In ‘Borders Between Us’ Poet Saidu Tejan-Thomas Embarks on a Journey to Rediscover His Mother's Life

In his new audio essay the Sierra Leonean poet and storyteller shares a deeply personal, yet relatable, tale of familial relationships, sacrifice and forgiveness.

Saidu Tejan-Thomas first began writing poetry while pursuing a public relations degree at the Virginia Commonwealth University. While he soon discovered that PR wasn't the career path for him, he also discovered that poetry and writing were a meaningful outlet for his passion for storytelling. An interest in podcasting and audio work developed soon after. In his newly published audio essay, Borders Between Us, the accomplished poet fuses this talent for spoken word, writing, and auditory storytelling to take listeners on a personal journey of family, migration and forgiveness.

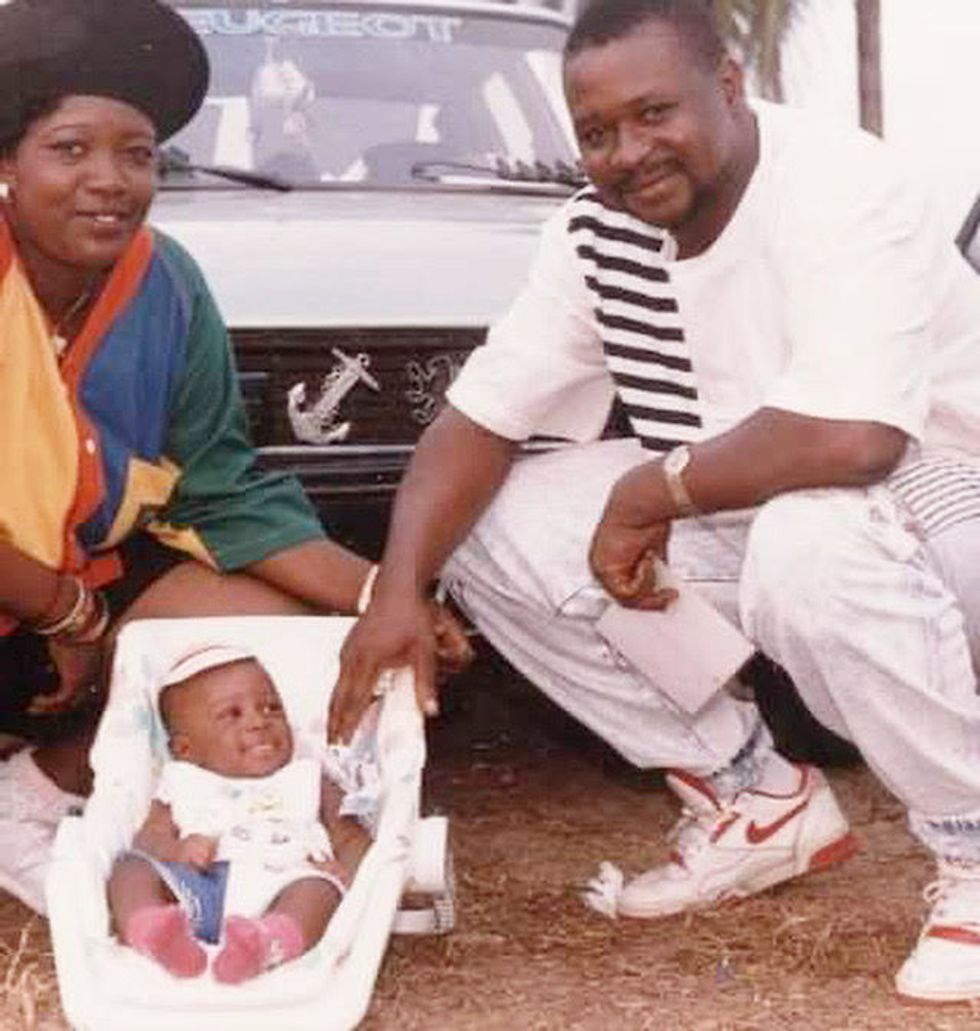

Born in Sierra Leone, Tejan-Thomas moved to Alexandria, Virginia in middle school to live with his mother, who had immigrated there shortly after his birth. This began a process of learning and unlearning his mother's story and the complex intergenerational dynamics that shaped their relationship. In the Borders Between Us, the writer shares detailed memories from his childhood, introspective observations about identity, and an enlightening conversation with his aunt that brings him close to understanding who his mother was as a person. It's a journey that many of us take on a deeply personal level, but one that some might be hesitant to share. Tejan-Thomas, instead, shares his journey openly and honestly.

OkayAfrica recently spoke with Tejan-Thomas about his latest audio work, which he described as "an essay and a poem all in one." Read our conversation below and listen to the Borders Between Us via the public radio platform Transom.org.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity

What led you to want to create and share this story?

This year I took a trip to Sierra Leone. It was my first time going to Sierra Leone in 10 years [and I was seeing it] through my adult eyes, so I took a recorder with me. I recorded a bunch of stuff, and I wanted to do this big piece about going back home for the first time in a long time. But, it was too big, and sprawling, and didn't have any focus, so when I got back from my trip, I was going over stuff I had written and I was like, "Damn, this is trash. This is not good." That's what you hear at the top of the show. The top of the episode was me being like, "This is not good."

Then I tried to figure out what it was. What did I really learn from this trip? It turns out I really didn't learn much, but what it did was raise a lot of questions about my mom, and the relationship I had with her. I had gone to visit her grave, so I had some tape of me being at her grave. I reached out to Transom.org, and shared the idea for this story, gave them a bit of background information about me and my mom, and they were immediately onboard. They helped me develop this, and we worked together. The piece is a realization of a thought that I had when I was going into public radio, or podcasting, which was: I want to do that but in my own voice. It took me four and a half years, but I finally got to do it. I'm so grateful for that.

