Emily Nkanga is the Photographer with a Human Touch

She's photographed the likes of Joeboy, Olamide, and Wizkid but the Nigerian-born artist also prides herself on images that show how people in different communities live.

Emily Nkanga is living her dream. After capturing moments and shooting memorable images for artists like Joeboy, Olamide, and Wizkid, one achievement she’s held close to her heart was when she took photos of US rapper J.Cole at a video shoot of his, earlier this year. Nkanga first came onto the radar of the Nigerian entertainment world in 2016 when she took the album photograph of Nigerian rap heavyweight, Olamide. Later, that year, her name would pop up once more, when she reenacted the same feat for the debut projects of Lil Kesh and Ycee. But Nkanga’s journey didn’t just begin all of a sudden.

“At first photography wasn’t in the plan at all,” Nkanga tells OkayAfrica. She was supposed to study Psychology but ended up going the TV/Film Production route at the American University of Nigeria. “I remember in my first semester, I made friends with a senior already into Photography and she saw the pictures I was taking on my point and shoot camera, randomly. And she was, like, oh, yeah, I should try photography since I'm gonna do TV/Film Production.' Even from secondary school, actually, I just used to like taking pictures.”

During her university days, Nkanga honed her photography skills, helping fellow students with their photo needs, and capturing events that happened at school. Her reputation grew over time. When Nkanga was undecided on what to do for her final-year project, an answer came from her instructor. “He was working on something about Internally Displaced People (IDP),” she says. “And he had a partner working on that in Syria but he was trying to do the one in Nigeria, and he said if any of the students wanted to join him and use that for their final paper, and I just jumped on it.”

That year, 2012, Nkanga defied security challenges in Adamawa, going ahead to do an expose on the unstable, stringent conditions IDPs lived in. Owing to waves of terrorist attacks happening concurrently in three main states of Yobe, Adamawa, and Borno, several communities became unsafe. With houses being demolished during attacks, residents had just one option: to take up refuge in IDP camps set up by the state governments.

