Afrofuturism Inspired One of Miami’s Hottest Art Fairs

We speak with Mikhaile Solomon, founder and director of Prizm Art Fair of African and Diasporan artists during Miami Art Week.

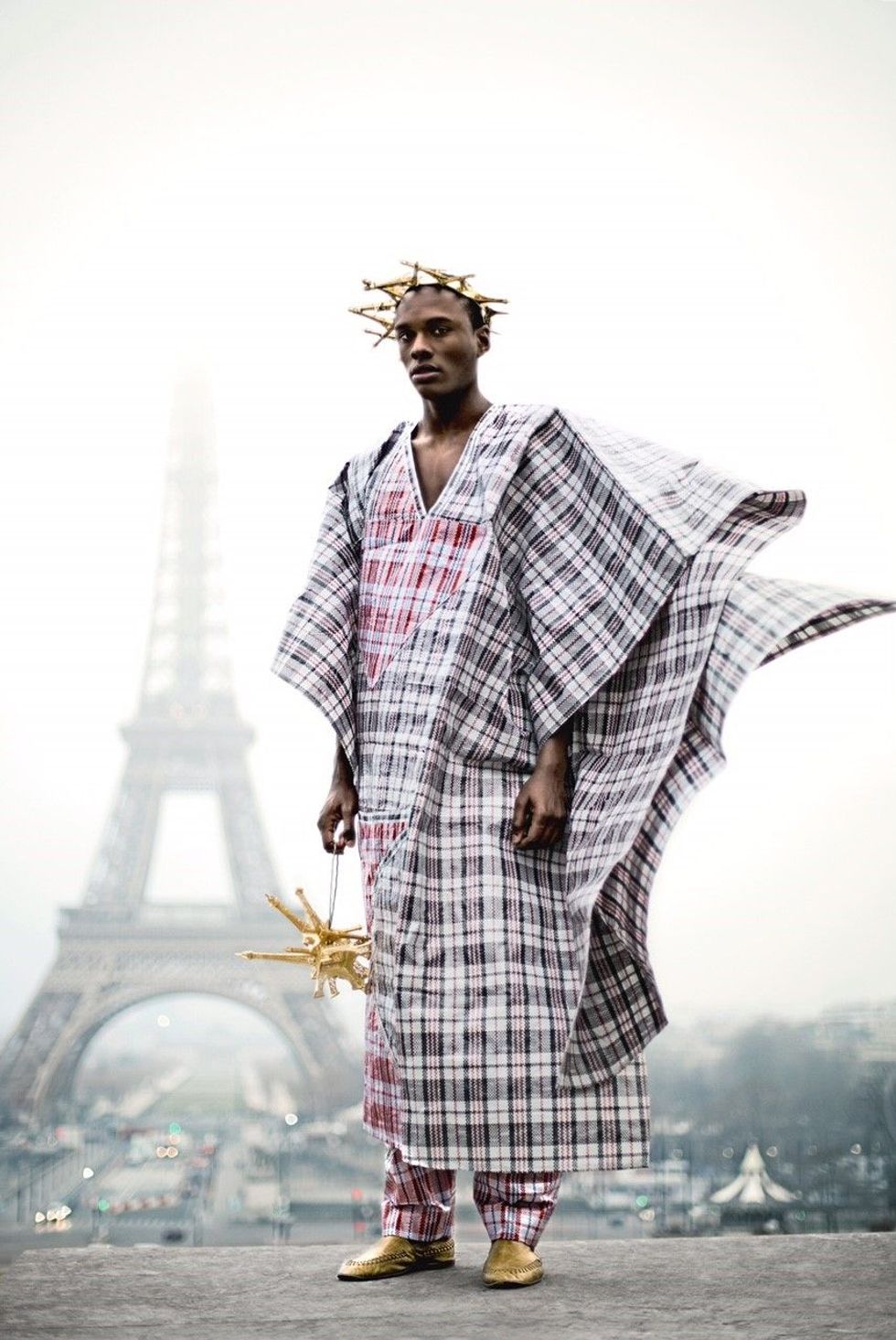

Miami Art Week is here again. And while upwards of 70,000 art-fiends will flock to the main attraction at the Miami Beach Convention Center, Little Haiti/Little River is the true epicenter of afrofuturism.

Now in its fourth year, Prizm Art Fair is continuing to shine a much-needed spotlight on emerging artists from the African Continent and Diaspora. Held over the course of two weeks in December, this year’s edition will explore the global impact of Africa’s cultural DNA (Prizm’s 2016 theme) through the work of more than 55 artists representing eight countries total. And unlike most art fairs, it’s the artists themselves (read: not gallerists) who exhibit their own work.

“The fair,” a statement reads, “aims to give a voice to those often not represented in the mainstream art world.”

