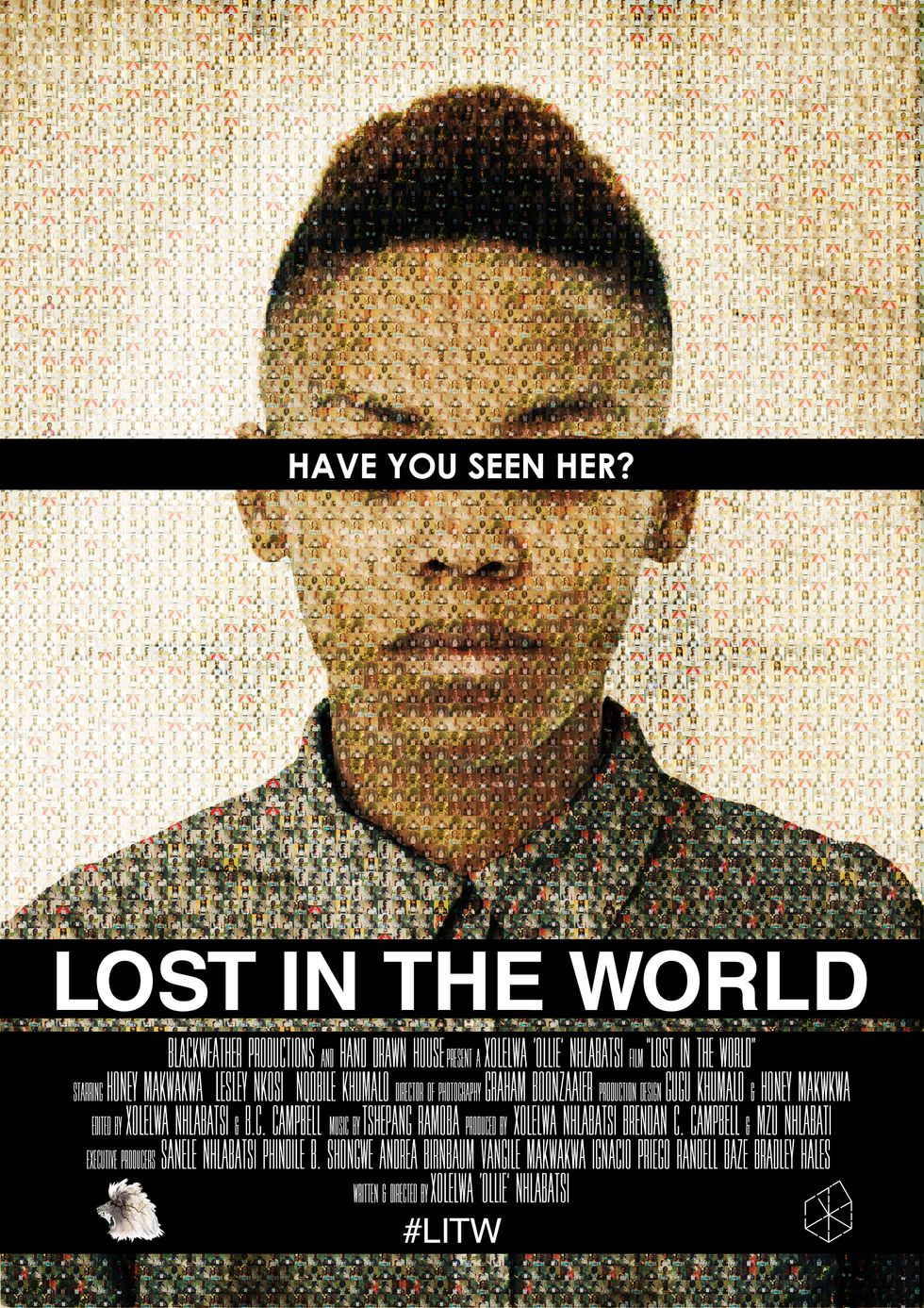

'Lost in the World' Johannesburg Premiere Q&A [Transcript]

Xolelwa ‘Ollie’ Nhlabatsi's Lost in the World tells the story of a South African police officer seeking vengeance after her girlfriend's rape and murder.