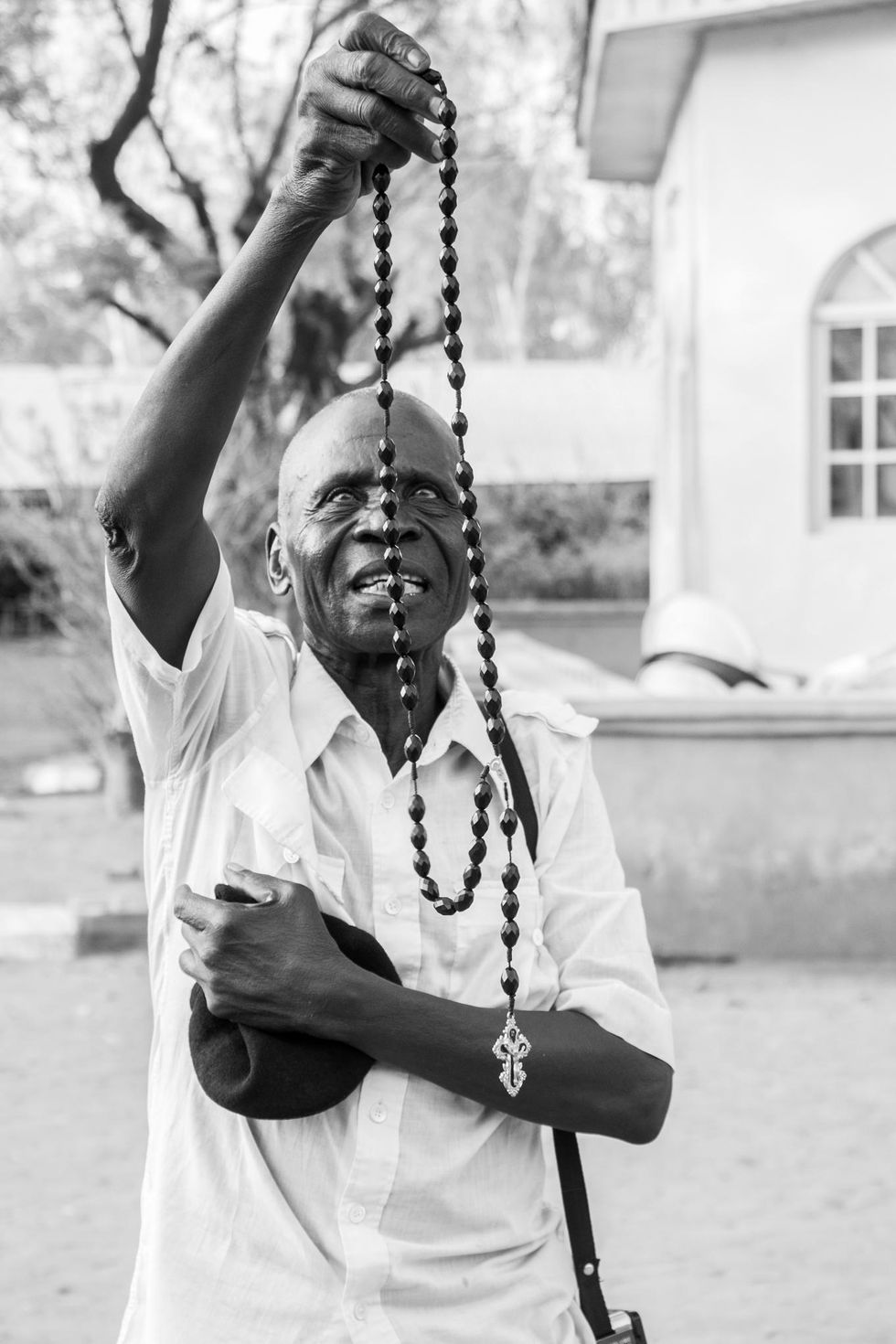

Photographing Internally Displaced People helped fuel in Emily Nkanga the desire to tell stories about the way people live.

Photo: Emily Nkanga

It was at school where she also got her foot in the door of the entertainment industry. “For my internship, I actually went to google search photographers in Nigeria. Luck came through, and I found Orbit Imagery, owned by August Udoh. I found Ayobami Macaulay on Twitter and I sent him a message, asking if I could intern for seven weeks there. He said yes and he assigned me to August Udoh. To be honest, that’s how my career kickstarted because it was during that time, a lot of musicians will come to shoot with August Udoh. There, a lot of entertainers from Olamide to Ajebutter, I met them because they came for a photo shoot.”

Nkanga has been able to shoot for celebrities and cover sold-out events thanks to her main strengths of putting herself forward and being reliable: “When I looked around, I found out that that rare ability to be reliable was lacking.”

Her major break happened one detty December. After finishing university, Nkanga met Moses Johnson, an artist manager who she’d earlier connected with when he and the artist he managed at the time, Skales, came to perform at the American University of Nigeria (AUN). Johnson had forged relationships with prominent names in the industry alongside Osagie Osarenz, an influential figure in the music industry, and chaperoned her to concert after concert. For Nkanga, there was just this zeal swelling in her. “I would do, like, three concerts in one night, taking pictures and posting on my Instagram.”

Through this process, she became Olamide’s go-to photographer for his then-yearly concert, OLIC (Olamide Live in Concert). “I took a picture of Olamide at a concert that year, I posted it and he happened to see it. He then told me to come down to OLIC. That’s how I started doing OLIC till I left Nigeria,” says Nkanga.

Even as Nkanga became a go-to name in the entertainment world, where money can take over one’s passion in an instant, she never lost her soft spot for covering human stories.

Emily Nkanga was supposed to study Psychology before she changed course to TV/Film Production at the American University of Nigeria.

Photo: Zac Gammiere

In 2017, she went on a trip to Nasarrawa to document how a community had been totally cut off from civilization. No access to clean water; no access to education for children in the community. “I’m happy I took part in that project,” she says. “It was for an NGO that went ahead to provide water for the community. Previously, that community had no access to water but the government had provided water for a neighboring community. But then that community was charging the Yeyedu people some money before they could be given water. It was insane to me.”

Any visitor to Nkanga’s Instagram page, which gives a glimpse of her select works - from photos of people in rural communities to an overhead shot of Oshodi and a popular garage in Lagos - can sense a genuine empathy for humanity. Not every creative person shares this urge to allot some of their time to do a project for their communities, but Nkanga ties it down to one thing.

Through projects like Faces of Yeyedu Community, Emily Nkanga tells empathic stories of how people live.

Photo: Emily Nkanga

“I’ve always been intrigued,” she says. “I’m always intrigued about how the next person is living, how they're surviving, how they're able to take care of things that I might not be able to take care of. Or how they're not able to take care of things that I'm able to take care of. All those things just naturally fascinate me. Or why people do certain things.”

Currently, Nkanga is putting finishing touches to a personal project dear to her—a documentary about the Ibibio tribe. It’s Nkanga’s tribe, as well.

“It's nice when people take phone pictures, yes, that's cool,” she says “But when you do it professionally, there's just something you have kept in history that at this particular time, at this certain time, this happened to Nigerians and this is what they did, this was the scene there. And in the next 100 years when future generations see it, they'd be grateful that there's a visual reference as opposed to just oral stories of, ‘Do you know what happened that year?’”