Meet the AKO Caine Prize Shortlist

We spoke to the writers who've been shortlisted for this year's prestigious AKO Caine Prize for African Writing.

The Prestigious AKO Caine Prize Announces 2020 Shortlist of African Writers.

The AKO Caine Prize for African Writing announced its shortlist for this year's award earlier today. Perhaps one of the most highly-anticipated literary prizes on the continent, the AKO Caine Prize celebrates 20 years of honouring diverse and high-calibre African writers including the likes of the lateBinyavanga Wainaina, Tope Folarin, No Violet Bulawayo and Namwali Serpell.

This year's shortlist features writers who hail from Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Namibia. Erica Sugo Anyadike, Rémy Ngamije, Chikodili Emelumadu, Irenosen Okojie and Jowhor Ile were all selected virtually by a panel of judges due to the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak.

Describing this year's shortlist, chairperson of the judging panel and Director of The Africa Centre, Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp CBE says, "We were energised by the enormous breadth and diversity of the stories we were presented with––all of which collectively did much to challenge the notion of the African and diaspora experience, and its portrayal in fiction, as being one homogeneous whole." Tharp adds that, "These brilliant and surprising stories are beautifully crafted, yet they are all completely different from one another. From satire and biting humour, to fiction based on non-fiction, with themes spanning political shenanigans, outcast communities, superstition and social status, loss, and enduring love. Each of these shortlisted stories speak eloquently to the human condition, and to what it is to be an African, or person of African descent, at the start of the second decade of the 21st century."

The winner is set to be announced later this year.

In the meanwhile, get to know the writers who've been shortlisted for this year's prestigious AKO Caine Prize for African Writing in the interviews below.

Read our interview with Erica Sugo Anyadike.

Read our interview with Rémy Ngamije.

Read our interview with Irenosen Okojie.

Read our interview with Chikodili Emelumadu.

Erica Sugo Anyadike

Erica Sugo Anyadike is a Tanzanian writer who works in the film and television industry.

Photo courtesy of Erica Sugo Anyadike.

Erica Sugo Anyadike is a Tanzanian writer who works in the film and television industry. Her work has been featured in publications such as Kwani, Writivism, Femrite and Karavan. Anyadike has previously been shortlisted for both the Commonwealth Short Story Prize and the Queen Mary Wasafiri New Writing Prize. Her short story How to Marry an African President, which was published in Commonwealth Stories, has been shortlisted for this year's AKO Caine Prize.

We caught up with her to talk about being shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize this year and what that means to her as a writer.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little about when the writing journey started for you.

I actually come from a television background, so I've always been a writer. I think I've written for television more than anything else and I've always loved writing. I was a complete nerd at school. I've always been writing and winning various essay prizes but I ended up veering into film and television and working as a podcaster. The two disciplines aren't completely separate from each other and in fact, complement each other. While writing a novel or a short story is very different from writing a film, there are similarities too. But in short, I've always written.

What possibilities would you say you discover when writing fiction?

I think for me, I find certain things completely fantastical and cliché. I think when you write for a living, you approach writing as a discipline––you're not waiting for a muse or for lightning to strike. But I have found that when there are times when a story will kind of grip you around the throat and just refuse to let you go. It says 'I want you to write me out.' I think the aspect of discipline and learning the craft is valid, but there is a little bit of the magical to it as well. There is also a mystical process when something just demands to be written. So it could be a character, it could be an image or an issue. This story was one of those where it just kind of knocked about in my mind and then I sat down trying to find the point of view. Then finally, when I said, 'This is how I want to approach the story', it literally wrote itself in a day. That was it.

What inspired your now shortlisted story How to Marry an African President?

I am really not interested in 2D representations of women in the media. I know people think [the story] is about Grace Mugabe, and it sort of is. But it's also not about her if you know what I mean? It could be a story about Imelda Marcos, for example. Basically, it's a story about ambition. Reading these 2D representations of Grace, I started thinking, 'There's got to be more to a character like this.' Obviously I don't pretend to know her. I have no idea what she's really like and I've never met her in my life. I was much more interested in why this woman became this iconic representation of excess and greed. I thought, 'What is it like for a woman who was just a secretary to get married to a president? How did her life change?'

