabo. She's Nigerian and she does collage work using photographs. She's really brilliant. She was in the 2019 Venice Biennale, and she's blown up quite a bit. But I asked her if she wanted to do something with the archives. So she went in and she made these brilliant collages where she just upturns everything.

The African Lookbook can also be purchased here.

Editor's Note: Catherine McKinley is of African-American heritage. She was adopted by a white couple as a child although her biological father is African-American with grandparents of Cape Verdean descent.

- Anunaka's South African Photos Confront the Fear of Freedom ... ›

- Black Social Photography in South Africa: Before & After - OkayAfrica ›

- In Photos: Senegal's Joyous New Year's Celebration, the Fanal ... ›

- A Yoruba Festival Tradition Continues: 50 Incredible Photos ... ›

- Check Out These Moving Photos from Benin's Royal Court ... ›

- Rare Photos From 1950s Senegal Tell A Story of Political Change ... ›

- 5 South African Photo Books to Check Out - OkayAfrica ›

- Arlette Bashizi Wants to see More Congolese Women Photographers - OkayAfrica ›