!['Lost in the World' Johannesburg Premiere Q&A [Transcript]](https://www.okayafrica.com/media-library/image.jpg?id=10997443&width=980&quality=85)

Johannesburg-based filmmaker Xolelwa 'Ollie' Nhlabatsi's Lost in the World tells the story of a South African police officer seeking vengeance following the violent rape and murder of her longtime girlfriend. The cop, played by Honey Makwakwa, loses her mind and soul in the process.

The film, a Blackweather and Hand Drawn House production, had its Johannesburg premiere last Thursday at the National Film & Video Foundation. Okayafrica's South Africa Editor, Alyssa Klein, moderated a Q&A with Lost in the World's writer/director/producer Xolelwa 'Ollie' Nhlabatsi, star Honey Makwakwa and producer Brendan C. Campbell after the screening.

What follows is the full conversation.

Alyssa Klein: My first question is for Ollie. What do you hope everyone here will take away after seeing your film?

Xolelwa 'Ollie' Nhlabatsi: I hope you guys are stewing. The initial idea was that we wanted to shed light on corrective rape. We wanted this film to be a weapon of our choosing to gather more attention around corrective rape. The problem we have in South Africa is we have a lot of victim blaming and we don’t want to talk about rape culture. I wanted to force people to watch and think upon why do we do this?

Klein: What does the film mean to each of you?

Brendan C. Campbell: The movie means a lot in the sense that it’s the first sort of big step into filmmaking for the team. That’s the biggest thing for me, on a personal level, is the fact that I can take something away from that myself at the end of the day and sort of go, “Okay cool, we’ve got our own sort of mini family set up now, and we’ll be going on all these different little adventures together.” Especially for anybody that’s seen the slate and knows what’s coming in the next four years. That’s what this film embodies for me, is looking ahead.

Honey Makwakwa: I believe that a lot of great things come from collaboration, and this was largely a collaboration. We were all at some stage in each other’s boots in terms of roles within the film. And just knowing that with the very little time and resources that we had we were able to make something that, you know, I’m absolutely not embarrassed of in the least. We’re actually capable of doing cool things, and maybe if someone threw a little money at us, we could do cooler things.

And also just to have made something that felt really really personal. I think any South African woman can attest to rape being incredibly personal to them––I’m no different in that sense. To have made something that I care so much about. I mean I made a PSA before for rape crisis, but it’s not the same. It didn’t bring things to life as much as this did. I hope that it means something in the world.

Klein: Honey, tell us about your character...

Makwakwa: Whitney is a police officer, and she’s doing well. She’s doing great, solving cases, being a hero. She’s got a girlfriend. And next thing, everything she knows is gone. Her girlfriend is raped and murdered, and the police force that she works within and that she loves shows no support. All of that turns her into someone I don’t think she knows. This is where the drugs come in, because we all have different coping mechanisms, and I think she just needs a way to kind of get through things. And eventually the police force drop the case. They’re not really interested. Just as is the case with 99 percent of reported rape crimes in our country. She’s not okay with that, and she’s pretty much destroyed by that. And her vengeance, finding out who was actually there, what was premeditated, what wasn’t premeditated. She doesn’t really care, just anyone who was involved, anyone who had a hand in it, deserves to die.

Klein: Can you speak a bit more on how the film draws from real-life experiences?

Nhlabatsi: Initially I wrote the script four years ago, but they were a heterosexual couple. And I left the film sitting there. It didn’t mean anything, it didn’t have much meaning to me as it was. And then there was a German newspaper who came down here to look at the all-lesbian football team in Katlehong. They went to look at corrective rape in the townships and see what is actually happening, because I suppose they didn’t really know what corrective rape was. And then I was assisting them, I was basically their fixer so I was their babysitter for the duration of that time, and in that time we went to a lot of interviews with ladies who are rape victims, who are friends of rape victims. And they were telling us all the same stories. The main inspiration for why Lost in the World is the way it is is because they showed us a place in Katlehong where there’s no roofing, there’s a bunch of trash in the place. There were kids playing and what not, and the kids actually found one of their friends dead, raped and murdered there. And then I think a week later the police put like one strap up, but you could easily walk in if you wanted. And still today that case hasn’t been solved. I found out that a lot of these cases weren’t solved. I knew about corrective rape, but I didn’t know the extent of how the victims are treated through our justice system. I wanted to hopefully give some sort of sympathy or some sort of understanding that even though you didn’t get justice, you’re not alone. I wanted this film to embody that “fuck them, kill them all, whatever you need to do to survive.” That was the inspiration for the film.

