South African Director Oliver Hermanus on Remaking a Classic

The award-winning director behind Skoonheid and Moffie tackles his first film set outside his home country -- a reworking of auteur Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru -- which is premiering at this year's Sundance Film Festival.

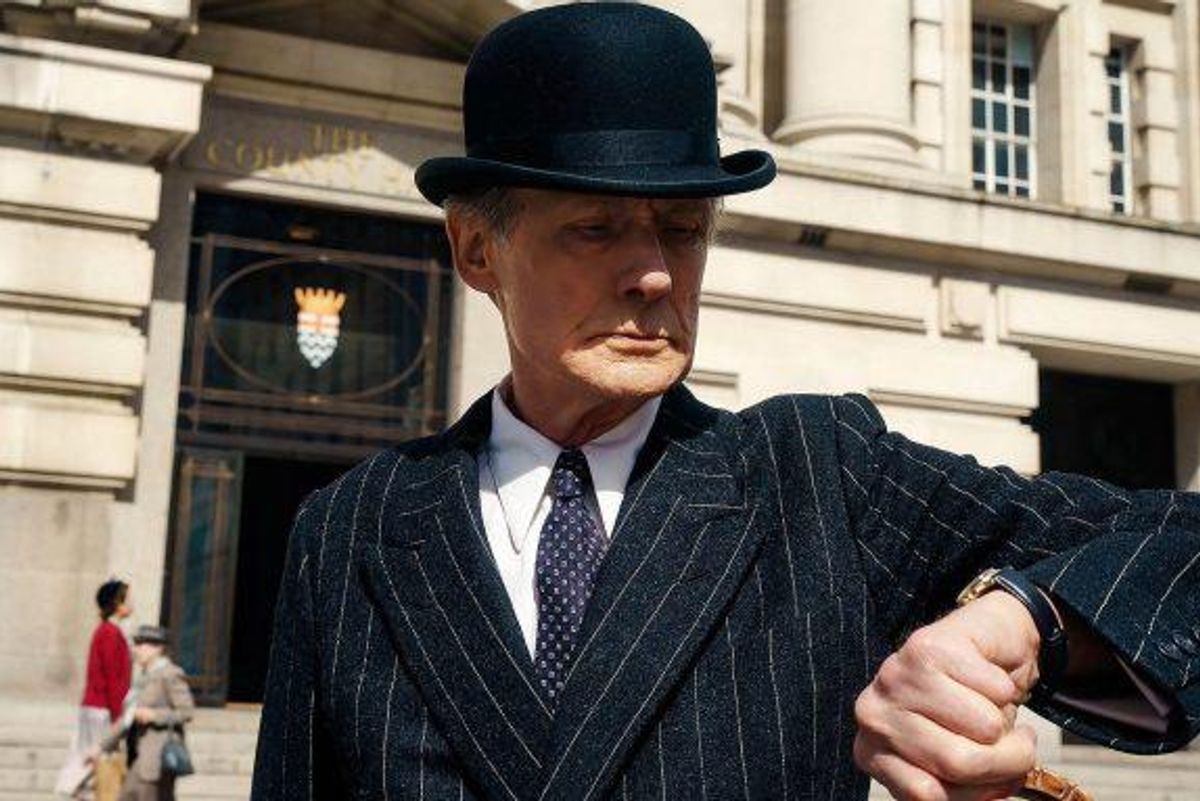

BAFTA-winning actor Bill Nighy stars in South African director Oliver Hermanus' latest film, Living.

In Living, Oliver Hermanus’ latest film, Bill Nighy takes on the role Takashi Shimura earned a BAFTA nomination for playing in the 1952 classic, Ikiru. Except Nighy's not Mr Watanabe, he’s Mr Williams, a British version of Shimura’s workaholic who finds out he only has a short time left to live. Revered auteur Akira Kurosawa’s film made its premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1954, where it would go on to win him a special prize of the senate of Berlin, before garnering acclaim for many more years to come. So, too, is Hermanus' remaking of the story bowing at a film festival, and so far, it's also been earning the South African director high praise.

Born in Cape Town, Hermanus has steadily built his career on South African-centric stories. Whether it’s the portrait of a Mitchell’s Plain mother caught between poverty and violence in Shirley Adams or the experience of gay recruits conscripted into the army in Moffie, Hermanus’ films speak to various realms of South African life. Living is his first venture outside of South Africa – not just in storyline, but in cast and crew, too. The screenplay is by Nobel and Booker Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro (The Remains of The Day) and Hermanus was brought on as director by the producers.

From debuting his first film Shirley Adams in 2009 in competition at the 62nd Locarno Film Festival, followed by Skoonheid (Beauty) at the 64th Cannes Film Festival, and The Endless River at the 72nd Venice Film Festival, where it was the first South African film to be invited to the main competition, to his fourth feature, Moffie at the 76th Venice Film Festival in 2019, Hermanus has cemented his reputation as a filmmaker to watch.

He spoke to OkayAfrica about why he wanted to take on a classic film and the challenges that came with it.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What were your first thoughts when you were asked to take on an English version of an Akira Kurosawa classic?

It was definitely about Kurosawa and the existing film but it was very much about Ishiguro, just knowing that he was a scriptwriter and that there was a real potential to work with him. Bill, the same thing. Knowing that it was written for him and that it was tailored to him. Ishiguro wanted him to do it; envisioned him as the inspiration for the whole gestation of this project. So I was kind of given something that people were very precious about. And there was a real sense of not f***ing it up, in the words of RuPaul. So I was going, 'Can I do this?' It's a bit like a marathon, going 'Am I fit enough? Do I have the skills?' And I think the real turning point was actually Ishiguro. He was very confident about the whole project; confident about retelling it, confident about me, confident about why, confident about Bill, and I took that and ran with it.

