4 Artists From the New School of Sudanese Music Speak on Their Search for Home & Identity

A sit down conversation with 4 artists from the new school of Sudanese music: Alsarah, Oddisee, Sinkane and Mo Kheir of No Wyld.

Alsarah, Oddisee, Sinkane and Mo Kheir (of No Wyld)are some of the best musicians working and living in New York City. They're also all Sudanese. We got them together for an in-depth conversation about home and identity.

Words by Omnia Saed. Photography by Camilo Fuentealba.

Ahmed Gallab, better known as Sinkane, fans himself from the heat. The walk to the hookah lounge clearly got the best of him.

“We didn’t have an industry to follow, even a skeleton of one," says Gallab about his generation of Sudanese artists.

"You look back on the political and the economic history of Sudan for our generation and at Sharia law and a lot of corrupt governments, all that stuff has silenced entertainment. There aren’t any Sudanese actors, there aren’t any Sudanese musicians. It’s starting to change now.”

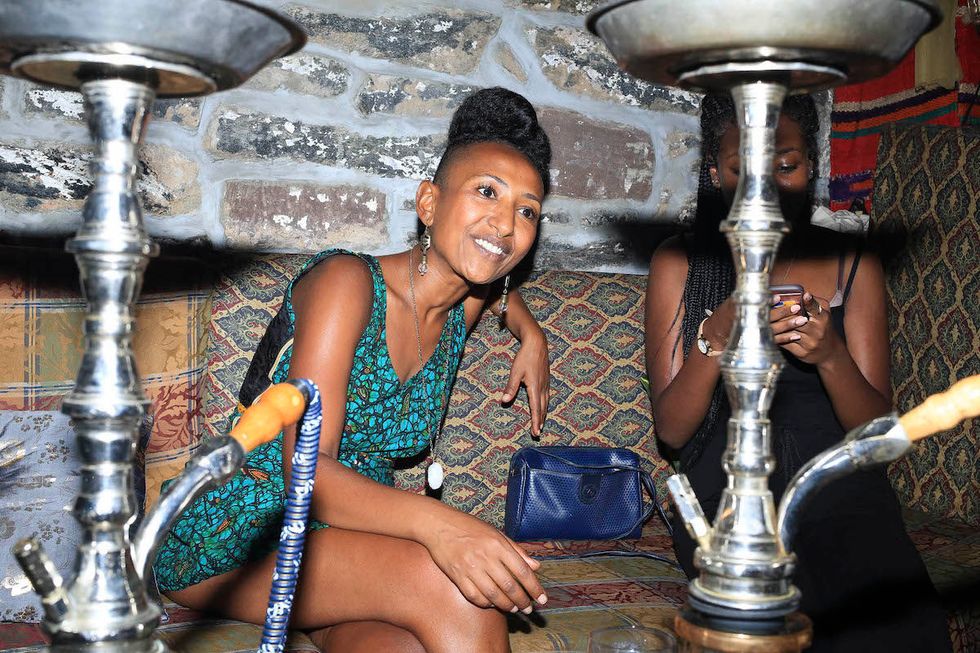

“I’m going to stop you,” Alsarah quickly replies. Having gotten to the restaurant much earlier, she sits poised in her seat, not a gleam of sweat in sight and her hand firmly around a glass of wine.

“There are a lot of Sudanese actors and musicians that have been around. We don’t know about them because of Sudan’s history. In 1981 Nimeiry’s regime actually burned all the archives of Sudanese television.”

She pauses for a bit to think of her next words. It’s the role she’s accustomed to play in a circle of men. The fact checker, the educator and often times the rebuttal, she leans forward and looks at Ahmed directly.

“There’s Aisha Al-Falatiya. It was a big problem for a woman to be a singer at the time, especially because she was coming from a less socioeconomically [advantageous] space, a.k.a. an ethnically different space, which we need to address in the Sudanese community. All these ethnic differences between us that we don’t advocate for influence who’s about to be a public figure and who’s not. There’s been a lot of actors and actresses, but to come from awlad al-3rab (Arab origins) is different then from somewhere else, and it’s important to acknowledge that.”