Klein: What has the response been outside of South Africa?

Nhlabatsi: Pretty good. When we showed it in London for the Film Africa festival, one lady asked “What is corrective rape?” And I was like, “Okay cool, great. Now we’re having a debate where I can describe and tell you what the fuck is going on back home with our very unique situation.

I thought that the local market would be more receptive of it, but it seems like the international people are more receiving. I think because they can see it as more of an art form, and maybe South Africans see it as shaming themselves, or guilt tripping themselves, which it is. If you feel guilty, you need to fix that, you need to work on that. So these situations aren’t allowed to happen. If there were more people around these ladies, and more people in power supporting them and against women abuse, then we would have maybe more money to find justice or just to give it more of a spotlight.

Klein: What are your plans for the film in the future?

Nhlabatsi: It’s currently online. You can get it on Lust in Translation as a part of the New Queer Visions Film Festival strand. It’s part of a grouping of other short films that talk about LGBT issues. But eventually, we’re going to put it on YouTube. I’d like it to go to schools. I’d like it to be used as an educational tool. I think it could shed light or give people a different perspective if they didn’t understand. I just want people talking. That’s the point.

Audience member: Because I’m not in the film world, it was very difficult for me to understand going from one scene to another. My typical movie, the scenes usually follow a certain sequence. Can you unpack the thinking behind that?

Nhlabatsi: The reason for why it was nonlinear, I didn’t want people to be comfortable watching this movie. I want you to feel Whitney’s character. I want you to feel this loss and this “what the fuck is going on?” thing all the time. It’s a tool that we use to help you guys, I suppose you see it as not very a helpful tool, but I think that your description of it is the point because you’re also kind of confused and kind of lost with it. It forces you to pay more attention to the film, and then kind of figure it out yourself. But I suppose the victims of it don’t have that. All they have is this feeling of confusion and lost. I wanted to translate that to the audience. I didn’t want it to be easy for you guys to watch. I wanted you to go home and stew.

Audience member: You spoke a bit about a journey you’re going to be taking on a slate. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

Campbell: The next step after this is another short film called Into Infinity, that’s a little bit more broader spectrum, a little bit more mass appeal sort of flavour... After that is a feature film called Nefarious Creatures which is a film about the seedy underworld of Johannesburg. After this is another feature called Roach. It’s a bit of a creature feature, it’s a bit of a comedy, it’s a bit of a horror… And then last, but definitely not least, this is sort of the culmination of everything we’ve done up until this point, will be an action-buddy-comedy called Bank School, which will be our first summer blockbuster type of film.

Audience member: What inspires each one of you in this industry? And then secondly, when you think about five years from now, what is the key message that you’d like the audience to take out of your films?

Nhlabatsi: I think, because of my unique history and background, I see a lot of discrepancies with different things that you usually don’t see in a lot of mainstream films… The thing that we see a lot is that we take a European or an American film and we kind of just translate it here, but we don’t make it for us here. We didn’t create it. It’s not a genre that we have made up, it’s just something that we’re taking and translating for ourselves. But what I want to do, and what we’re striving to do, is make unique South African things, where it can’t be anywhere else in the world. It literally cannot be. And that’s what inspires, to make those kinds of films. I want the South African youth, and of course people to a larger extent, to feel patriotic when they see the slate... Like that American pride, when Americans watch Captain America they see themselves and they can be like “Yay, look at us. We’re so fucking great.” But we don’t have [that]. We want to make films that are like that on a Blockbuster scale.

