Here's Some 1970s Psychedelic Rock From Kenya

Listen to a re-issue of the Nairobi-based band Black Savage.

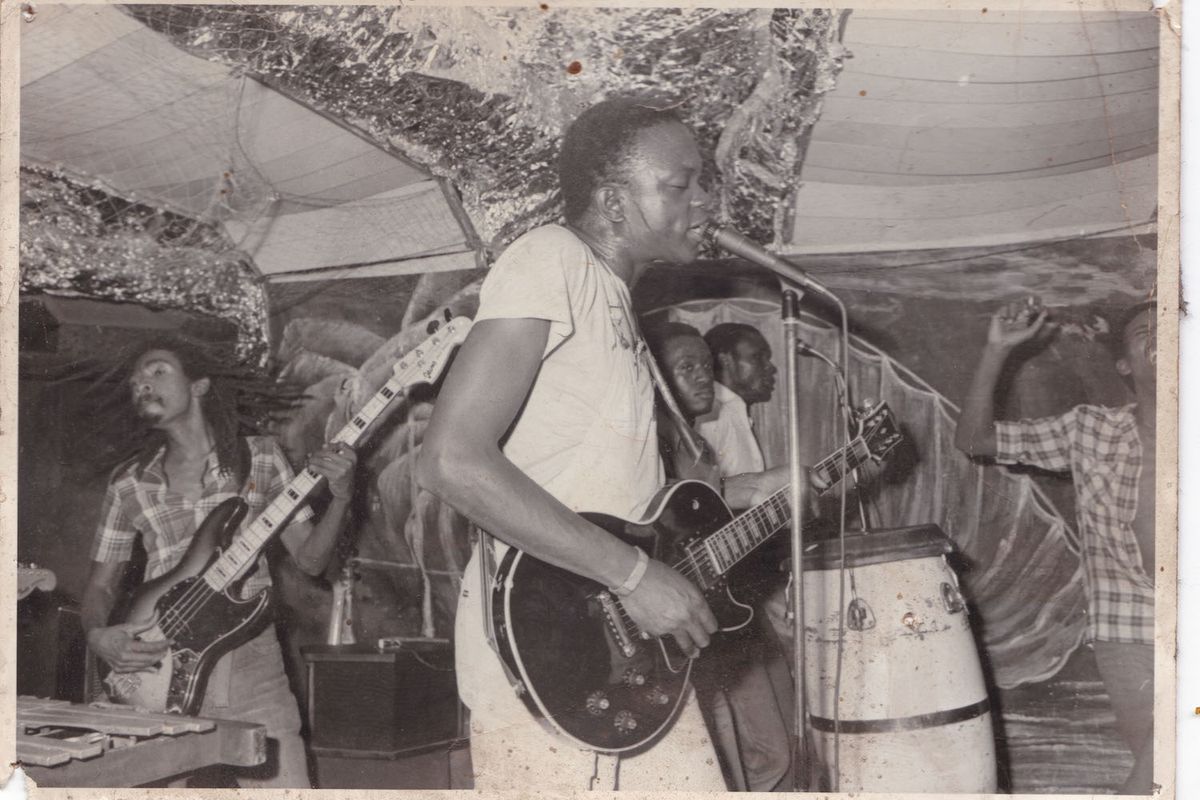

The mid-seventies in Nairobi were a time of tremendous growth. In the first decade after independence, the city's population had doubled and the economy grew at a rapid pace. Pop culture experienced a boom, live music thrived around the city and young, aspiring musicians were exposed to a wide variety of local, regional and international influences.

This was the time Nairobi developed into a musical melting pot that nurtured artists who are well remembered even outside Kenya, such as Les Mangelepa (still performing!), Matata, aor Joseph Kamaru. The music industry increased its capacity and by 1975 local pressing plants were able to produce over 10,000 records per day. Amidst the proliferation of Kenyan music being released by hundreds of bands and solo artists, some of the most interesting records did not receive proper distribution or promotion, and four decades down the line they remain un-googleable, unmentioned in discographies and generally unheard.