When was the point where you came to understand the sacrifices that your mom made rather than being angry towards her when she didn't seem present?

I think that happened at a very early age. I've always known, and also African parents don't let you forget. They do not let you forget that they walked 50 miles to school every day. They don't let you forget that they brought you to this country. They threaten to send you back multiple times, get your shit together. They don't let you forget that they made sacrifices for you. We know that. I think I resented it, but at the same time, I respected it because I was like, "Damn, they're right. This shit's real. The shit that they do is real." It's those two opposing things that bang up against each other, where you resent the pressure, but you also appreciate it. You also appreciate the mantle that you've been given. You appreciate that responsibility. You're like, "Damn, I want to be the person who helps my family. I want to be the person who gets them out of the struggle." At the same time you secretly resent it. It's that conflict that made it hard for me to ever talk about this thing with my mom, this tough relationship that we had because I both appreciated it, and I resented it.

I knew it for a long time, but the thing about it is that when your parents tell you all the things that they sacrificed for you sometimes it's very vague, and you just fill in the blanks about what they mean when they say that they gave up a lot. You don't exactly know all the things. The moment when I really knew the things and could feel them, was when I talked to my aunt this year for the story. She told me what my mom's life was like before me. My mom and I didn't have a relationship where she told me stuff about herself growing up. I would sometimes hear stuff from her sisters here and there. This was another one of those moments where my aunt just laid out her life for me, and I was like, "Oh damn, she was doing her thing. She was having a whole life. She really took on all that for me and our family." I would say I've always had an idea, but those ideas became more concrete this year.

What would you say you learnt about yourself through this process of learning more about your mother? WHat's been most eye-opening?

It illuminated a few things. I think it taught me about how the situation that me and my mother were in—and maybe a lot of people and their parents are in—are just not our fault. Shit just happens. The way the immigration system was set up was such that I couldn't come be with her here at the same time that she was coming here. My dad couldn't come. We were always separated from each other at different points. It just made clear to me the cost of being separate from your family in order to gain citizenship in America, which is distance. The cost is sacrifice. The cost is feeling like you're never quite close to somebody. The cost is always feeling like you're catching up, or trying to catch up, or trying to make up, or trying to prove something to somebody. You're always trying to close that distance with that person.