I wasn't interested in vilifying Grace for Mugabe's downfall. I think at one point people were like, 'Well, he really went off the rails when he met her and he used to do this and he used to do that.' I wanted to know why they were infantilising him like he didn't have a choice. I wanted to know why they were reducing her. She is a 3D human being and somebody who has agency. And so I wanted to write a story about a character who has wants and needs and who feels, and is not just one dimensional.

Who would you say are some of the writers, African or otherwise, that have inspired you in terms of your own career as a writer?

I think I read widely and I've been inspired by so many different people. Some of them are even my contemporaries. I mean, there are times when I look at somebody like Lesley Nneka Arimah and I'm just in awe of what she does and how she uses language. It's incredible.

I liked Tope Folarin's story for Caine. I enjoy Lorrie Moore and how she used the second person in an anthology of stories called Self-Help. I also really like the writer called Celeste Ng. There's a young Zambian woman named Efemia Chela. You know when you read something and you're just so ecstatic? She wrote a story that way about a chicken.

But if I had to pick one, I would probably say it's Arimah. Arimah's probably been my favorite. There's a story she wrote about a girl's relationship with her mother and her father that actually won the Commonwealth Prize. That was, for me, a triumph of writing.

What aspect of the short story format do you find most challenging?

When I think about what I found the most challenging, I think of how you are supposed to evoke one thing in a short story. You can't do everything in a short story. I think you have to really drill down and distill the essence of what the story is about. Sometimes it can be something as clinical as knowing exactly what you want to say or knowing where a character is taking you and the direction in which the story is heading. You don't have as much room to sort of meander and explore and so you have to be quite clear about what it is you're trying to do and the message that you're trying to get across.

What does it mean to you to be shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize this year?

When I lived in South Africa, I would wait for this Caine Prize shortlist to come out. I would read all the prizes that were there. For me, writing has been a growth process. I am one of those people that is interested in craft. I have never been satisfied with just doing something. I've always wanted to figure out how I can do it better. Writing is a tool which I think you constantly have to develop.

Reading those initial Caine Prize writers, I remember being in awe of what they were doing.

"When you're writing, it's a solitary process."

When you put a story out into the world, and I'm not going to lie to you, I think validation from other people is important. When other people reiterate that the story means something to them or that the story moves them, it's just a great feeling. It is the biggest prize on the continent. I feel amazing.

What would it mean for you to win the AKO Caine Prize this year?

I mean there's something a little bit special about this year. I shouldn't probably incriminate myself, but let's just go for it. Let's just do it. I've been watching what's happening in the world and just watching the role of women change in terms of the Me Too movements. Even just looking at what's happening with Biden and the woman who's leveling some allegations against him, and how women are standing up, refusing to be put into this kind of ghetto. We're not going to sit pretty for men's sexual pleasure. We're not going to be one or the other thing.

I think as an African woman, starting to speak to some of those issues within our own society, is really important to me. I'm not interested in portraying women as solely good or even solely bad. I'm much more interested in the global conversation around the complexity of women and sometimes even the complexity of the choices they make.

If I managed to convey that complexity and the story won, if people actually responded to what I was trying to do, then I think that it would be a victory for more than just me.

Read Erica Sugo Anyadike's How to Marry an African President here.