Makwakwa: The inspiration is storytelling. I think all our stories are important. If you grew up sitting and listening to [grandmothers or your aunts] telling you stories, there’s nothing more magical than that. And I think each and every one of us has a story. And I think it’s just like oh god, if I get a chance to be part of the interpretation of that story, for me that’s just so sacred and incredible and worthwhile. So that’s the inspiration.

And in terms of what I’d want someone to walk away feeling, in terms of films I’d like to see us creating, I do think that it’s important that we start to do a little brand South Africa in our work. Something that isn’t hijacking would be great.

But also just, I would really love to tell simple stories, do you know? I’m at the point where as a black female actress I really hope to one day play a role where my character’s complexities are just that. And not speaking for my entire race and gender. So that other black girls who maybe see that representation, wherever that thing might finally show, actually feel like their experience matters. The black experience on celluloid is so one-dimensional. And like, the black experience it just doesn’t matter. Why can’t we just have 56 minutes of hair? Black hair talk, that isn’t preaching. Why can’t we have a film about that? There’s so much of our identity in it. And I know a bunch of women who could do more than 56 minutes of talking about that. I’m sure we could write a story around that. I’d like to get to that level of privilege within this industry one day.

Campbell: I feel like I’ve been sort of granted the opportunity to tell stories, and that for me is sort of like the greatest job, and the greatest responsibility in the world. It’s the oldest form of empowerment, it’s the oldest form of just making people feel good about themselves… If you’ve got that ability, and you can do it, you’ve got a social responsibility to really just save people from all the hate and darkness and fear and bigotry that we live with on a daily basis.

Audience member: What would be your key learnings from making this film?

Nhlabatsi: That we can make it. That we don’t have to ask people for permission. We don’t have to wait for permission. We don’t have to wait for acknowledgement. We can just go ahead and do it for ourselves.

Audience member: What was the choice behind not showing the rape? You showed drugs, violence, why not the crux of the story?

Nhlabatsi: My first audience was for rape victims, so I didn’t want to rehash it. They live that all the time. It was less about the glorifying blood and stuff. That wasn’t the point. The point was for audience members to take away whatever they feel, or however they relate to it. And putting the rape in it, it’s kind of like a translation of that hidden guilt, that you’re like “what is this thing?” It’s all about rape but you don’t see rape.

It wasn’t that kind of film. I think people might come into it expecting rape and they don’t find it. But then, I hope that what they do get out of it is our message.

Audience member: I was just really interested in the choice not to show it. And also just the fact that you wrote it. As women we always feel like rape is our problem. And actually it’s not, it’s a male issue. So kudos to you for writing from a male perspective something that affects us every day.

Nhlabatsi: Women are my family. There’s not many of us [guys] left. The films I like are usually female-led films, because they show a different perspective. The male gaze and the male privilege is so boring, and you’ve seen it again and again. Women have a better perspective and more understanding than men. Men are kind of, unfortunately, dick-driven.

Audience member: You spoke earlier about how your initial audience was the rape survivors. When you were creating this, who were you making it for?

Nhlabatsi: It was victims of rape initially. At the time, and I still think now, there’s not really a film from the rape victim’s perspective. So the police might be more important in the film. I wanted it to be a film where Whitney’s character embodies this wraith, if you would like, that is uncompromising. She will not stop until she gets what she wants. If a victim of rape can see that this woman has this drive to do whatever she wants, to stop whatever she wants, then you can also, in whatever capacity you have, and whatever you need to do, you can also do it. There will never be justice, and you will never have that comfort, but as long as you know that you yourself had the agency, and you didn’t let other people take it away from you, and wait for people to give you justice, like you take it yourself, in whatever capacity… The point is to say “Yes, you are a victim. But you mustn’t take that connotation of victim and shaming.”

Makwakwa: Don’t internalise the shame, the external shame

Nhlabatsi: It’s not yours to hold.

The Lost in the World team would like to thank The NFVF for hosting the Johannesburg premiere of Lost in the World.