“Right, right,” concedes Ahmed. “What I’m saying is that they haven’t had a serious opportunity because of the history of Sudan for our generation. One of the things that keeps me going is that I have this opportunity. We all have this opportunity, to make a really big difference to show who we are, to be role models to people and to piggy-back on a lot of the great artists and the great entertainers who didn’t have that opportunity. I think it’s really important to show people that there is a voice for Sudanese people all around the world.”

Wild Child.

We met at the La Sultana, a hookah lounge in New York City's East Village. Finding a Sudanese restaurant in New York proved to be an insurmountable challenge, shisha though, was an agreeable alternative.

Sitting in a chair, scrolling on her phone, Alsarah was seated, legs crossed, 15 minutes early. She was clad in a blue dress, earring dangling from her lobes and an impeccable coif (the type that looks like it would take hours of training to get done, but for her maybe none) her gleaming septum ring greeted me before I reached out my hand. When I did, she smiled.

“I was always a wild kid, and that has always been a source of great strife in my life,” she spoke to me. “I’m close to my Sudanese family, but that closeness is not without a price, you know. My relationship with Sudan is not easy, but the music for me has always been a way to make it easy and make it so that I get to be Sudanese.”

The lead singer for Alsarah & the Nubatones, the thirty-year old artist blends classic traditional 1960s and '70s Nubian anthems with current pop styles.

An Odd Tape.

Amir Mohamed el Khalifa known often times to world as Oddisee, strode in. His droopy eyes framed by his circular glasses fixates on a point whenever he speaks. The popular independent emcee, producer, lyricist and coffee connoisseur has been hailed time and time again as one of the greatest. His album, The Odd Tape, peaked at #12 on iTunes both as an independent project and one solely comprised of instrumentals.

“I use Sudanese time signatures in my music,” he shrugged. “And yet, no one knows its Sudanese time signatures, and yet they like it. It’s different ways of showing it, without pointing a finger.”

Ahmed does it too. It’s keenly heard in his music, like the opening to his song “Jeeper Creeper.” The popular indie musician, who moved to the United States when he was 5, finds his sound in Sudanese pop, in pentatonic and polyrhythmic beats found so keenly in Sudanese songs.

“For me, Sudan is where I came from. Sudan has helped craft my identity, but it’s not the only place. I feel like, as an artist, when you make music you write what you know. And I feel like what I know the most about myself is Sudan, you know,” he says.

Kheif Halak.