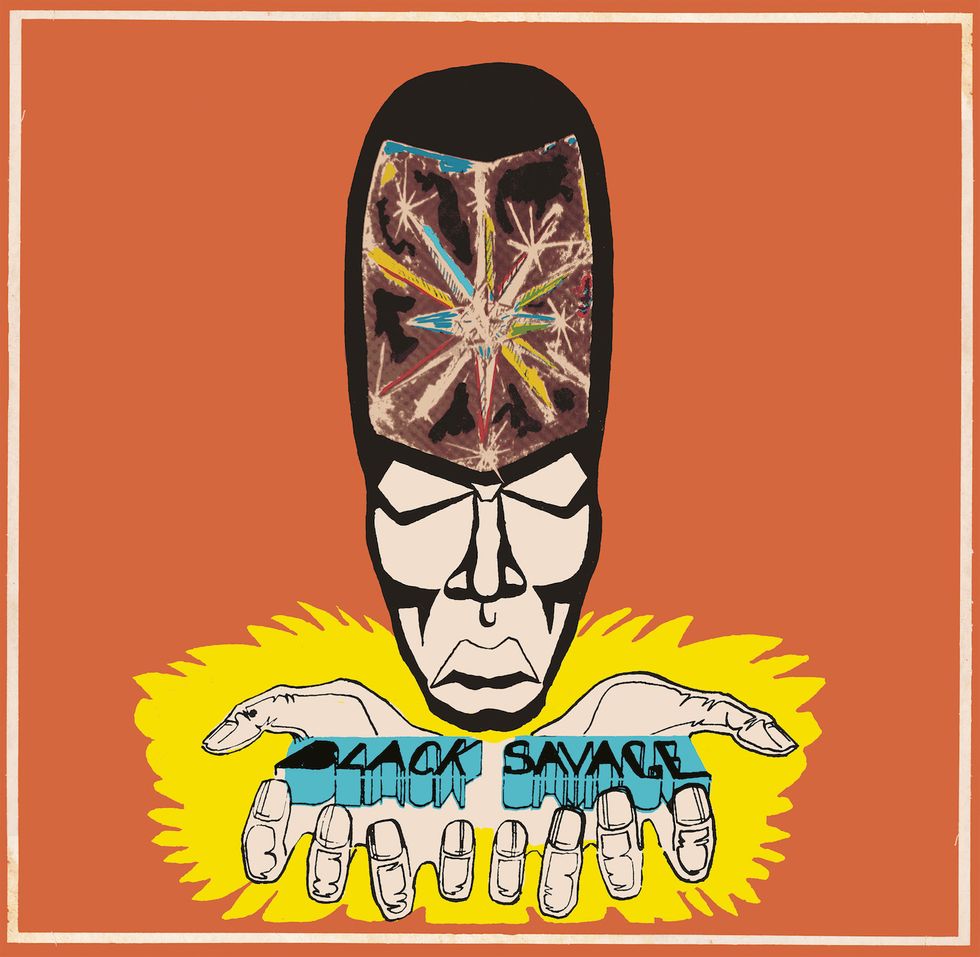

One band whose recorded output has been all but invisible until recently but who are well remembered by people who were young in 1970s Nairobi is Black Savage. Their music was released on an LP and three singles between the mid-'70s and the early 80s, and has remained out of print ever after. The early years of the band, whose members met during their secondary school years in Nairobi, are well described in the liner notes to the current reissue compilation by Afro7.

Band leader Gordon was the son of professor Simeon Ominde, who had led the reform of Kenya's educational system in 1964 upon independence, and who was teaching at Makerere University in Uganda in 1956 when his son was born. Gordon Ominde's earliest memories included Louis Armstrong's concert in Kampala in 1961, where—at the age of four—he was invited on stage and started conducting the band. Musical inspiration also came from his sisters who were singers, and from attending musical classes, although at Lenana, a former whites-only boarding school which was gradually being reformed to cater to Kenyans of different backgrounds, music education meant studying Beethoven and Mozart.

In 1973, two Kenyans of Indian heritage who had run a successful photo business since the mid-'50s, gave Kenyan music a boost by investing in a 16-track recording studio, and by acquiring EMI, Pathé and other label licenses for recording and distributing local and international music. For the next few years, the Sapra studio, record plant, tape duplication facility and colour printing business would become the go-to spot in Nairobi's Industrial Area for musicians and labels from all around East Africa. The studio was built and—as the owners struggled to find a sufficiently trained local engineer—also run by Detlef Degener, a German who had come to Kenya to construct studios for training journalists. Between 1975 when Sapra studio opened and the end of 1978 when the company went bankrupt, he recorded hundreds of bands from as far as Zambia (many Zamrock albums were produced under his guidance). Black Savage also came to record at Sapra for their debut album, which was to be released by EMI.

'Something for someone' provides a refreshing look at Kenya's musical landscape of the mid-seventies. Gordon Ominde, Job Seda, Jack Otieno and Ali Nassir weren't drawing their influence from rumba or benga but from psych and folk rock, funk and r&b. All songs were in English, and the lyrics were politically and socially aware, breathing the activist vibe of the international 'summer of love' generation. The band released three more singles. 'Do you really care/Save the savage' is two sides of semi-acoustic protest folk, 'Grassland/Kothbiro' embraces the group's Kenyan identity through the music and language, and 'Fire/Rita' (released around 1982 on the short-lived Kenyan CBS label) sounds as if the group attempts to reinvent itself—as a reggae band.

Given the rarity of the original vinyl releases, the lack of airplay and the absence of biographic info on the band, one could conclude that Black Savage ended up all but forgotten. It's reassuring that the musical paths of the band members didn't end there, though. Job Seda (who changed his name to Ayub Ogada) and Jack Otieno (today known as Jack Odongo) joined the African Heritage Band. Job then became an actor (Out of Africa), joined the UK record label Real World and scored Hollywood soundtracks. Jack went on to produce numerous Kenyan bands throughout the 1980s and 90s, and is still active as a gospel musician. Gordon Ominde continued his studies but ultimately chose for a career as a musician, and his music took him to England and to Germany where he started a family; he died unexpectedly in 2000. Mbarak Achieng is credit for composing Black Savage's "Kothbiro," which Ayub Ogada re-recorded and which ended on the soundtrack of the Constant Gardener. The memory of Black Savage as Kenya's most prolific rockers of the 1970s remains vivid in the hearts of thousands of Nairobians, and the current Afro7 reissue is a worthy first attempt at introducing their best work to an international audience.

The Black Savage compilation album is available now.

- 7 Gengetone Acts You Need to Check Out - OkayAfrica ›

- 7 Gengetone Acts You Need to Check Out - OkayAfrica ›

- 7 Gengetone Acts You Need to Check Out - OkayAfrica ›

- Interview: Mau From Nowhere Reinvents Himself - OkayAfrica ›

- Listen to Maya Amolo's New Single 'I Know' - OkayAfrica ›

- The Best East African Songs of the Month - Okayplayer ›