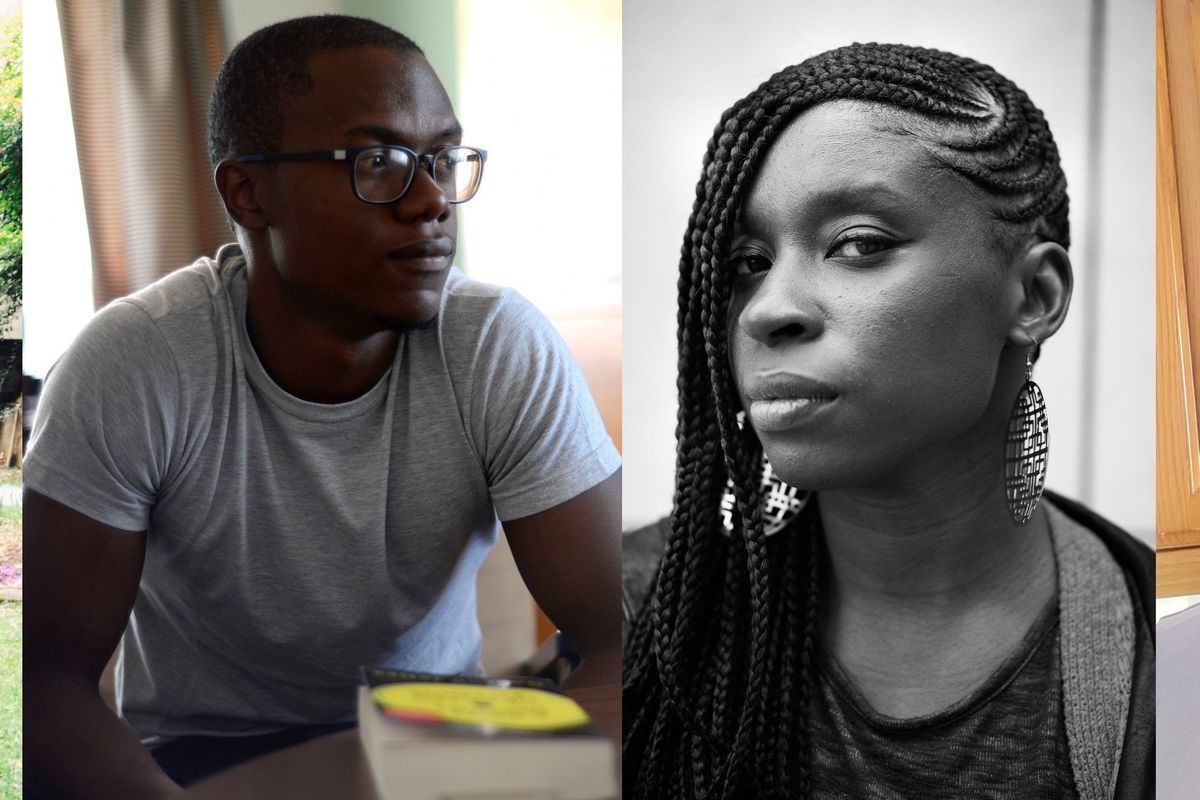

Rémy Ngamije

Rémy Ngamije is a Rwandan-born Namibian storyteller.

Photo courtesy of Rémy Ngamije.

Rémy Ngamije is a Rwandan-born Namibian storyteller whose work has been featured in several publications including Litro Magazine, AFREADA, The Johannesburg Review of Books and The Kalahari Review, among several others. His debut book The Eternal Audience of One was published in 2019 by Blackbird Books. Ngamije is the editor-in-chief of Namibia's first literary magazine, Doek!. His short story titled The Neighbourhood Watch, which was published in The Johannesburg Review of Books, has been shortlisted for this year's AKO Caine Prize.

We caught up with him to talk about being shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize this year and what that means to him as a writer.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little about when the writing journey started for you.

I'll separate it into two and say that the desire to write started in primary school about the second or third grade, which is when I moved to Namibia and I was learning English. Our teacher was a very committed English teacher and so she used to read a lot of stories to us: folktales, nursery stories, those kinds of things. I think everyone in our grade wanted to write because she read to us a lot of Roald Dahl stories. That's the desire.

But the actual practice of writing would probably have started in 2008 when I was in university and I was studying English literature at the time. I was working for the UCT student newspaper. So that's where I started writing for publication. I think that independence towards writing my own stories or stories I was interested in started in university in 2008.

What possibilities would you say you discover when writing fiction?

I would say it really comes down to identity and the freedom of independence that comes with being able to create characters who are either like you or not like you. And that's really the biggest thing that I enjoy about writing and that I find fiction gives me at least. Most of my stories are set in locations that I've been or places that I've read about.

"I get to create diverse characters and personalities that are sometimes absent from my life..."

