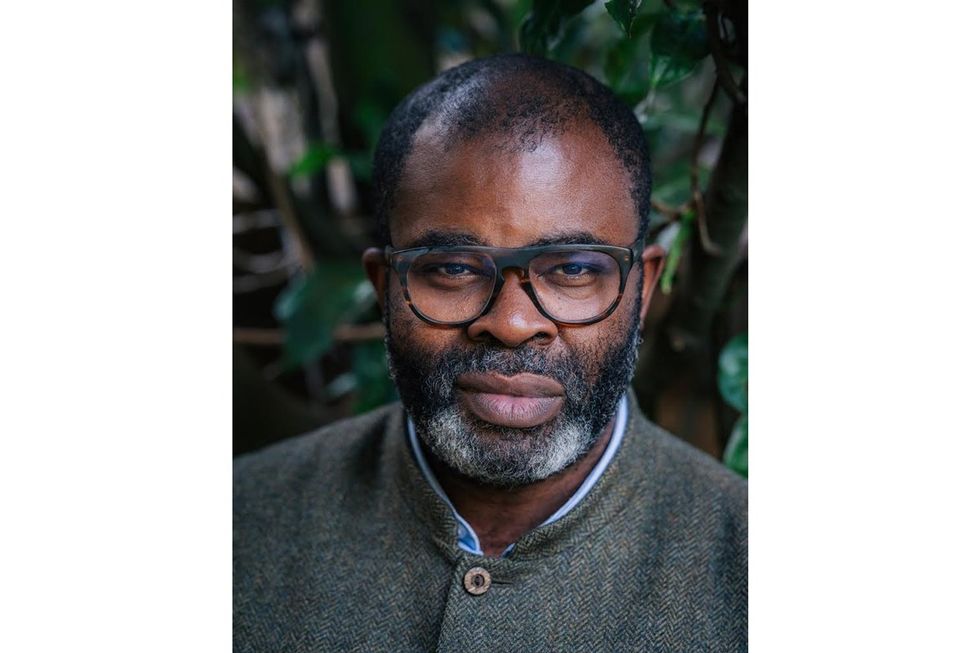

Oscar-Nominated Director Misan Harriman on The Story Behind 'The After'

Nigeria-born photographer Misan Harriman discusses his creative connection with actor David Oyelowo, making a pivot into filmmaking and his passion for activism.

A still image of David Oyelowo from 'The After.'

The opening of The After, the Oscar-nominated short film directed by Misan Harriman and starring David Oyelowo, is filled with implied trepidation. At first, it is unclear what tragedy is on the way, but the feeling that something catastrophic is about to happen hangs stiff and sure in the air as Oyelowo’s character, Dayo, spends a sunny, lighthearted day with his family. When the tragedy happens — a public act of violence that claims the life of Dayo’s wife and daughter — it is short but explosive. The aftermath of the event is harrowing, made more so by Oyelowo’s uncontainable, yet deeply felt despair. It’s a scene that is powerful for its rawness, as well as the masterful camerawork that tactfully focuses on Dayo’s maddening grief, before zooming out slowly, as if to give him space to collect himself.

As Harriman tells OkayAfrica, Oyelowo drew from the grief of losing his parents while filming the short. “There's so much you see there that is unplanned, that is just coming out of David,” he says. “We made sure that the lens was in the right place and that he felt safe enough.” The rest of the film follows Dayo, who becomes a ride-share driver in a bid to minimize human contact, but is moved by a passenger to finally confront his grief.

The After is a first foray into filmmaking for the Nigerian-born, British photographer and activist Harriman. Famous for his celebrity portraitures, having photographed stars like Rihanna, Megan Markle and Prince Harry, he became even more known as the first Black person to shoot the cover for British Vogue’s September Issue, the magazine’s biggest issue. During the Black Lives Matter protests, his photographs of protesters captivated the world, including British Vogue former editor-in-chief Edward Eninful, and Oyelowo, who found his work deeply affecting.

The film has already been well received, nabbing an Oscar nomination in the short film category, while exploring a heavy subject like grief with nuance and gentleness.

Ahead of the Academy Award ceremony this Sunday, OkayAfrica spoke to Harriman about venturing into filmmaking, and the liberating power of grief.

OkayAfrica: Ahead of the Oscars, how are you feeling about being nominated?