Personally, it taught me a lot about my mom. It made her a full person—a full human outside of me. Weirdly enough, it made me appreciate her even more. It put words to her silence. She didn't talk a lot, but talking to her sisters, and people who are talking for her—it [filled in] all those moments where she couldn't say what she wanted to say, or maybe didn't have the right words, or was too tired. It filled in all those blanks, because what happens when you have silence is you just start making shit up in your head. You just start thinking, "Oh, maybe this person doesn't like me. Maybe this person resents me in some way." In actuality it's like, no, they love you. They're just stressed, or they're just tired. They just don't have the right words, and they've never been able to learn the right words because now they've got to go to work. My closest friends, a lot of them have tough relationships with their mothers and fathers. I don't think it's the same case for everybody, but we never know what the fuck's going on with our parents. This allowed me to really look deeper into that, and flesh out some of the reasoning behind why she was being the way she was. That made me feel happier about our relationship.

I also really appreciate that you touched on grief, like with the passing of your parents. You also touched on some of the past trouble you faced while in school. Was that hard for you to revisit that, especially in such an open forum that you're sharing with the world?

I wouldn't say it was hard—it was vulnerable, and any time you're vulnerable you feel like you're putting shit on the line. You're just putting yourself on the line for people to pick apart, and comment, and criticize. I don't think that part will ever get easy. When you put yourself out there it's just going to be there. It's there for people to do with what they will. I made my peace with that because this isn't the first time that I've written something personal about my life. It's hard for me to write any other way, but at least for my personal self it's hard for me to write in a way that's not vulnerable, and not honest, and not fully just exploring as many corners of the thing as possible.

I've done a piece that was very personal before. It was a poem called Play. That was my first introduction into putting myself out there. People still hit me up today about how that piece has helped them. It's just a poem. It's not a regular story. I don't even think I necessarily do it for people to tell me that the piece helped them, or anything like that. I do it because I just feel like I have to. There's just something in me that's like, "There's a story that you have to tell."

"It just made clear to me the cost of being separate from your family in order to gain citizenship in America, which is distance. The cost is sacrifice. The cost is feeling like you're never quite close to somebody."

Something that you said towards the end of the story was "I felt responsible for something." You were talking to your aunt about some of the guilt you felt about your mom. I feel like that's a common feeling amongst immigrant children to just feel guilty all the time for some of the hardships our parents face. Why do you think that we bear that weight a lot of the time?

The responsibility that we feel, comes from our dedication and loyalty to our parents through and through. It's funny because I think even if you have a bad relationship with your parents, at least the African kids, if you came up you would still want to pull up in a Benz for your mom. You would still want to buy her a house. You still want to get her to stop working that nursing home job. You know what I'm saying? There's just this inherent drive within us that we learn pretty young that we are in some ways "the last hope." I think it maybe goes back to this idea of us always having known that our parents have sacrificed, and I think in some way we want to be able to reciprocate that for our parents. We want to be able to give them financial freedom, or material gain—what they gave to us by sacrificing their own personal lives, their home and their future. We know what they've poured into us, and we want to pour it equally back into them.

Can you talk a bit about closure and if you think you've gained it through this process?

Closure is one of those things that if no one had ever mentioned it, I wouldn't consider it. It's that thing that has been introduced. Therefore, it feels like you have to consider it, and you have to figure out whether you need it or not, but I don't think I think too much about closure. I think a lot more about whether or not I'm at peace. Before this piece I didn't feel like I was at peace, and now I do. Now I feel like it's something that I have addressed, and it's a thing I will live with—and will continue to live with—but I don't feel like I'm wrestling with it anymore. It doesn't feel like there's a disturbance in me anymore. It just feels like, "Oh, whatever that disturbance was I faced it. I've addressed it, and now I just feel more peaceful."

***

Listen to Borders Between Us in full on Transom.org.