It's always an exploration of what could have been or who I could have been, but who I was not because 'Black people don't listen to pop music' and I like Taylor Swift. I'm betting fiction is always a good way to explore all of these contradictions about kids who are different from their parents. [It's about] Black people who do not follow the traditional narrative that has been forced upon them. That's what fiction offers––alternative ways of being.

Who are some writers, African or otherwise, who have inspired you?

On the African continent, we have to start with my formative years when I was learning English literature. So the very first African writer we got to read was Chinua Achebe and his Things Fall Apart. We then went on to A Man of the People and Anthills of the Savannah. So that's really the first African author that I got to encounter although that was in an academic setting. When I discovered independence and started nurturing my own interests, I started discovering writers such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o from Kenya, Ama Ata Aidoo from Ghana, Buchi Emecheta from Nigeria.

I've also always enjoyed writing from Latin America and the Caribbean because of the diaspora over there. My favorite writers are Jamaican writer Marlon James. I also enjoy Zaidi Smith who's half-Jamaican and Arundhati Roy, an Indian writer who wrote The God of Small Things, which is a book that I just absolutely enjoy. I am also a big William Shakespeare fan. As old-school as that sounds, I really do love his work. More recently, South African writer Zukiswa Wanner, Maaza Mengiste, Leye Adenle, Mohale Mashigo, Nozizwe Cynthia Jele, Sarah Ladipo Manyika as well as Masande Ntshanga from South Africa.

I've always enjoyed reading the work of those writers. It's just so sharp and clear.

What would you say is the most challenging aspect of the short story format?

I guess it's creating all of that drama and tension in a short space of time. In a novel, you're allowed to slow down and speed up. Whereas in a short story, it's like a sprint. If you think of the hundred meter sprint, within those 10 seconds and 100 meters, there's so much drama that happens. You're trying to create all of that in a 5 000 word or 3,000 word goal––a very big challenge.

The physical act of writing a short story is hard because you literally have to sit down in one sitting and get it all out. You can edit later of course and rework it. But that first sit-down to write the whole thing is always challenging physically. With other forms, you can always stop, drive, get up, go do something else or listen to music, but I think a short story is a little more challenging in that regard.

What inspired your now shortlisted story The Neighborhood Watch?

I was living in Cape Town a couple of years ago and when I moved out of res, I started noticing that there would be people who would go around on days meant for collecting rubbish, emptying bins and whatnot. The neighborhood I lived in was predominantly white so they were very anxious about some of these characters being around. I wasn't. I knew these guys were trying to survive just like everyone else. And so it started from there because I'd see it regularly and when I moved back to Windhoek [Namibia], it became more regular. Little by little, the idea stuck with me. Then one day, I happened to bump into one of these people and they're ordinary people just like you and me: they have dreams, they have aspirations and they've got daily challenges.

And so the idea behind the story was to [shine a light] on the people who are generally invisible in Windhoek and Cape Town where I also lived. About a year-and-a-half ago, I sat down to conceptualise what these invisible people's days look like, what they do and how, what they fear––all those things.

I was really inspired by their story and I'd never seen them written about in Namibian literature. I know there's literature about them elsewhere.

What does it mean for you to be shortlisted for the Caine prize this year?

First of all, it is incomprehensible. Honestly, I do not understand what that means because I don't know the scope and the recognition is unheard of. It's never happened to me personally so I don't even have prior experience. I do know though, and I hope, it shows that there are stories in parts of the world that you might not have heard of. I hope this shows people that Namibians might not be publishing a lot, but there are people trying to broadcast. It's not like the literary scene is made up of just Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia and South Africa. There are other places on the continent.

I feel like with this shortlisting, I've already won just having managed to write and complete the story. Personally, that's a victory to finish anything. Everything else from there is just a bonus.

What would it mean for you to win?

So for me, this shortlisting is as far as my imagination has gone. It starts there. What it would mean to win is quite an intense question. I think for me, to win would be a weird validation for all those kids who think about writing from a very young age, but aren't given the time, the space or the resources to actually pursue it meaningfully. I think it will be a validation of the dream and the desire that I had when I was young because I was told from a very young age that [writing] is not what Black people do in Windhoek. We could instead become accountants, engineers and doctors. More than anything though, because I don't know what the future holds, I can tell you that it really would justify a lot of the risks and losses that I've encountered along this road.

