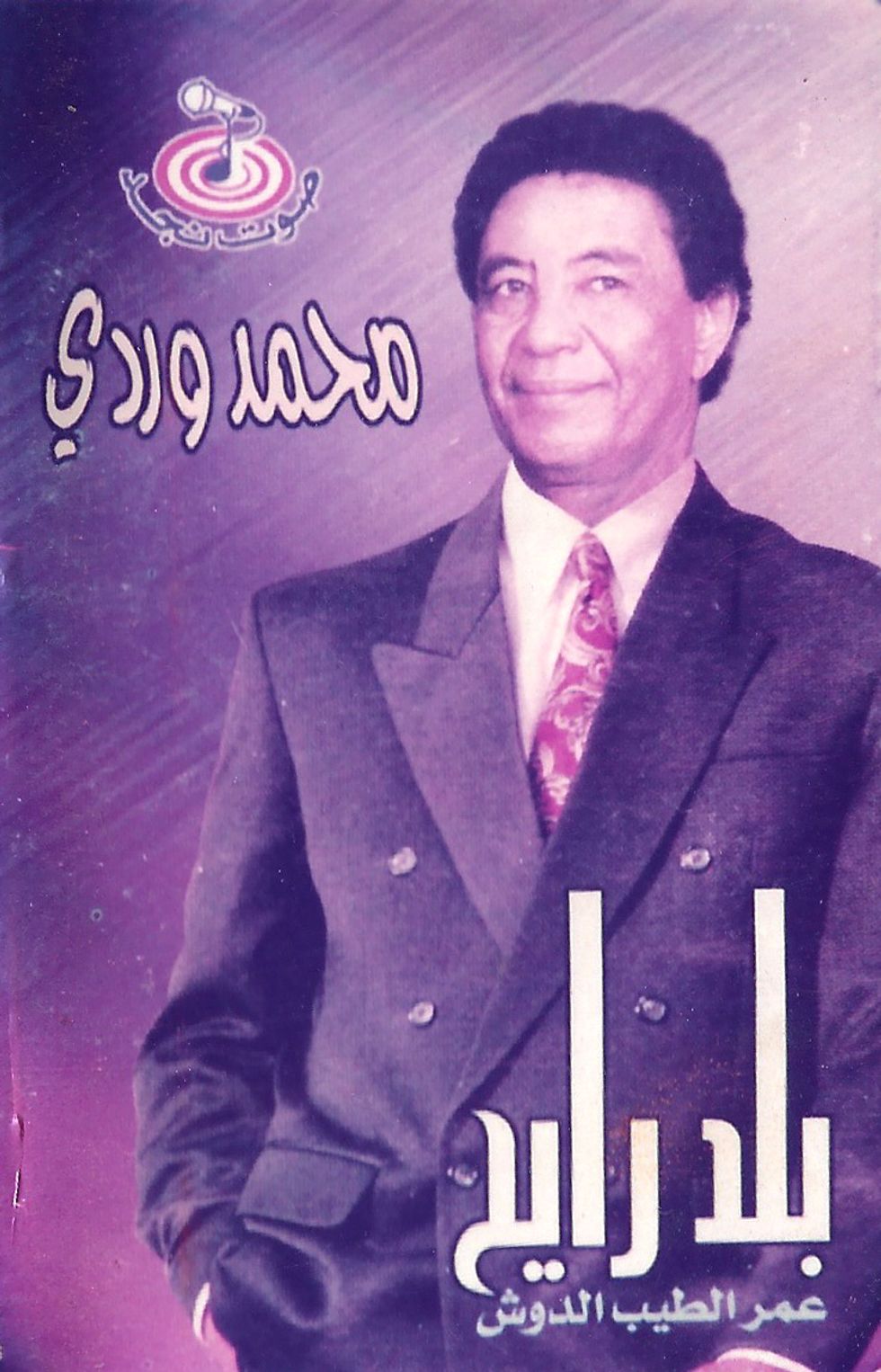

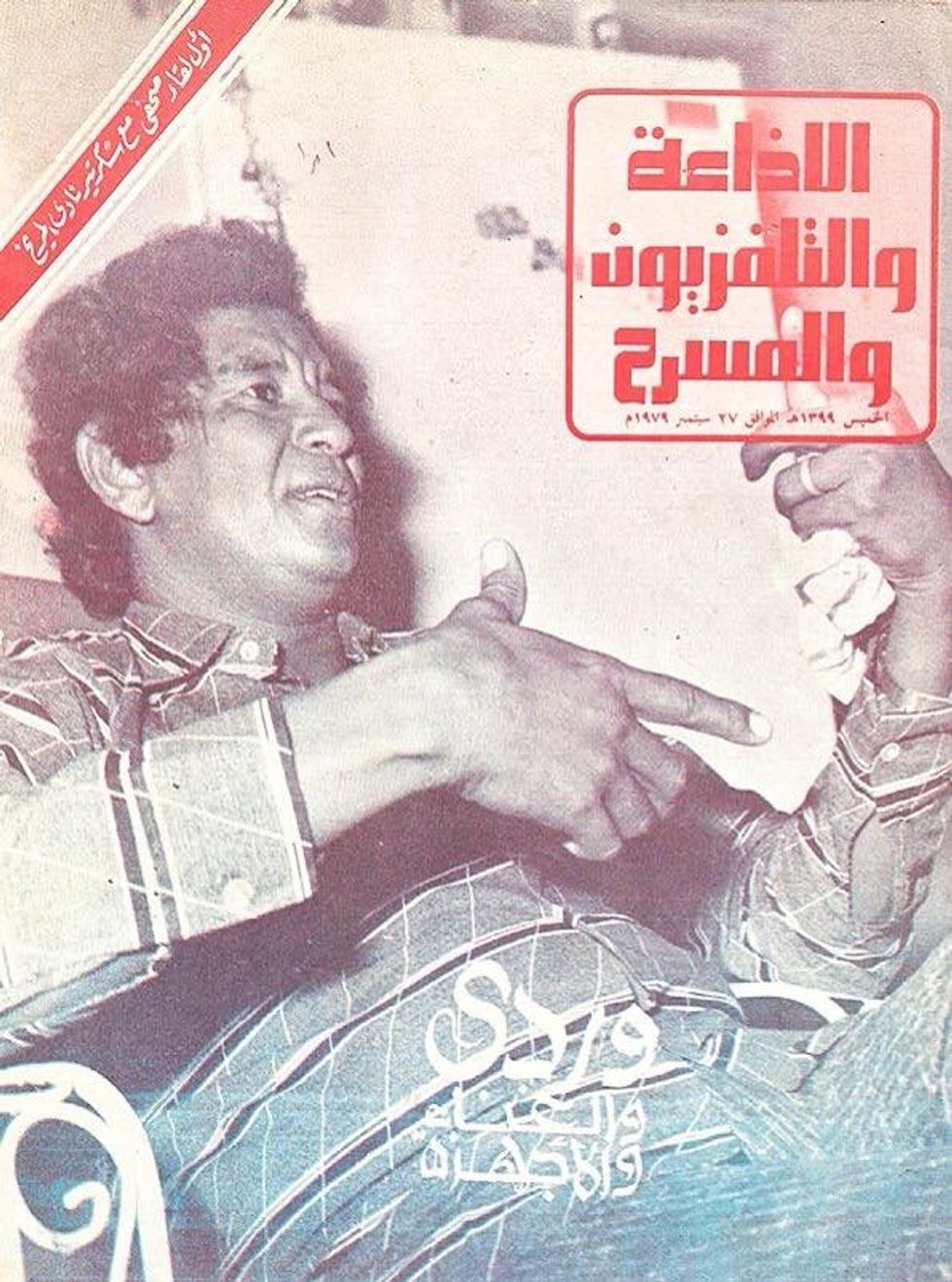

The Story of Mohammed Wardi, 'The Last King of Nubia'

The legendary Sudanese singer's son, Abdulwahab, speaks in-depth about the life and times of his father, detailing his artistic and political impact on so many across the continent.

It's often confounding how someone of Mohammed Wardi's stature is not remembered in the same vein or celebrated worldwide as Fela Kuti. Wardi was a legendary Sudanese singer and activist akin to Fela in stature and impact in his music and politics. In fact, Wardi was, in many ways, the single most adored singer across Africa. The Wire magazine in the UK calls him a "cross between Fela Kuti and Lebanon's Feiruz."