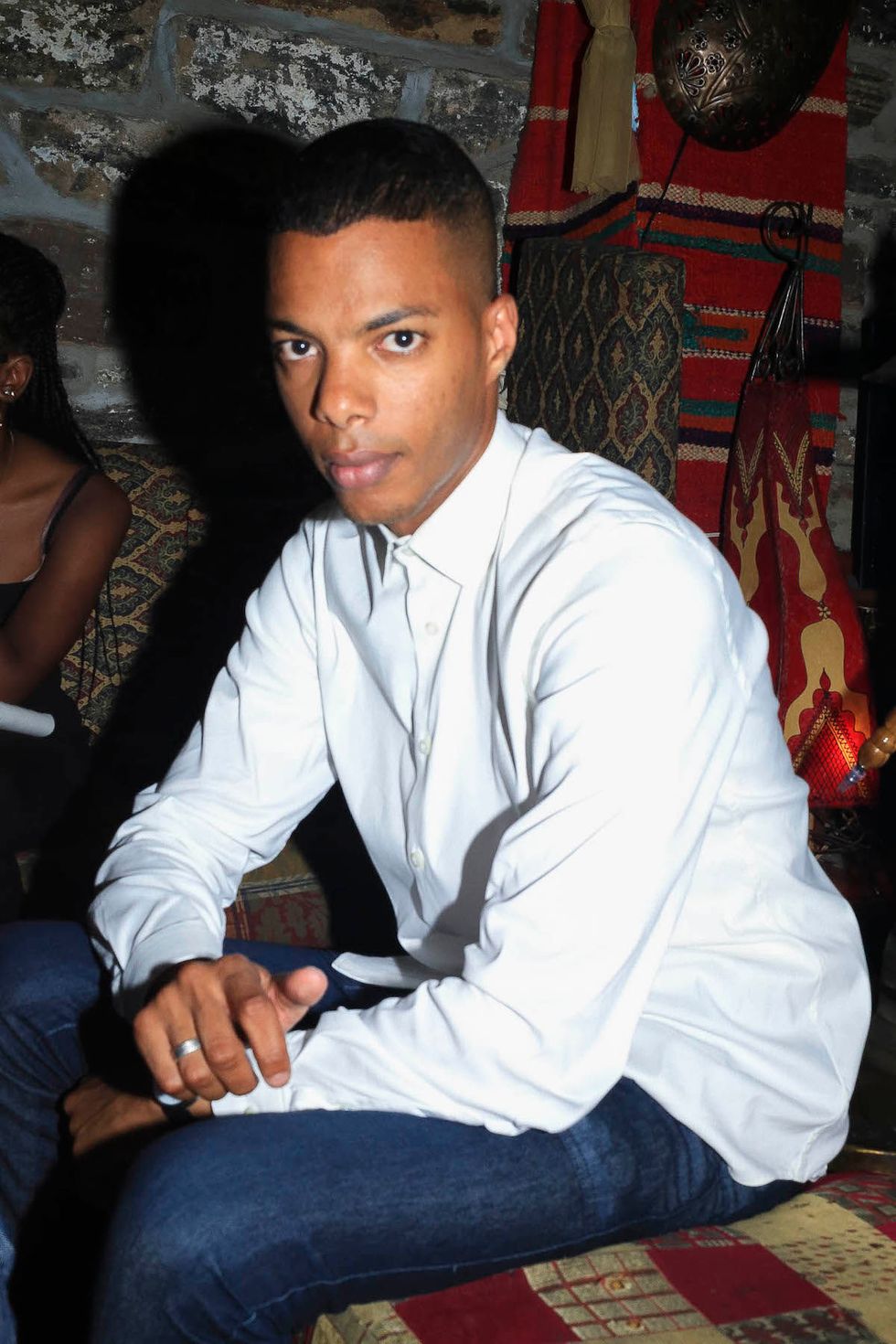

The youngest of the group and maybe even the shyest, Mo Kheir sits down. In a crisp white shirt, so crisp that Ahmed asks in disbelief if he had carried it over on the way so as to not wrinkle it, he laughs to himself. Holding a Masters in Architecture, the New Zealand native is currently the lead vocalist for No Wyld, a group that signed with Columbia Records.

The rest continue to mingle like a group of siblings who haven’t seen each other in a while.

Ahmed goes down the line. “How’s it going bro?” “Sarah, kaif halak.” (Arabic for, ‘how are you.’)

They talk about their tour schedules, sponsorships, rude emails, and family friends they all have in common.

Ahmed explains, “I played in Brussels and I went past the venue and I saw a giant picture of Alsarah’s face on it and it made me so proud that a Sudanese woman was headlining this venue. And Amir and I were going on tour at the same time and at every venue, we’d miss each other by a couple of days.

Amir: “I would see his posters, he would see mine."

Alsarah: “I would see both of y’alls.”

Death to Romance.

Sudan is a thread that holds the group together. It’s apparent in their features, in their Arabic-English language breaks, saying hafla instead of ‘party,’ in the ways that they dress. More importantly, it’s the story that’s found in their music, a story of home and identity, of politicized bodies and song.

“I don’t think of my music as political.” Alsarah explains. “My existence is politicized and so when I commentate on my existence it becomes a political statement, it’s not an on-purpose thing. My body is the crossing of a lot of fucking borders and points, unfortunately to me. I would love to sing a ballad of songs and not deal with shit, I would love that. That sounds fun, that sounds all shiny and full of kittens and then you die and everything is great. I want that world.”