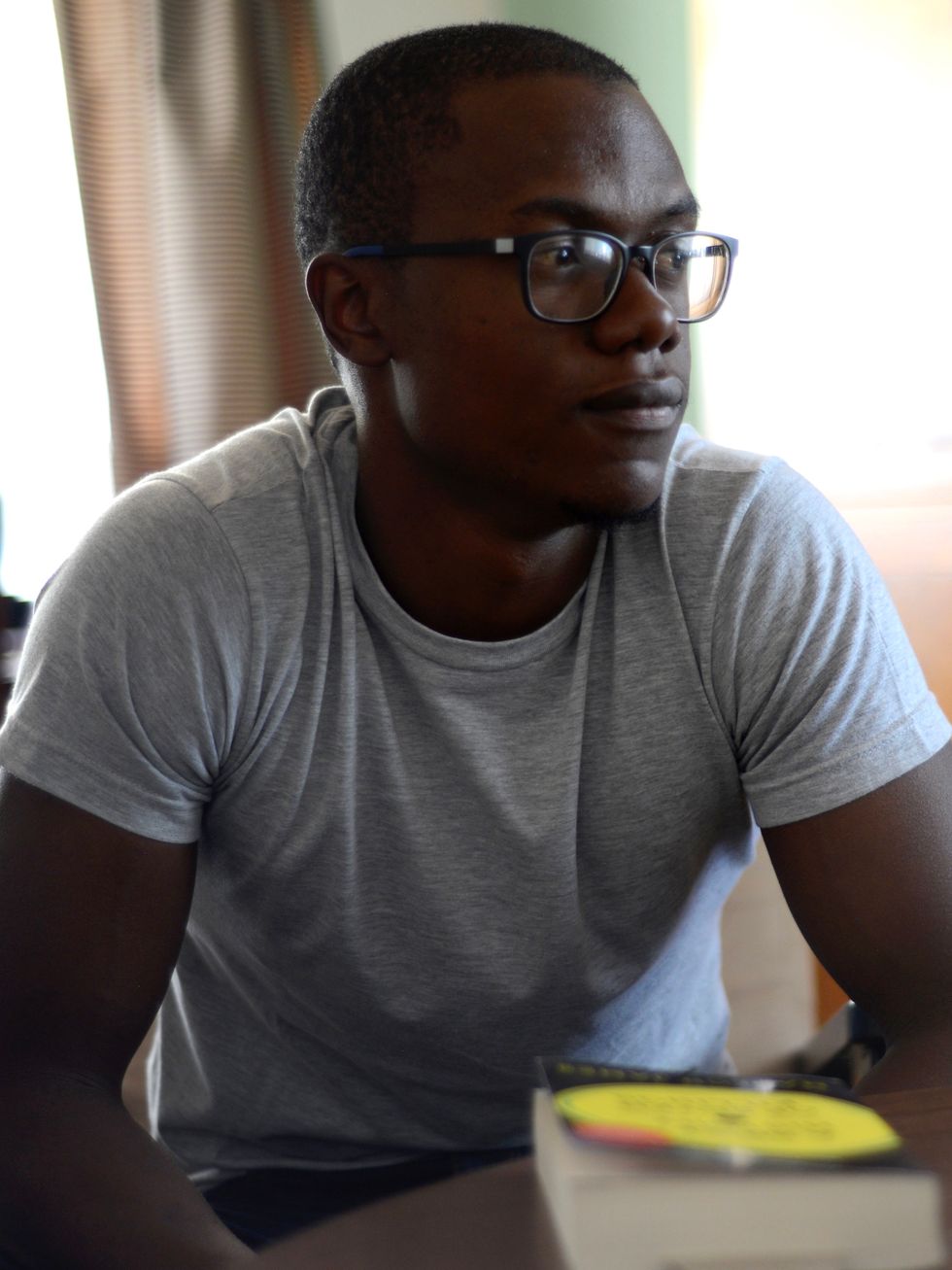

Irenosen Okojie

Irenosen Okojie is a Nigerian writer based in the UK.