Mohammed Wardi once performed at a sold-out 60,000 stadium in Yaoundé, Cameroon to a largely Francophone crowd who did not understand his Arabic lyrics but remained infatuated. A man from Mali once walked on foot for three months to Sudan to meet Wardi because the father of the woman he wanted to marry would only allow it if he got an autographed cassette and photo from Wardi himself.

In 1994, Wardi won a prize that anointed him the best singer in Africa. Politically, he fought for the ideas of his day: social justice, decolonization, redistribution of wealth, pan-Africanism. His relentless activism resulted in detention and eventually exile. His passing in 2012 was mourned from Mauritania to Djibouti.

His son, Abdulwahab, spoke to us in depth about the life and times of his father, detailing his artistic and political impact on the lives of so many across the continent.

This is Mohammed Wardi's story, as told by Abdulwahab.

(Interview has been condensed and edited for clarity)

Mohammed Wardi was a fighter. I call him the "Last King of Nubia." He is as ancient as civilization, the pharaohs, and the palm trees. The Nubian region is very rich with its beautiful scenery and views. It's a very old civilization with a very strong culture. It's the gate that leads from the north of Sudan to Egypt.

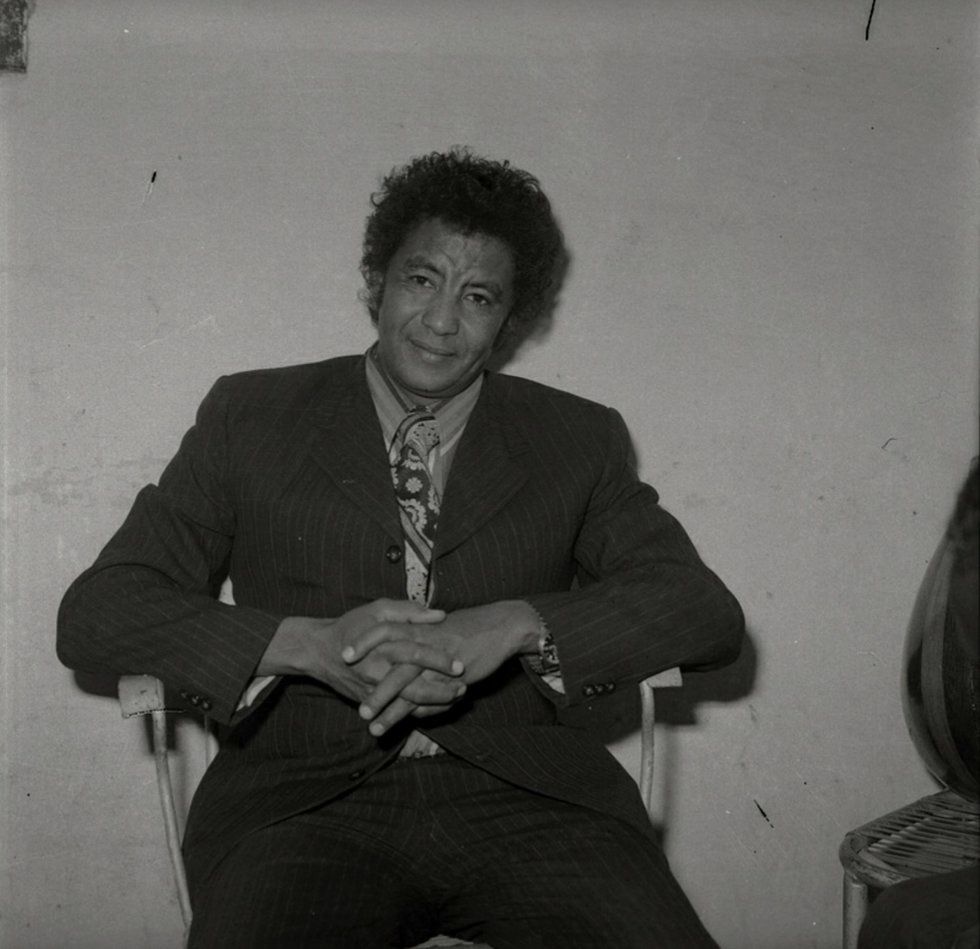

My father was born in the northern Nubian area on July 19, 1932. July 19 is a very particular day in his life because it comes back and back as we go. The first time he recorded a song on the radio was July 19, 1957. When the military coup of July 19, 1971, occurred, he spent his longest time in detention. So it's always [the number] 19 for him.