Offspring of Sudan’s 1989’s coup, in which then Col. Omar Hassan al-Bashir overthrew Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi, their stories are also of a home lost. Under the banner of the National Islamic Front, al-Bashir set in motion a country locked in dictatorship, embargoed, de-industrialized, corrupt and stagnant.

“My relationship with Sudan is really painful for me. It’s based on a lot of rejection and my music-making, is sort of my way of making peace with it. My parents left Sudan forcibly,” she says.

The same is said for Ahmed’s parents, Amir’s uncle, and so on.

“I think inherently as children of the second-generation diaspora, everything that we do inherently is political. Our parents were very political and the reason why they left Sudan was very political and that’s a part of our identity. That more or less defines us, you know,” Ahmed says.

Ahmed’s father, Abdullahi Gallab, a journalist and politician, was exiled from the country in 1989.

“My uncle was very political and was exiled as well, and was her next door neighbor in Yemen.” Amir explains pointing to Alsarah. “Both of our families were exiled and they grew up next to each other.”

At it’s heart, it’s grappling with the rejection.

“I go to Khartoum a lot, and I faced the death of my romantic return to home moments a few years ago,” Alsarah says.

Reminiscing

Alsarah notes,“There isn’t a middle class in Sudan. Talking strictly economically.”

Which often gets most people confused because, “in Sudan we’re still confusing who your family, what your ethnic status is, with actually being able to succeed or not,” Ahmed explains.

“Democracy meets tribalism,” adds Amir.

“It’s really a big conversation about post-colonial Africa, what happened after all the colonists left and how they left the country to the indigenous people and what they did with it. When we talk to our parents about what Sudan was like in the '70s or the '60s. They say it was beautiful, there were shops everywhere, we went to the movies, we would go out and drink with our friends and this and whatever. And that wasn’t a Sudanese infrastructure, that was a colonial infrastructure. That was created by the French, the British, the Dutch,” Ahmed adds on.

Listing off all the resources in the country (the oil, horticulture, sunlight, cotton, leather) he adds, “We have the power to make it work.”

They all nod their heads in unison.

Tracing History.

“I spend my time in Sudan diving into the history constantly, because there’s one side of my identity that’s completely deprived of it and I’m forever grateful for it,” Amir says.

“Sudan is an anchor for me. My mother is black American, my father is Sudanese. I was raised by my step-mother and my father who were both Sudanese, and to come from a culture where I knew that there’s one side of my family where I can’t know my history, made me appreciate the side where I could trace my history.”

It’s About Sexism, Son

“I’m only Sudanese because my father is Sudanese, if my mother was forget it. Culturally and politically, the Sudanese community only accepts me here and in Sudan, which has been an issue with me growing up my entire life, that I’m only accepted because my father is Sudanese.”

Amir holds the shisha pipe in one hand and looks at the eyes on him.

Alsarah quickly cuts in. “This is about sexism son. This isn’t about being Sudani or anything else, this is straight up sexism.” Alsarah who is from the Dongola and the Galiya regions of Sudan scathes. “I am by blood equal, but grew up Dongolowiya. But I can’t identify [as it], because we grew up in a sexist society. It’s that simple.” In other words, because her father is Galiya, so is she.

It’s Complicated.

Lounging around now more comfortably, the small talk fades away and the greetings have left the air. The only form of movement stems from who gets a drag of the hookah next, except Amir who proclaimed quite early “I’m going to get my own,” so he doesn’t have to share.

“I don’t really feel like I had a home because I moved around a lot growing up,” says Mo. It’s an inherent immigrant mentality that finds home in the conversation.

“I’m not from anywhere. I’m a nomad,” he says affirmingly. His upcoming album with No Wyld, in honor to reality will be called Nomads.

And to be nomads is to try to conceive of an identity that picks up and leaves, that travels along with your bags.

The Sudanese first-generation dilemma, it seems in uncovering the question of who you are and who you want to be the emptier the answer becomes. Are we Arab, are we black, are we African, are we Sudanese, are we American, are we home? Place these questions under a spotlight and a growing music career, music is left to fill the void.

“I’ve been an immigrant my whole life and I identify more actually as an immigrant than I do anything else. I was born Sudanese and I die Sudanese and in between is an immigrant path,” Alsarah explains.