Photo by David Kwaw Mensah.

Irenosen Okojie is a Nigerian writer based in the UK. Her work has been published in several publications including Huffington Post, The New York Times and The Observer, among several others. Her 2016 debut novel Butterfly Fish was awarded the Betty Trask Award. She's since published additional titles including Speak Gigantular and Nudibranch. Her short story Grace Jones, which was published bytheHachette Book Group, has been shortlisted for this year's AKO Caine Prize.

We caught up with her to talk about being shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize this year and what that means to her as a writer.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little about when the writing journey started for you.

I've been writing since I was a kid really. I was writing poems because I was a voracious reader as a child. I always had an observer's eye and would write for different magazines throughout the years as well. I wrote for a filmmaker's magazine at one point, because I love films. And then I guess about nine years ago, I started seriously thinking about the novel. I had the idea for my first novel around that time and then about three years later, I started actively writing it. I then took a break from the novel and started writing short stories.

I loved writing short stories because it showed me that I was an experimental writer who found my voice writing the short form. After I'd written that first collection [of short stories], I went back to the novel and it gave me real confidence to finish it properly. By the time my first two books came out, I'd written a novel and a collection.

What possibilities would you say you discover in writing fiction?

It's a great way of expression and interpreting the world. It's also almost another limb for me.

"I can't remember a time I didn't write and it's really opened up my world."

I consider a writing space to be a transformative space. I'm sure a lot of writers feel that way too. You can take things that maybe caused you great pain and create art from them. The process of going through that is really quite special.

You can also claim things when writing as well. With my first novel, I wrote about the Benin Kingdom. My family is from Benin in Nigeria and it has a fascinating history, rich in culture and architecture. I moved to England when I was eight-years-old and my father started telling me about Benin and the Benin Kingdom. Through my novel, Butterfly Fish, I was able to write about that cultural inheritance. And I was really proud of doing that because very often when people talk about Black history here, they talk about slavery. I knew that that's not the only history that we have.

What would you say is the most challenging aspect of the short story in particular?

I think that with short stories, you have a short space of time to really engage the reader. They have to be really quite striking because you're doing less with more. I feel that short stories are undervalued in a way, because they're really hard to get right. But what the forum does is that it allows you to do things that you perhaps wouldn't do in a novel. And I really love that aspect about it. I love writing these subversive stories. I have a really playful mind so the short form is a great space to allow me to explore different narratives whereas with the novel, you sit with the same idea for a long time and there can be the possibility that you lose momentum.

When I write short stories, I'll write one short story a month because I'm just so excited to get these ideas out there. And it's really a way of, I guess, stretching your arsenal if you're able to do both. I enjoy playing with both the novel and the short form.

What inspired your now shortlisted story Grace Jones?

I'm a huge Grace Jones fan. I've always loved her music and her aesthetic. I think she's just a really unique and standalone artist. Just looking at her visually, I think is amazing. And she has really challenged people's ideas of gender expectations before it became a thing. Grace was doing that years ago. I've always wanted to write about her. This story, Grace Jones, really was inspired by her and is an ode of sorts to her. The story follows a Grace Jones impersonator who looks like Grace and is able to get a job as an impersonator, but also has a few dark secrets of her own. Throughout the story, the reader gets to find out what those secrets are, and how they have impacted her years down the line.

Which writers, African or otherwise, would you say have been instrumental in your own work as a writer?

I really love the work of Toni Morrison. I say that in a lot of interviews, but she's really incredible. I read Jazz as a teenager and it blew my mind. What she did with that novel, to write a novel that mimics a musical genre, is pretty special. I went on to subsequently read her other books, which equally blew my mind. Beloved was absolutely devastating, and The Bluest Eye. Every single book of her body of work is astonishing and we're just so lucky to have that still.

Jamaica Kincaid is a huge influence on me. Again, she's another really unique writer. And when I was writing my stuff, one of the things I worried about was how it would be received because there aren't that many experimental Black writers around. When I read Jamaica Kincaid, she gave me permission to do that because she's absolutely phenomenal and equally experimental.