[My father] has a massive legacy with all the meaning of a legendary character. Sometimes I feel like he's a character straight out of a novel by Marquis.

When he sang to Ibrahim Abboud, a former president of Sudan, it was during a military coup. He thought the military loved their country because they didn't have political parties, they didn't just talk a lot and not do much. They were military—they had order, they had discipline. So he sang for these people, but the first political clash that came with them was when they drowned Halfa—when Sudan let Egypt build the dam that drowned the city we come from.

After that, [my father] became more conscious, and more aligned with the political left. To be more specific, he was in the Sudanese Communist Party (the largest in Africa during the Cold War). That was in the '60s, he was part of the opposition to remove colonization. They were very close to the youth and their voice was the loudest.

There were religious parties, but he was a singer, an artist, and rebellious. You know how politics can get you into some slippery areas... but no matter what, he got into politics as an artist. There's no party in the world that could tell him what to do or what to sing. They used to say that if you wanted the Communist Party to win the student vote, you just had to bring Mohammed Wardi to sing at the University of Khartoum, and that's it, everyone was going to vote for the left because he was the singer of the people.

When the May coup [which brought Gaafar Nimeiry to power] in 1969 happened, everybody supported it. Wardi came and sang because he agreed with them. It was a leftist coup that came with the same slogans that we agree with. Everybody was in the streets.

During the coup of 1971 on July 19—again we come back to July 19—he was about to be executed, but he was detained. When he was released, he didn't change his opinions and remained the same person.

In 1983 came the September Laws of Islamic Sharia. It was a very difficult year for him. The personal freedoms, being valued as people, were gone. It was an oppressive regime. He left and he sent songs for the revolution from the outside. When the intifada of 1985 came, two years after his exile, he was the singer for that revolution—because he was the singer of the people. He had zero tolerance for oppression and victimization. He fought authority, he fought the president, he fought the oppressive regime.

He left for a long time. When he was outside, in 1994, he got a prize for being the best singer in Africa. He went to America, then to Egypt, and stayed out of the country until 2001.

When he returned to Sudan, the way that people welcomed him at the airport was fabulous. It was unbelievable and unusual. He came as an artist, he came as a celebrity, he came to see his audience.

When he died, I called him the Nile. Because as long as the Nile is running, the singing of Wardi exists. Nobody can take the Nile away from the Sudanese people. It's for every Sudanese person. The other Nile is Mohammed Wardi. He will continue to be there as long as life continues to be there. Because he sings very deep songs to his people, and this is a gift from God.

Mohammed Wardi was a representative of the people. He was their voice; their civilization. He summarizes the spirit of the Sudanese people when he sings.

In West Africa, he sang in the stadium of Yaoundé to 60,000 people. They only spoke French, they didn't even speak Arabic, [so] they didn't even know what was he singing. They came to his concert because they loved Wardi. It's like when I hear Shammi Kapoor, the Indian singer, I don't know what he's singing, but I just love the songs and love the singer.

One time a guy from Mali came to me on foot because he didn't have enough money. He told me that he wanted to see Mohammed Wardi. I said, "Ok, Mohammed Wardi is not here, he's in Egypt, why do you want to meet him?"

He said, "I want to take a picture with him, and I want him to give me a cassette because I want to marry a girl, and the girl's father didn't want me, and he gave me very, very hard conditions: that if I go and meet Mohammed Wardi and bring his signature and his voice and a picture, then I will give you my daughter."

I gave him my father's number in Cairo. He took the train 'til Halfa, then the boat 'til Egypt and he found my father and took a picture with him. My father then gave him a plane ticket, and he went back home and got married. This is a person who doesn't even know Arabic. He came from Mali, traveling for three months on foot. [It shows how] my father was loved in West Africa, East Africa, and the middle of Africa.