It will do so in a bigger space than it’s done in the past—Prizm’s latest home is a full 3,000-square-feet larger than its previous location. (Held in the Miami Modern District in 2015 and at the Miami Center for Architecture and Design prior to that, the fair rotates locations each year.)

We caught up with Prizm's founder and director, Mikhaile Solomon, ahead of this week's art happenings. In the phone conversation below, the Miami native shares how afrofuturism inspired one of the city's hottest art fairs and what she's personally looking forward to at the 2016 Prizm Art Fair.

How did Prizm get started?

I started the fair back in 2013. I was obsessed with afrofuturism. If you want to really define it in a very rudimentary way, it's sort of like the collision between science fiction and cosmology and black culture. I've always been really interested in comic books and deifying black icons. And so when I was thinking about the art fair, I was like “It would be kind of cool if I created a whole entire art fair that would just focus on this afrofuturism concept.” But then I realized that would put me into a really small niche. [And so] I used the idea as a vehicle for the actual branding of the fair.

The idea behind the art fair came from my fascination with afrofuturism. But then it became a broader art fair to encapsulate everything that is African Diaspora contemporary art.

A part of the reason why I did it was the idea that I wasn't seeing a lot of Diaspora-focused artwork in a lot of the main spaces like Basel and Frieze and Armory. I know Armory this year did a focus on Africa with Contemporary And—these are sort of recent inclusions that I think are great. I hope that it's not just a trend, that it's a continued conversation that endures.

What’s your take on African and Diasporan art and artists in the Miami art space?

After I started meeting a lot of my [visual artist] friends, people that I call friends now, I realized that there weren’t enough spaces or platforms during things like Basel. These are folks that weren’t showing in larger, more established spaces during Basel.

Basel would come to Miami, and artists like Robert McKnight, T. Eliott Mansa and Bayunga Kialeuka, for instance, these are all names that everybody locally knows, but in the broader international conversation around Diasporic work, they're not really well known. That's why initiatives like Prizm are important, to help elevate the voices of people who have consistently been working and producing work in the Miami landscape for years, and are well known locally, but the work has to extend beyond our borders so people can have access to their content as well.

Why Little Haiti this year?

The crassest answer is it was available. On top of that, Little Haiti is also a very culturally rich space. A lot of artists that are in the show grew up in Little Haiti, and their studios are here in Little Haiti. It was a space that became available, but I was like, "this is very appropriate because of the work that we're showing."

For instance, in our Perform section this year, we’re working with an artist named Nyugen Smith. He's based in New Jersey, but he's of Haitian and Trinidadian descent. He's producing a whole entire performance around the evolution of his lineage. There's going to be himself, who kind of represents the present, an elder in the community and someone that's younger than him. It's sort of an intergenerational conversation about his own personal lineage. For him it's an important piece because he unfortunately did not learn a lot about his heritage growing up. The piece is actually process for him in terms of him getting closer to understanding his whole entire ethnic experience.

What else are you looking forward to at the fair?

We're hosting two dinner events. One that's kind of an early preview of the fair. Then we'll also be showing a video installation by Allison Janae Hamilton, which is called In the Land of Milk or Honey. There will be a long family-style dinner table with two chefs, Jamila Ross and Akino West, who are based in Miami.

We're also doing an event on the Miami Science Barge, which is an experimental space that's located right off the dock of Biscayne Bay. We're hosting it in collaboration with a group called Famous Art Critics where we dine and we dialogue about pathways to cultural equity, about making art institutions more inclusive.

Our public opening day, which is December 1st, we always have a fun day where we have a DJ in the space. People can come and feel really familial. People can enjoy themselves while they look at the art. And December 1st is when we're having our performances. Nyugen’s project with his family will be at 6pm.

Another young lady from New York, Ayana Evans, she's doing a piece called Gurl I'll Drink Your Bath Water. If you know anything about that saying, it's a southern saying, almost like a cat call. It means you’re so gorgeous that I would degrade myself enough to go ahead and drink the water that you bathed in.

She's doing a whole performance that is multi-layered. She's essentially bathing herself, removing things that have a lot of spiritual undertones, a lot of religious undertones. There's a layer of feminism. There’s a layer of nostalgia for herself, personally, because she's washing herself with Palmolive soap detergent, because that's a detergent that her grandmother used consistently when she was growing up. The smell of it, the color of it, it's all very nostalgic for her.

It's a performance piece that's both autobiographical and social commentary. For me it was very gut-wrenching when I watched it. I'm interested to see how people respond to it. I hope people will have a lot of questions.

Prizm takes place November 29 through December 11, 2016 at 7230 NW Miami CT in the Little Haiti / Little River community.

This interview has been edited and condensed.