Misan Harriman: I'm very humbled and very excited… This film has taken me on a life-changing journey that I never expected. To be chosen by the Academy as an Oscar-nominated film is something that doesn't happen in two lifetimes for many people. So to have it happen for my first film is a blessing.

Did you have any concerns before you decided to make this leap into filmmaking?

Of course. I speak a lot about my challenges with anxiety and self-doubt. They're always with me. I have no formal training as a filmmaker, just like I have no formal training as a photographer, but the opportunity came and my whole life I've been obsessed with film but from the outside looking in.

And it is in those moments of self-doubt you can carve the greatest version of who you were always supposed to be. So I took a big step into the unknown with some great collaborators. The quality of work and the honesty of your work hasn't got any age limits.

What propelled the conviction that you had to make The After?

I had a really rough 2020, and when I think about the mental health challenges of George Floyd, of COVID, of the world going upside down, I think, my God, in the next five years, people are still gonna be dealing with the mental [strain]. I work a lot in humanitarian aid and mental health awareness and people are really struggling right now, so I needed to try and make something that will let them know that it's possible to be broken and it's possible to build yourself back up after that.

A striking quality about the directorial eye in The After is its sensitivity towards capturing the randomness of grief – what went into making that possible?

David had lost both his mother and father before we came to collaborate together. He is still grieving, and he certainly was still grieving then. So my job, as a director, was to make sure he had a space to express that in any way that he chose to because sometimes, it's not so much about how much you follow the script, it's about how much you understand the ability of the lens’ observation. This is also the first time a Naija man has directed him. And that meant a lot to me and him. There was a real sense of safety for both of us to take this film to places that people don't always go to.

Something The After portrays quite well is how life simply continues, no matter the monumental tragedies people experience. Where or what did you draw from when developing that feeling on screen?

Well, it's just my own experience and David's, you know, and so many other people we spoke to. When you're really struggling, it's usually the mundane moments in life when people are just getting on with their own situation, that grief can knock the wind out of your sails. You can be on a lunch break in the office and suddenly you need to go and sit in the toilet and just lie on the floor. There are aspects of Nigerian culture, where it can be very hard to fully express yourself when you're struggling with something emotional and we have to get better with that. We have to make space for mental health care.

Connecting this to how Black men are portrayed on screen when expressing grief, The After truly allows Dayo to be at his most vulnerable without being shunned. Was this a point you set out to make?

I think everything I do, there's intent whether I realize it or not. And as a Black man there's so much that is from my own lived experience in any of the stories that I look to tell. I wanted to afford us grace in our own vulnerability, in our own pain. The Black man and the Black woman have had to be strong for too long, and there is something to be said for not having to carry that weight.

And when that weight makes you buckle, there's also something to be said for that being proof that you are a human being. Not less than, not a failure, not a fool, you are a human being. And you should be given the space to dust yourself off and figure out how to go on a journey of self-love and growth. In fact, that is a kind of strength that we need to appreciate. I've been in screenings with predominantly Black people in the room, Black men inside the cinema weeping. You know they needed that release.

Amazing. What was the best part of making this film for you?

The best part was David and I having this unspoken connection; it was as if our souls knew each other from another life. It was as if our forefathers had planned this symphony, this union of creativity. There were times when I would just look at him and our eyes would catch, and he knew what he had to do. And I knew where I had to put the lens. I knew how to give him the space for him to do such an extraordinary performance – one of the greatest acting performances of our time in my opinion, by this Naija man.

Activism is important to you – how do you balance it with your artistic practice?

I'm not someone that's going to be willfully ignorant to a world that's seemingly on fire. I'm not someone that cares more about fame than integrity. I'm not someone that's going to see children suffering, particularly children suffering, and be more interested in clout. Maybe it's because a lot of what's happened to me is in later life. And I've seen enough of the world to know what matters.

And also I'm a father of two little girls. What I think daily about the world they're going to inherit as young women. And it ain't the world that I'm living through today. I have to do everything in my power to make sure that there's light in their future. So I think it's a combination of all of those things.

You’re working on a new documentary for Paramount Plus – what else can we look forward to from you?

I have loads of photography going on at any given moment so that's never going to stop. I am also shooting multiple big campaigns that will be announced when the time is right. I'm also working on my first major exhibition. In due course, I hope to be able to take on my first feature film. But for now, if you factor in I'm the chairman of Europe's largest multi-art center, the South Bank Centre [in London], on top of all of the work I do with Save the Children and Choose Love, my plate is pretty full.