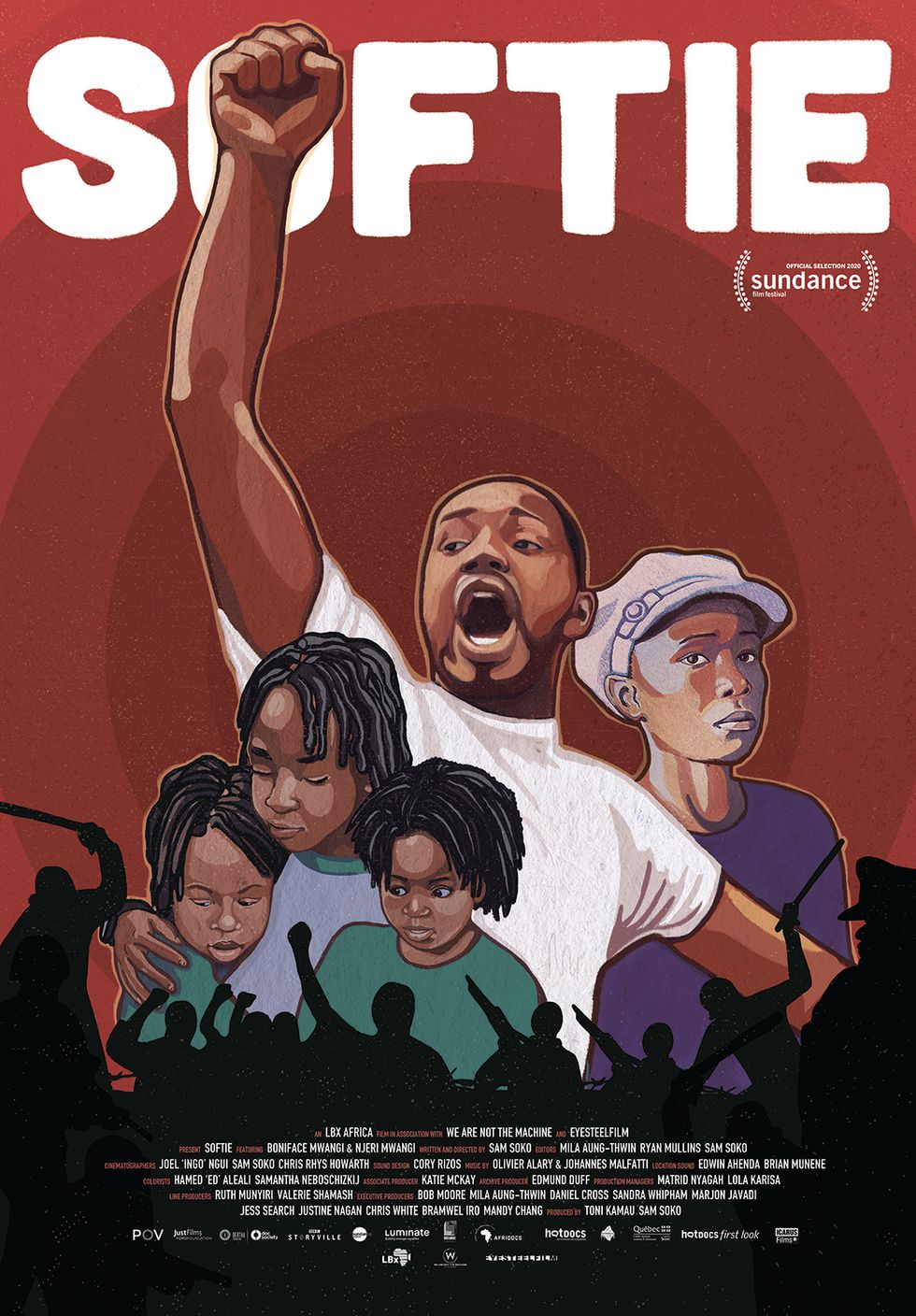

Interview: Sam Soko is the Kenyan Director Behind Sundance Hit, 'Softie'

We meet filmmaker Sam Soko who has made a stirring documentary about the Kenyan protest leader Boniface Mwangi

Kenyan anti-corruption activist Boniface Mwangi is the main character of Sam Soko's film.

Filmmaker Sam Soko didn't intend on making a documentary about Kenyan photojournalist-turned-politician Boniface Mwangi.

The original idea he had was to make a manual of sorts, a short video guide, on how to protest, the do's and don't's. Soko, himself an activist artist who cut his teeth convincing friends to let him create political music videos for their apolitical songs, knew Mwangi's experience on the streets both photographing protests and staging them meant he had a lot to share with others.

But then came the blood. A thousand litres of it, to be precise. And the pigs. Dozens of them, with words like MPigs written on them. Like the graphic photos Mwangi had become known for taking—it was a sight you couldn't look away from. It was a protest Mwangi organized, in 2013, to decry corrupt members of the Kenyan parliament who had decided to increase their salaries, 2 months after taking office. And at his side, through the thick red liquid of it all, was Mwangi's wife, Njeri, ready to be arrested with him.

"Once I was witness to his relationship, I started seeing him as a family man," Soko tells OkayAfrica. "Because he's planning a protest and all, but when you look at the footage, you start seeing the kids and you start seeing Njeri. That's when it started hitting me, in the sense, that she was with him in such a crazy space."

Soko met Mwangi through the creative and activist hub he created called PAWA 254, as they became part of the groundswell demanding democratic reforms in a country still left scarred from the division sewed between Kikuyu and Luo people by British colonizers. "We had a new Constitution at the time, and there was this hope that we finally could picket without being tear-gassed or being beaten, Like, our civil liberties could be held up." Instead, the government strengthened its police force into a notorious organization condemned by human rights activists. "That's very salient in the film," says Soko. "If you see how the police dress, for instance, at the beginning, it's very different; they become more militant towards the end."

Soko's debut feature-length documentary, Softie, which became the first Kenyan film to ever premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, earlier this year, is at once a love story between Mwangi and his wife and their three children, but also between Mwangi and his beloved Kenya, under president Uhuru Kenyatta. Central to the film is the tussle between how these different loves bump up against each other: what comes first — love of country or love of family?

We spoke to the Nairobi-based director about making the film, which opens in virtual cinemas, starting this Friday, September 18th.

OA: Early on in the film, we learn how steadfast Boniface Mwangi is — he talks about being willing to die for the ideals he believes in, which made me think of Nelson Mandela and his Rivonia Treason Trial speech. Boniface is someone in the present day who still shares this belief?

When we were working on the edit, and kind of crafting and thinking about what the story was going to be, something that we found that was really, really interesting is, with a lot of the stories, like the story of Nelson Mandela, you'd never see the other side. That's something we see later, up ahead, as a retrospective. We'd hear about Martin Luther King and then we'd read about Coretta Scott in, I think, 1990, like, 'Oh, this his was her struggle.' That sort of thing. But for me, Boniface and Njeri represented a present day reality struggle that showcases what Mandela was going through, what Martin Luther was going through. That was kind of like unravelling the curtain; when you see Martin Luther marching, Coretta's at home, trying to help their kids do their homework. And this is the reality.

OA: And the film poses that question of love for your country versus love for your family, and which one should come first?

Exactly. They see it in different ways. Boniface sees it that if you improve the country, you improve the lives of those who you love. Njeri's like, you have to have your family's back first. And that means everything else comes second. And she's right; she's not wrong. And he's not wrong.

OA: The film really is privy to some really private moments in Mwangi's life — how did you gain his trust?

When we started filming the short video, he was really involved with the protests, and we started doing the protests with him. So we were—quote, unquote—in the trenches with him in the protests, and somehow that's how he kind of welcomed us to his home. When you've been with someone in the streets, and you're tear-gassed together more than once, you already have a common bond. But then I started developing a relationship with him that was beyond the streets. Just checking up on him and asking, what's going on, what's taking place? That sort of thing. I think it took a while. And I think even from Njeri, we kind of developed a kind of camaraderie that was separate from my relationship with Boniface, because I would actually be like, 'Hey, he said that, how does that make you feel?' And not necessarily on camera. But over time, he kind of accepted us to be there with a camera. At some point, I kind of felt like they were talking to me, and not necessarily the camera; like, the camera is kind of this thing that's there, but not there. That kind of trust, again, was built on a respect that I have for them and their values and what they're doing. I think that's something they saw. It made them trust me with their story and trust me with their family.

You're the director of the film, but you're also producer, writer and cinematographer. Did Boniface's own style as a photojournalist influence you in any way?

The film has more than one cinematographer, and a lot of my cinematography is within the intimate moments, because that's when they would only engage with someone they trust. But him being a photographer actually, to a point, made the work a bit hard because he's constantly looking at how you're doing it. He's in your face about the angle. He's like, 'Hey, why are you standing there, you should be there.' But in some places he did help 'cause he's been filming in the streets and filming protests for a very long time. So when you're there filming, he'll easily tell you, 'Dude, don't stand there. They're about to start tear-gassing. Go to the other side.' And it's weird, when you're on the other side and you're filming, and all of a sudden you see tear gas, you wonder, 'How the hell did he know?' You do that 234 times and you start knowing yourself, 'Oh, this is how,' and he was really helpful in that sense.

I can imagine that filming during the protests must have been one of the big challenges of making this film but what else did you struggle with? There were death threats for Mwangi, did that happen to you as well?

It's so funny, when you're filming and when you're in the protests, it's adrenaline talking. So you're not really thinking about whether you're going to be okay. This one time, I got arrested because the cop said I was a spy for the protesters. [We had everything] from cameras breaking to sound equipment messing up, but when it became a more political story, with death threats, it became scary even for editing the film. Because you don't know who's watching you. This one time, I was with him in the car, filming, and we were being followed. So we kind of had to be very careful who we are telling about the story. It was a very deep secret that we were making this film and there are people who are watching it now asking, 'How could you keep this from us from all these years?' Because we had to do that. Especially when the family was in the US. We had to do that for the sake of safety for him, Boniface, for his family but also the film team. I remember doing the pitches with different names. But then we were also lucky that we had our co-producing partner in Canada, Eye Steel Film, so they were able to house the edit there. I went to Canada to edit and that kind of also gives you a kind of freedom to think and work and create. That was the reality, and now I think we have PTSD from the film. I can't film another protest. I'm sorry. I'm out. Like, it tapped me out.

There are similarities to the Black Lives Matter protests here in the US, against police brutality and violence but the slogan takes on a different resonance in places like Kenya, where the police force is particularly heavy-handed. How do you see these protests as being similar but also different?

There are two things that you learn with the film. One, our voices can never be silenced. They will try, but I think humanity is like a pressure cooker. The more you boil us, the more you put that heat, the more explosive we become. And through people like Boniface's life, you see that there are human beings who exist, who do extraordinary things.

The other thing is the idea of activism doesn't necessarily just speak to the person who's on the street. It doesn't necessarily speak to the person who's holding the placard. An activist is someone like Njeri and her life, and her family. And Khadija [Mohamed, Mwangi's campaign manager]. She's such a strong and powerful activist in her own right. She was Boniface's campaign manager for free. The work they did was so powerful. And you have these other people in the background who are doing such incredible things. The sum total of what they've done is [to] instigate… We have an election next year, but I am so sure that we are going to have so many candidates who are going to be like, 'We want you to donate to our campaign. We have these values and beliefs; this is what we want to do.' That is how we need to go about change or add on to the conversations of change.

The same thing that's happening with the Black Lives Matters movement. Yes, there are people going to the street and we should keep going to the street. But we need to push people to engage in policy and make sure these policy changes are made.

We need to stand for what we believe in, as filmmakers in spaces where we feel oppression exists. Like the rules that have come out with the Academy Awards, these are rules that should be celebrated because they add on to that conversation of diversity and representation. All these things—that sum total—is what makes the difference. It's going beyond the streets and going beyond our Tweets, going beyond our Facebook messages, making films and sharing films. We just need to keep pumping up the volume, keeping the heat up, keep pushing. It's gonna take a while, but we'll get there.

That's where you as a filmmaker come in—this film was the first Kenyan film to get into Sundance, where it won a special editing prize.

There's another film I'm producing and, and, yes, I had my film at Sundance, that's great. But there's this other filmmaker who's making another film, and it's so cool, and this is the thing—we need to keep bouncing off this energy and this light and this vibe, and just keep pushing and making sure that the wheels keep turning. That's what we're all about.

How do you renew your strength, as a filmmaker but also as a Kenyan and as an African?

Being a Kenyan is hard. I think being an African is hard. Like, it's hard. There's a line I heard Boniface say once: 'I love my country, but I am afraid of my government.' But the way in which, personally, I find energy is when I meet new filmmakers, or you know, people who are like starting out and they want to make films that sound totally crazy. And they believe that they can do it. And I'm like, 'yes, yes, keep going!' We are planning to do a premiere. We have not confirmed the date yet but we're thinking it's around going to be early October in Kenya, because Kenyans haven't watched it. The government gave us an adult rating.

This is the same government that banned Wanuri Kahiu's Rafiki because of its homosexual theme…

Exactly, that's what we're getting but the lemonade that we've made out of all this is, 'Guess what? This is cinema!' We're going to take it to a cinema. People are going to come to watch it in a cinema or watch it at home or watch it in the best way possible. And the people who've watched it have appreciated it as a film and a story, and their story. They've seen a reflection of themselves. That gives me so much joy because the Kenyans who've watched it, when they give you feedback, they say, this is truth; this is our truth. And they don't see just an activist. They see a couple struggling with love. They see our history in the last 10 years. And they're like, 'What the hell, we lived this?' and they see the things that are unresolved — and many things are unresolved. Seeing that reaction gives me so much strength and hope. But it's hard. It's very hard. Because, you know, you have to wake up and see the policeman getting a bribe. And you're like, 'Homie??'

Watch the trailer for Softie here.

Softie | Official Trailer | A film by Sam Sokowww.youtube.com

- The Face Of Kenyan Protest: Boniface Mwangi On Corruption, Land ... ›

- Kenya's Boniface Mwangi Talks Activism, Shading the Deputy ... ›

- Kenya's Courts Have Failed the LGBT Community Once Again ... ›

- Kevin Mwachiro, journalist, queer activist, podcaster [Kenya ... ›

- African Films at Sundance 2013 - OkayAfrica ›

- These 4 African Directors Are Set To Premiere Feature Films at the ... ›

- Kenyan Court Interdicts President Uhuru Kenyatta's Illegitimate Move to Change the Constitution - OkayAfrica ›

- South African Director Oliver Hermanus Remakes a Classic - OkayAfrica ›