I'm equally inspired by Ntozake Shange who wrote the play For Colored Girls. It's like three forms in one book because it's a choreopoem, a play and a novel. It was just astonishing that she did that. There's Amos Tutuola, who wrote the Palm-Wine Drinkard, Margaret Atwood and June Jordan, a Black American poet that I love.

What does it mean for you to be shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize?

Well, I think it's great. It's a real honour and privilege. Some of my writing heroes have been shortlisted or have even won the Caine Prize in the past. I'm thinking of the great Binyavanga Wainaina, Chika Unigwe, who I really love, Billy Kahora too. It's a real honor, I think, to be shortlisted for this prize but I'm blown away that I was shortlisted. Like I said, my stuff is more experimental and so that means the world is opening up to this sort of writing.

What would it mean for you to actually win the AKO Caine Prize this year?

I don't want to jinx anything because I'm sure the quality of the shortlist is probably excellent, but it's a fantastic prize––very highly regarded on the literary scene. Just to be shortlisted is amazing. I'm delighted that one of my short stories was shortlisted for the Caine Prize and I wish everyone the best of luck. Obviously the quality of writing is always outstanding and so winning is very subjective. One group of judges will pick one winner on one day and on a different day, another group of judges will pick another winner. So I don't take any offense if I don't win. I just think it's a wonderful thing to have this happen because it means that hopefully my work can be introduced to an African audience as well. I'm really proud of that.

Chikodili Emelumadu

Chikodili Emelumadu is a Nigerian writer.

Photo courtesy of Chikodili Emelumadu.

Chikodili Emelumadu is a Nigerian writer whose work has appeared in One Throne, Omenana, Apex, Eclectica, Luna Station Quarterly and the interactive fiction magazine, Sub-Q. In 2014, Emelumadu was nominated for a Shirley Jackson Award. She was also shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize back in 2017 for her short story titled Bush Baby. Emelumadu has once again been shortlisted this year for her story What to Do When Your Child Brings Home a Mami Wata which was published in the second volume of The Shadow Booth.

We caught up with her to talk about being shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize this year and what that means to her as a writer.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little about when the writing journey started for you.

I always assumed everybody wrote so I can't really pinpoint a time when the writing journey started for me. My dad's a surgeon and my mom's a doctor and they had colleagues who were doctors as well as writers. They would gather most of the time to have poetry nights and things like that. I mean, my parents aren't writers, but they had a lot of friends who were. People from the university, people who were professors of English, and all that. I just always assumed that because we had their books in our house, people could either be writers or choose to be something else in addition to being a writer.

When I got older, I met people who, it wasn't just that they didn't know how to tell stories, they were not actually interested in stories. I thought it was sacrilege, blasphemy even. And so I don't think there was ever a point where I thought, "Oh, I'm just going to be a writer." I had just assumed that that was what everyone did.

What possibilities would you say you find or even create when you're writing fiction?

You write fiction to create worlds that you wish existed already. Those worlds don't always have to be conflict-free, because otherwise, there is no tension in the story.

I always tell people that I never knew that there was anything called 'feminism' because I always just assumed that everybody was a feminist anyway. Then I grew up and I realized again that some people were not only not feminist, but they weren't even interested in feminism as a movement. And so you want to create worlds that should exist. We don't have to wait 100 years for it because you can just create it now.

Which writers, African or otherwise, have inspired you and your own work?

It was more about the African environment than any specific writers. I wasn't born in Nigeria, but I grew up in Nigeria, which I think has been a blessing. I didn't realize how as Africans, we are willing and able to hold different beliefs and give them equal weight in our belief system, minds and in everything that we do.

For instance, growing up, we studied sciences and religious education. During your exam for sciences, if they asked you how the world was created, you gave them a scientific answer. And during religious education, you gave them the religious answer. Now, it was only as I grew up that I realised the huge dichotomy between creationism and the way that the world came about according to science.

