Dear Lerato: I Will Not Be Buying Your Anti-Black Book

Luso Mnthali pens a letter to Lerato Tshabalala, author of ‘The Way I See It: The Musings of a Black Woman in the Rainbow Nation'

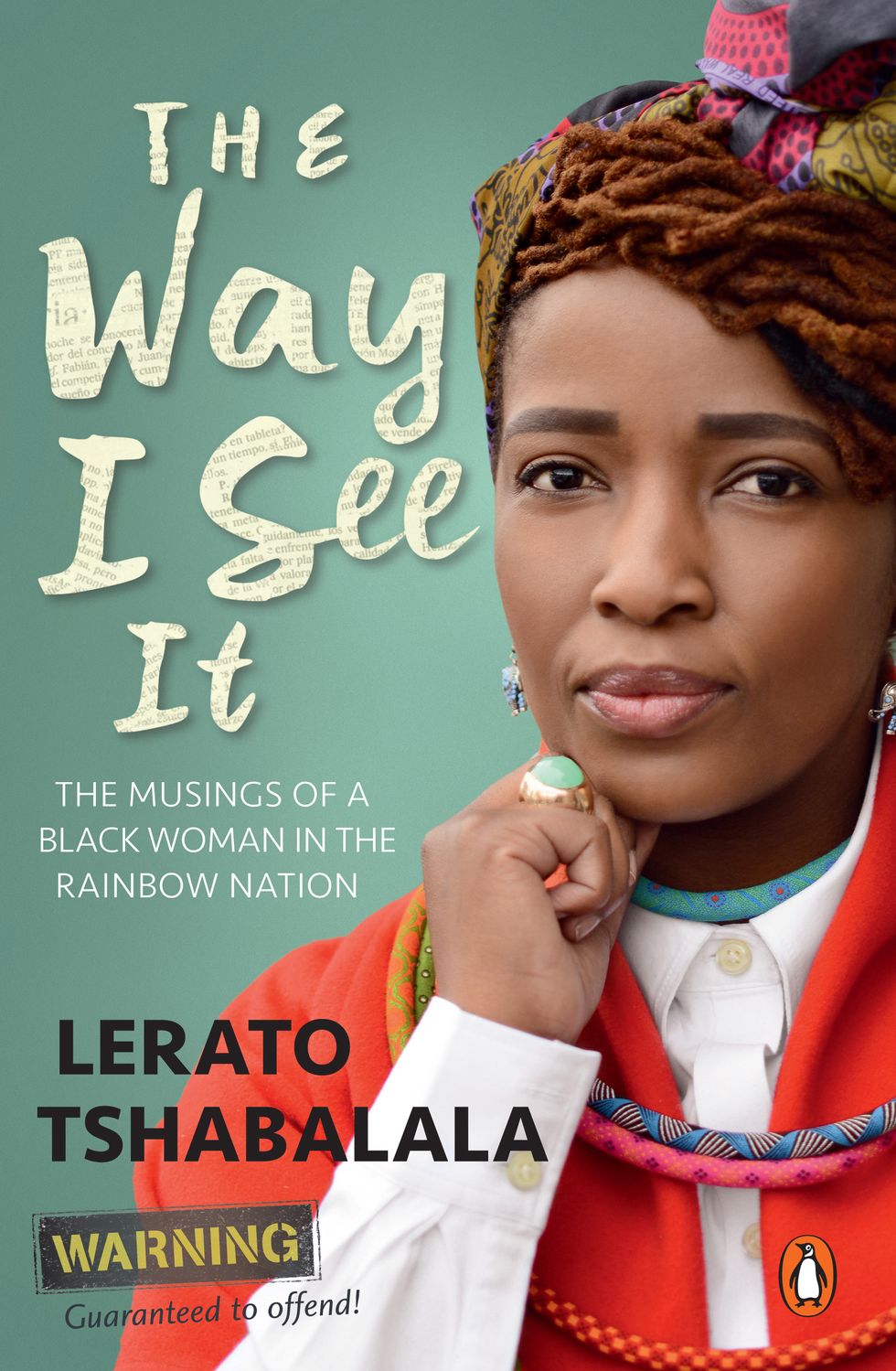

In the op-ed below, Luso Mnthali pens a letter to South African writer and editor Lerato Tshabalala, author of the forthcoming book, ‘The Way I See It: The Musings of a Black Woman in the Rainbow Nation.’ Tshabalala and her book became the source of heated debate after an edited extract, titled “Why I hire blue eyes not black guys,” was published in the Sunday Times over the weekend. In the extract, Tshabalala details why she prefers to give white people jobs over black people, writing “the majority of our people are chancers and don't give a damn about customer service.”

Reviewing a book without having read it is tricky. You can tell when someone hasn’t read something and still takes the time to talk about it. It’s an affect, a silly one at times, and a dangerous one in some other cases. In tackling a review of this book, it seemed to me to be a little bit of both. Silly because why would I attempt to do something that feels like slander in one sense, and then at once a dangerous promoting of ideas and values that are antithetical to mine? But I have to say that a discussion of Lerato Tshabalala’s book is far from mere affectation. The ideas in her book need to be challenged, whether we have read the whole thing or not. And on the strength of what I have read of it, my review will end in asking people to not bother buying it.

We’re beginning at the end, then.

Firstly, the ideas (opinions, she calls them) that have made the rounds since the publishing of Tshabalala’s Sunday Times column this weekend are shocking, to say the least. Tshabalala has written the book The Way I See It: The Musings of a Black Woman in the Rainbow Nation (Penguin, 2016) and at first she seemed excited about the controversy she knew it would cause. Now that she’s doing the radio press circuit for the book, a lot of backtracking seems to be taking place.