Living dual lives as both foreigners and natives at home and abroad, a new school of Sudanese immigrants come about.

“I’ve learned to live in that duality,” Amir explains. “And speak in that duality and not judge [my parents] because I know what they are. I come from what they are. I visit from where they are, but they have never seen or can fathom what I am and I can’t hold that against them and I feel like a lot of first generation kids struggle with that.”

And so, “I have the mentality of an immigrant in my own country that I was born and raised in. I’m super thankful for it. I don’t undervalue anything. I am content with nothing and appreciative of everything as a result of first-hand witnessing having nothing for real.”

The Foreigner & The Native.

“Just as much as we are Sudanese, we’re not Sudanese. There’s a whole other part of our identity that’s not Sudanese,” Ahmed looks to the group and says.

There’s a disconnect.

“We don’t really know what Sudanese people like. In Khartoum, we don’t know what the pop culture hits are,” Alsarah explains.

So when going back, it’s a question of uncovering privilege, foreignity and that very same disconnection.

Posing the question to the group. Amir wonders, “Every once in awhile I ask, how are we no different from the foreigner who reaps the benefit of coming outside. Are we different?”

To which Alsarah replies, “We’re no different if we also decide not to learn anything, decide we’re better than everybody and decide to never engage and build in from the outside and leave. If we do that, then no, we’re not any different than that person, you’re right. But if you go home to set up home, that’s different. You’re trying to create a space for yourself to exist there and you’re giving something. You have to do it on the ground, with people from the ground.”

She sips some wine before finally saying, “You have to commit to Sudan.”When I asked, if anyone would I was met with silence, shaking of heads and mostly no’s.

“I think the best thing we can do is inspire.” Ahmed then says. I think there are a lot of young people in Sudan, who are very creative and who are very hungry and who are very smart that are stuck and just don’t know what to do. They have all these great ideas for business, for politics, for many different things. They don’t know what to do, because what they see around them isn’t that inspiring but, if the only thing I can do is hear from some young person in Sudan ‘Hey, listen I really have this great idea and when I saw you doing your thing it inspired me to do my own’ that means the world to me. And I think that’s the best way we can do it. Going back to Sudan and investing is something we can do, but that’s a foreign concept.”

It’s important to remember that “we have the privilege to choose which parts of Sudanese identity we want and discard the other ones without obligation. Losing that obligation comes with great adversity. And that’s the one thing we might all have in common is that adversity you face when you decide to go against the norm,” Amir explains.

Rakshas + Rihanna

“I’ve only be accepted as Sudanese when my success was visible by Sudanese.”

And it’s that same fear that pervades in headlining a show in Sudan, Oddisee explains.

“They would come out to see the American rapper, not my music”

Alsarah: “No.” I think you’re looking at it from a narrow way.”

Amir: “Talk to me.”

Alsarah: “Most Sudanese people don’t listen to rap period, because they don’t speak English, end of story. It’s really simple.”

“But they do. If I’m riding around a raksha [motor carts], what are they playing? I’m hearing Rihanna, I’m hearing Drake.”

“But they don’t actually understand the words. You’re rapping at them at a way faster rate of English than they would be able to comprehend. It takes months for a raksha driver to dissect a Rihanna song, between him and his buddies.”

“The people in Sudan, asking you to come for a show are already hip-hop heads, they listen to hip-hop regardless of its nationality. They are reaching out to you, not only because they like your artwork but because they like hip-hop and also because you’re Sudanese as well. They’re like, ‘Shit, that might be possible to do.’”

Amir: “I’m too hype- conscious of myself and my identity, of where I am and who I am to do it”

Ahmed: “When they see you, they’re like ‘he’s one of us’ You have to open the door in order for them to really understand what you’re saying.

Mo Kheir: “You open a new market though, a new state of mind.

You Raised Us Up.

As the coals burn out atop the hookahs, the music growing a bit louder from the Friday night buzz, Ahmed tells the group.

“After a show, a group of Sudanese people came up and said to me, ‘inta rafata Sudan fowg’ (‘you raised Sudan up’), and that’s all I need.”