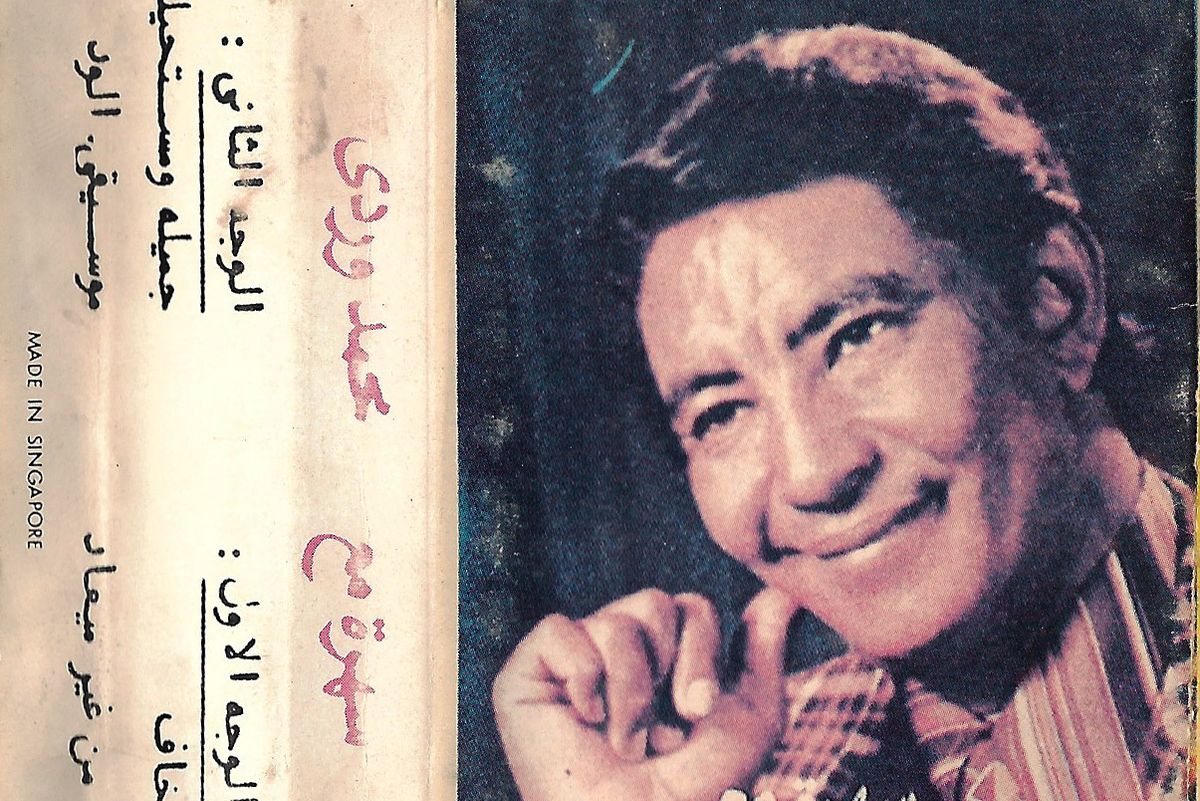

In 1997, in exile, Wardi released a cassette called Al Mursal (The Messenger). It was a song that he sang first in 1974. Sudan went crazy. This was the highest selling Sudanese album ever, until now, because he was the singer of the Sudanese people—the left and the right, the educated and the illiterate, the laborer, the farmer, everybody [loved it].

There are two personalities, two characters, two people: one in Lebanon, one in Sudan. In Lebanon, during the civil war, when the two parties were fighting, they listened to Feiruz and didn't talk. They listened.

Mohammed Wardi was my friend. If you ask me what I miss the most, since his songs are for everybody, [I would say] I miss having a conversation with him. He was the kindest, most interesting person. He knew how to chat. I had this craving to listen to him. He could tell me stories in Nubian, in Arabic. Everywhere he sat and started talking, people listened to him.

He died the 18th of February, 2012 from kidney failure. Death is difficult. I just thank God that he did not suffer a lot.

He didn't like to give advice. The only [advice that he gave] was a verse from a poem: "the sticks that stay together are hard to break." He wanted us to be one. He did not want to die outside. He wanted to die among us.

He was very calm when facing death. He waved with a smile and said goodbye. After that, the reaction was big, it was huge. To tell you the truth, I used to avoid remembering that. I could not even handle listening to his voice all this time. Just few months ago, I started to normalize that, but I was forced to stand up in front of people and to listen to his music, and to lead the orchestra, and to smile. This little courage that I have, I got it from him. God bless his soul.

Mohammed Wardi is featured in Ostinato Records' new release Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan.