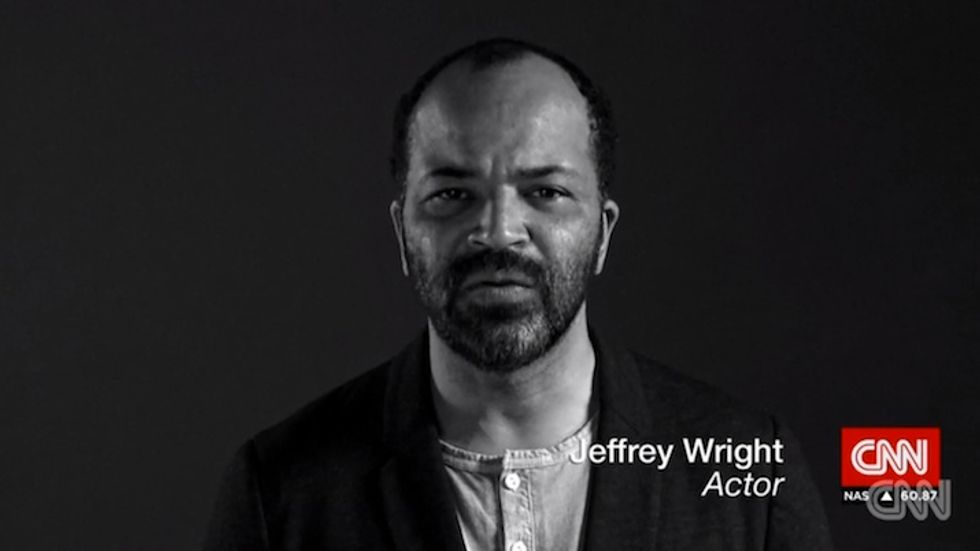

Jeffrey Wright Speaks On His #CrushEbolaNow Campaign

Jeffrey Wright speaks on the Ebola Survival Fund and his #CrushEbolaNow campaign in an interview with Okayafrica.

This Wednesday afternoon a new PSA addressing the Ebola outbreak that has focused so much of the world’s attention—and anxiety—on the West African nations of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone since late summer, premiered on CNN. The full 1-minute, 20-second TV spot (watch below) conforms to a viewer’s expectations about the outbreak and the way such crises “should” be covered in many ways; it is a star-studded affair (with on-screen cameos from movie star Idris Elba, former UK prime minister Tony Blair, OG supermodel Naomi Campbell, soul singer Alicia Keys and basketball icon Dikembe Mutombo, just to drop a few of the boldface names that appear in lower thirds) and comes complete with a hashtag-ready catchphrase: #CrushEbolaNow. It also knocks quite a few of those expectations on their sub-conscious ass.

For one, the spot features any number of West Africans who read more as heroes than disaster victims--both recognizable icons such as Liberian Nobel peace laureate Leymah Gbowee and ordinary Ebola survivors—and repeats the oddly optimistic leitmotif ‘Ebola is not a death sentence’ as often as it does its official catchphrase. For another, it arrives with some context. Actor Jeffrey Wright—best known these days for his turn as Beetee in the The Hunger Games and his recurring role on HBO’s Boardwalk Empire—is the brains behind the campaign and producer of the spot and is there to candidly spell out the campaign’s aims with CNN’s Isha Sesay.

Wright himself departs from the expectations of celebrity-causism in several key ways. Not least among these, he has ongoing interests in Sierra Leone that go back to 2001 and are completely unrelated to the present crisis (for a nuanced and expansive look at Wright’s mineral exploration company Taia Lion Resources and the various ethical and economic pitfalls it has placed in his path, see “Jeffrey Wright’s Gold Mine,” Michael Christopher Brown’s excellent piece for the NY Times Magazine this past January).

We took the opportunity to get Wright’s thoughts on the crisis, what’s wrong with the way it's been covered until now and the future of the region...

Eddie for Okayafrica: Tell us why this crisis is so close to home for you.

Jeffrey Wright: I first went to Sierra Leone in 2001--during the war--and I’ve been involved ever since. I set up a company and a foundation that work together for developing a natural resource project there but in close partnership with local communities, trying to create a mining company for the 21st century. So we’ve been operating in the Eastern part of Sierra Leone in the Kailahun district since 2003.

Kailahun was the first district in SL to be touched by the Ebola outbreak. We operate largely within a community that is situated directly on the Guinea border. When we first got news of the fatalities from Ebola in Guinea we began having regular conversations with the paramount chief--who is essentially the governor of the chiefdom that we work most closely with, the Penguia chiefdom--and other representatives of the community, to determine what the conditions were there and what they might need from us in terms of staving off transmission among them. We also spoke to representatives of the World Health Organization, to understand what they thought would be the best means of early intervention.

In I believe late May, Early June 2014, we became alarmed because when got news that a doctor had become the first person to succumb to the disease within Penguia--apparently, he was infected by a visiting practitioner nurse from outside the community--and passed away. We then immediately coordinated with the chiefdom authorities and pushed monies through Taia Peace Foundation over to them so that they could purchase--I think at that time it was 120 liters of chlorine and a couple hundred boxes of medical gloves--and they organized the distribution of those items themselves. Subsequent to that we pushed some more funds over to put up a hundred public wash stations within the chiefdom. All the public gathering places were to be equipped with a disinfectant station.

So I’m not certain if it was a result of the organization within the chiefdom and community or whether we were early or whether we were lucky or some combination of the three. Or it’s the result of theyre being an isolated community among the isolated…but they’ve experienced no fatalities from Ebola since that first doctor passed away.

OKA: So tell us exactly what’s the mission with this PSA--and why is it so important to reshape the way the crisis has been covered in the West so far?

JW: The worst aspect of the narrative to this point, I think, is that it has further served to do what we too often do when we view the people of this region--and that is to rob them of their dignity and their strengths and devalue them. With this PSA—understanding that people are facing some extraordinary challenges—we are trying nonetheless to celebrate their strengths and their beauty and their dignity in the face of these challenges and remind people that there are not only Americans and Europeans who have survived this thing but there have been heroic Sierra Leoneans, Liberians and Guineans who have survived as well--and they survived because they managed to get early and proper medical treatment.

OKA: To play devil’s advocate for a sec---I don’t think there’s any question that the way the Ebola crisis is being depicted is true of a larger syndrome around representation of Africa in the Western media: stories are framed with a sense of alarm or fear and there is also this persistent trope of victimization, images or narratives of people who need to be saved by Western intervention. But are you concerned at all that by trying to counter that in a moment of crisis, that you may undercut the urgency of the message? Is it possible those narratives, troubling as they may be in their repetition, sound a louder alarm or activate people more effectively than a more nuanced message?

JW: If we are to respond and respond effectively we’ve got to understand what were looking at. And I don’t think we’re most effective when we’re operating from a place of fear. Or when we’re operating from a place of dehumanization of those we hope to assist. We think we framed the narrative that explains through an optimistic lens that engagement Will. Be. Successful. We want to emphasize that: your engagement, your deployment of resources will be well spent, will create greater survivor numbers.

So, no, I’m not concerned about that—I think part of the reason we're having this conversation is because of the continued victimization narrative that’s delivered around people like the people who live in this region—that’s why we need to have this conversation, because in order to convince people that the folks over there are more than victims, are willing economic partners who can bring something to the table with equal value to what we can bring to the table…if we can have that conversation, then we can start to create the economic and social strength in these areas that will make these type of conversations pointless. I think we balanced the message in such a way that it remains effective.