He’s met with nods in agreement.

“And I don’t care if they don’t understand what I’m saying, someone up on a stage, up high who they walk by this place every weekend and they see other non-Sudanese people and they finally see a Sudanese person. That’s inspiring, that’s amazing, that’s the best you can do.”

But more so than that, it’s about just being human.

“I want to show Sudanese people, Black Americans and Muslim people that you can be human first and all of those things second,” Amir says.

So “that you can live your life, however you want to live your life,” Ahmed adds on. You don’t have to live it the way they ingrained it in you in Sudan. You can be an artist if you want to be an artist. You can be a graphic designer, if you want to be a graphic designer. You can do whatever you want. The power is in you. It’s important to believe in yourself. If they can see a person like me, or a person like Alsarah, specifically Alsarah because she’s a woman and because in Sudan it’s hard. There’s a huge double standard.”

“In America too,” someone quickly replies.

Alsarah who has gotten quieter now, listening to her male counterparts, looks blankly at the group and says “For me it’s always been a question of realizing what Sudan really is.”Everyone is listening.

“Sudan has over 48 different languages with different cultures and ethnicities in it. So Sudan’s culture is not based on same, it’s based on difference, so all I want to do is bring that back up to the surface again and not change Sudan, but just make room for someone like me in Sudan. I don’t even need Sudanese people to like me, I just need them to respect my existence to give me enough space so that maybe the next person after can be liked. I don’t need to be liked, I just need to be respected so no one is trying to shoot me while I’m on stage, no one is trying to shut down my show while I’m on stage. And no one is trying to troll me on the internet like they do all fucking day, so I can have an existence as a human being, making art first as a person, without needing to discuss my vagina first. I just want to make that happen, if that happens I would be so happy. I don’t need any change, just space. I just want space.”

And ever so quietly, she murmured, “To exist is to resist.”

It’s a reminder to the room of the journeys they’ve taken. A medley of songs and identities, politics and family, sitting casually in a lounge in the middle of New York city, miles away from houses that were at one point meant to be homes, customs and cultures to which they no longer claim, a language which visits as often as a cousin abroad, they are the skeleton, whether they embrace it or not.

“My father has never heard a song I’ve done. He’s never been to a show, and he’s never heard a record. We don’t talk about my music. We talk about ‘How’s business,'” Amir says.

They are fluent in many tongues, including the ones to which they speak with their parents to, their families back home, their aunts and uncles. They often times fight against the mold. “Life has no room for oppression,” Alsarah says as I look at her hair coif, earrings and blue dress in a different light.

“In Sudan we tell stories. It legitimizes. You see me on David Letterman. The moment I told my mom I was playing on David Letterman it changed everything and all she did was show people. She’s like ‘look he’s doing something,” Ahmed adds.

Lounging around, laughing with one another, smiling at each other they bond over more than just their country of origin, but of their journeys and of who they are. They are untold stories of hundreds of immigrants, of first-generation Sudanese children, of homes lost and reclaimed, and of the future. The new school of Sudanese music, culture and art, the new school for Sudan.

Ahmed finally looks up and says a point he’s been trying to make for a while now. “It’s up to us, to keep doing what we do as sincerely as possible to make sure that those other people that are like us can say Alsarah is doing it, or Ahmed is doing it, or Mohamed is doing it or Amir is doing it, I can feel confident and not feel crazy too.”

- This Album Is a Soundtrack of Sudan’s Revolution - OkayAfrica ›

- A Year Into the War, Sudanese Artists are Building Communities of Care in Nairobi - Okayplayer ›

- Nadine El Roubi is at Her Most Confident and Vulnerable in ‘Freestyles Pt. 2 Mixtape’ - Okayplayer ›

- Is the Rise of Sudanese Rap Breaking Down Racist Stereotypes? - Okayplayer ›

- “It’s a beautiful struggle“: Lessons from Sudanese Community Organizers - Okayplayer ›

- Emmanuel Jal Wants His People to Shower With Milk | OkayAfrica ›