The producers wanted a director with a rich cinematic knowledge, which you have. Do you remember when you were first introduced to classic cinema -- was it while growing up in South Africa or later on?

It was bits and bobs. My parents had an interest in the best of American cinema at the time. I have memories of the fact that the Rocky Horror Picture Show was banned in South Africa. My father had it on Betamax, it was buried in our garden, those kinds of things. My work in South Africa is inspired by the fact that I was introduced to the concept of cinema as being something that was transgressive, and that was dangerous, and it was there to provoke an audience. So coming into this, and what it's inspired by, and what it's inspired, I learned that when I went to film school in London. I learned to understand and compartmentalize, who is [Michelangelo] Antonioni, who is [Ingmar] Bergman, who is Michael Haneke, who is [Alfred] Hitchcock. It became more apparent to me as an adult.

The film is set in post-WW2 England, and the original was set in Japan. What do you think you bring to the story itself, being a South African and an ‘outsider’?

I think that it was about lensing -- there was an interest in how I would perceive this period, these people, what my attitude to a British bureaucrat would be. Even Bill's attitude was similar to mine because he was also approaching this man with a curiosity and an interest in exploration. So I think that's always a good thing. When you make a film you need to have something that's sort of strange and different and far away, and Moffie was very much that. I didn't really want to make Moffie, because I didn't think that I could understand the plight of white South African men during apartheid; it felt unnatural to me. And so I learned through Moffie, and even through Skoonheid, that it makes sense to tell stories that require walking in somebody's shoes for a long time.

Your previous films have all been very rooted within South Africa and where you come from, so what was it like to step into a completely different kind of milieu?

Easier than I thought. This is like a gift, like, you're not just getting to make a film outside of South Africa, you're making a film with Bill Nighy, a film with Ishiguro, with [Oscar-winning costume designer] Sandy Powell...I was working with so many amazing people who are operating at a skillset that I've never been exposed to before. I was Charlie in the Chocolate Factory. I was given the golden ticket. It's true -- the difference between making a film in South Africa and a film in London with a different team of people is chalk and cheese. They're so different. I had departments on this movie I've never had before. So it was glorious that way.

But you still brought along South African cinematographer Jamie Ramsey...

Still. Jamie's a big part of my process in the sense of trust, and how we've evolved -- the things we've done apart and the things we've done together, who we are at the moment and who we were 10,12,15 years ago is totally different.

How do you think you have evolved since your first film festival experience with Shirley Adams?

Your first film is without fear, there's no context. You have no idea what you're doing, in the sense that you don't know what the journey is. It's all very exciting. I think now I'm aware of what I do. I'm aware of the fact that my job is to grow. I'm a craftsman, I make something and so my job is to be better at my craft. At the beginning, you're like, 'Oh, this is a knife and this is a piece of wood, maybe I'll carve something,' and now it's about 'What knife? What wood am I using? How can I make this better? What other tools do I need?' It's really a journey on that journey.

In the original Ikiru film, the protagonist dedicates the last months of his life to seeing a park is built. What was it about the story you wanted to keep in Living?

The value of the film, and the value for an audience today, is a moment of self awareness. Today, we live in a world where we don't live in the present -- not just in present time but in present space. We we live on our phones, we live on social media. We live in fantasy, we live in other people's lives that are not necessarily their real lives but what we perceive their life to be, looking at them through the filters. I was interested in the sense that this man comes to a realization that he has to do something very immediate, very present, very tangible, with people in arm's reach, who he knows, and who he realizes he can help. And we don't really do that a lot these days. We might donate things via the internet. We might put our names on things but we, less and less, are rolling up our sleeves and doing things physically and practically, in front of each other, that helps other people.

I think the biggest challenge for me was that all of my previous films have been very dire, in the sense that I've always made work that was kind of accusing the human race of being bad, and accusing us of not understanding ourselves or accusing us of not understanding our past and accusing us of all sorts of things, and Living is a real challenge for me because this is a movie that's meant to inspire people to take a look within, in a good way.

There's that growth you talk about...

It was very hard because I needed to love it, to believe it. As a director, you can't make a film and dial it in. You can't dial in the emotion. You can't dial in the ethos of it. You can't get an actor to do something if you don't know what you feel. So I was thinking, maybe I'll just say that I'm trying to make a film for my parents. Not because they're dying, but because I can finally make a piece of work where they can walk out of the cinema and not be like, 'Wow, that was really scary!'

- The Director and Star of 'The Last Tree' Speak on the Endless ... ›

- Ethiopian Court Drama 'Difret' Heads To U.S. Theaters In Time For ... ›

- 12 Movies That Would Have Passed The 'DuVernay Test' For Racial ... ›

- Sundance Director Sam Soko In Conversation with OkayAfrica ... ›

- South Africa's 'Five Tiger' Selected for 2021 Sundance Film Festival ... ›

- The African Filmmakers Who'll Be Part Of Sundance 2022 - OkayAfrica ›

- The Ebo Sisters On Debuting Their First Feature at Sundance - OkayAfrica ›

- This Malian Filmmaker is Tackling the Stigma of Albinism - OkayAfrica ›

- Ike Nnaebue on Learning to Listen While Making his Personal Documentary ›

- Digitally Restored Version of 'Mapantsula' to Debut at the 2023 Berlin Film Festival ›

- ‘London Recruits’ Tells the True Story of International Anti-Apartheid Solidarity - Okayplayer ›