And so when I first started writing, my stuff was pretty weird.They would say, "Oh, this is horror," or "This is science fiction" or "This is fantasy." And I just thought I was writing about life. I didn't realize I was writing any particular genre. I just wanted to write stuff that I found interesting and that I grew up with.

What inspired your now shortlisted story What to Do When Your Child Brings Home a Mami Wata?

I think nowadays you will find people doing things like occult studies and there are a lot of films where the weird teacher or the weird college professor who's got tenure, is the occult professor. A lot of kids will take his course because he's 'spooky' and then they'll drop it because it has no bearing in real life.

I was thinking, "What if we legitimized these things here?" Because you have a lot of universities abroad in America studying occult studies but we don't have that in African universities. There's a huge gap between the people. There's a sort of snobbery between people who are professors in universities and the so-called experts of traditional religion because the experts of traditional religion often haven't got any formal education. People tend to look down on them as well.

I just wanted to write a piece that had academic or pseudo-academic weight to it. I quoted people like Carmen McCain. I put her in as a footnote because she is a real professor. I envisioned this work as primarily an online piece that would allow anybody I cited therein to pick up the mantle and do their own paper which would be linked to my footnotes. This way we'd have interwoven cobwebs that all had to do with the supernatural.

In terms of the short story format in particular, what would you say is the most challenging aspect?

I think getting your message across in as few words as possible can be quite challenging but the other part of it is also introducing different forms that make the short story interesting. Sometimes you have to keep yourself interested in the story that you're telling and that includes being open to whatever format each story wants to take. The story will let you know what it is and also how long it is. You know when it should end. So I think that can be quite challenging when you have an image in your mind or a vision in your mind of what a story should be and the story wants to go another way. You just have to have trust that your subconscious knows what it's doing.

What does it mean for you as a writer to be shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize?

I'm glad that my stuff is making the shortlist because it's weird and bizarre. And if you talk to me on the street, I'll still be saying the same thing.

"I'm not writing for any awards."

If [the story] didn't make any awards, I would still be proud of it because it's what I believe in and it's what I want to write.

This is my second year of being shortlisted. I was shortlisted in 2017 and I wish I could say that it gets old. I wish I could say, "Yeah, yeah. It's all right," but it doesn't get old. And I'll tell you why it doesn't get old. I've been writing all my life and I started submitting in 2016 and then I was shortlisted in 2017. While I was submitting stories, my parents didn't actually care. They were saying, "When are you going back to work? We don't understand this thing you are doing. What are you doing? What's this?" As soon as I got nominated and people started calling them in Nigeria to say, "Oh my God, I saw your daughter in this newspaper," things changed. So there's a sense of validation.

What would it mean for you to actually win the AKO Caine Prize?

Can you imagine? I would change my number. I would change my email. I would block everyone. No, I'm just kidding. To be honest, this industry is hard so any kind of validation is good. Sometimes the validation comes from the story itself but having people say, "Good job" is also something. So if I won, that would be great. I'd be happy, but it wouldn't be the limit for me. There are other things I need to do and other forms I need to explore. Hopefully my book will be out next year. There's just a lot happening. So it will be a feather in my cap for sure.

Read Chikodili Emelumadu's What to Do When Your Child Brings Home a Mami Wata here.

- Nigerian Writer Lesley Nneka Arimah is the 2019 Winner of the ... ›

- The Results Are In: Makena Onjerika Wins 2018 Caine Prize ›

- Ghana's Meshack Asare Is First African Winner Of NSK Neustadt ... ›

- These 4 African Writers Are Killing It This Week In the Literary World ... ›

- Here are 5 Contemporary South African Books by Queer Writers You ... ›

- Celebrating 8 of the Most Influential Black South African Women ... ›

- Sci-Fi, Hip-Hop and Other South African Fantasies - OkayAfrica ›

- Sci-Fi, Hip-Hop and Other South African Fantasies - OkayAfrica ›

- Reading for the End of the World - OkayAfrica ›

- Reading for the End of the World - OkayAfrica ›

- Irenosen Okojie Wins This Year's Prestigious AKO Caine Prize - OkayAfrica ›

- AKO Caine Prize Announces 2021 Shortlist - OkayAfrica ›