In an excerpt entitled ‘Why I hire blue eyes before black guys,' Tshabalala writes that black people don’t sign contracts and that they act “inappropriately.”

For many of us, it seems this has been the self-hating hatchet job of the year. Folks are wondering if she’s got Stockholm Syndrome and whether the state of cognitive dissonance she’s acting within is too thick to save her from.

“You see, white people sign contracts, give invoices and don't usually leave without finishing the job. Facts are facts. Y'all might be mad, my people, but you know I ain't lying. Now don't get me wrong, I'm not saying every black service provider is dodgy - not at all. But sadly, the majority of our people are chancers and don't give a damn about customer service”

By her own account, everyone is game for a bashing. This would be a notion that could stand the litmus test if the test hadn’t been so skewed towards bashing black people in the first place. You dip the paper in enough acid and it turns blue, but you’re not examining why the acid is there in the first place. Taken apart, Tshabalala’s notions might be welcomed by certain members of South African society. And we can’t pretend we don’t know why. A little anti-blackness on every single week this year in South Africa has gone a long way. This is this week’s story. By the end of the year we’ll have at least 52 separate incidents of anti-black bigotry and not one person in the country will be surprised by it. Our levels of shock will probably need to be thoroughly adjusted, but surprise? No. Not even when it comes from those who look like us.

The Young Turks, when taking apart Louise Linton’s ridiculous lies and nonsense of a book, noted the exact requirements for this kind of book even getting published in the first place.

When we note that these requirements are deeply settled in the South African publishing industry as it currently stands, we can’t be surprised. It was easy for this book to be accepted and published: it suits the everyday narrative that those who have antipathy towards black, brown, and queer folk––basically anyone who is different from them––will publish and also therefore have an audience, and the purchasing will and power for something of this nature.

I’m going to be honest and say I was waiting for this book. I knew it would come along one day. I wanted books on the shelf that didn’t have to have excellence, or violence, or AIDS, or politics as a criterion for non-fiction books by black authors. I wanted a black female author, especially, to write whatever the hell she wanted. In this fantasy it became a bestseller or was laughed at, talked about, lambasted, but still made her a whole pile of don’t-give-a-fuck money and that she’d be sipping kir royales, mimosas and mojitos in the Bahamas and laughing as her notifications punctuated the warm liquid air of her sparkly blue surroundings. That day has come and oh… oh. When you want to take back your wishes.

So, Lerato. I am not going to buy your book, and I recommend others do not. I’ve bought other black women’s books this year, and I’m going to buy more. I make it a point to buy not only black women’s books, but non-black people of colour as well, because - hey, I’m tired of Whiteness. Tired of supporting those who do not support us and prop up white supremacy. The prerequisite for buying a book must surely be that it will likely have something to say that I can learn from, something I have never heard or read before. I don’t believe I can learn anything from your book. I’ve heard these ugly sentiments before and they ring mostly untrue.

People are supported for what they can do for literature, for culture, based on facets of the dominant culture. Lerato, you were supported, your whole career, I suspect, for what you could do for Whiteness. Let’s just be real here. Sometimes someone’s true love isn’t immediately apparent and I do believe this is the case for this book. You’ve spared no one, not even members of your own family it seems. Who do you truly love? Is the money you earn from those eager and willing to let you talk at literary festivals, who will perhaps buy your book, worth the kind of pain you know you’ve caused? Is it worth being known as skinfolk who ain’t kinfolk? Because you won’t be excommunicated by your blood family maybe, but the askari in you deems your black card revoked in so many people’s eyes. I’m trying to understand if it was worth it.

I’ve read enough pages of this book, which were shared on social media, to know I don’t want to buy it, don’t have to and have read just about enough. There’s nothing new here. You’re just telling black people something we’ve been told by all other groups for centuries. And no one was more willing to publish your book than folk who rarely publish books by black women. Your book also doesn’t count as a decent foray into non-fiction, it seems rather fictitious for the most part. The conversation we’re now having about this book is a sad one. We as black people keep getting thrown under the bus––your book does exactly that. It continues the tradition of harmful stereotypes, anti-blackness and pervasive gaslighting that masquerades as social commentary or advice to “my people”. That thing of saying this is where we find ourselves and somehow it’s always our fault––those who buy the five thousand (only!) copies it needs to become a bestseller in South Africa will love that. It’s telling them everything they’ve always wanted to say out loud to everyone. And in you, they’ve found just cause.

Black South Africans, at least on social media, have been deeply hurt and are shocked by your toxic words. These are the kinds of sentiments that lead to some white people in the country talking about “but Zimbabweans understand the value of work. They’re not looking for a job, just to make quick money, they want to work, unlike our fellow South Africans.” These are the sentiments white friends have told me get hurled at them on occasion by other whites looking for an outlet or same skin sympathy for their racist views. This is the mentality that was brought here by settler colonials and has never left. Meanwhile, go to any European country, go to Canada and the U.S. - and you’ll find plenty of lazy white people. You’ll find schemesters, tricksters, liars, layabouts and con artists. That you, Lerato Tshabalala, did this in a book to talk about black people in this manner shows you either haven’t travelled much or that you merely wanted to cater to a particular market that thinks this way and make bank. You’re busy translating black colloquialisms in a way that has my editor’s palm itching. You can see exactly what segment of the market you wrote this book for, for precisely this reason.

I end with something my friend said: “Lerato and Co fail to observe one simple mathematical truth. There are more black people in this country. If she were to go to Deutschland or the Netherlands, she’ll be faced with white incompetence at every corner.” Meanwhile, so many have said they see excellence or incompetence in individual people, not in the colour of their skin or their eyes.

It’s a lot to say about a book I haven’t read. And this is also part of the injury, that I’ve spent far too much time on something that isn’t even worth that.