In Conversation: The Director of The Museum of Black Civilizations

Hamady Boucoum talks about the return of Africa's looted treasures and how the museum is subverting expectations

In his novel Foreign Gods, Inc., critically acclaimed Nigerian novelist, Okey Ndibe, tells the story of Ike, a New York-based Nigerian cab driver who sets out to steal the statue of an ancient war deity from his home village and sell it to a New York gallery. Driven to this point of desperation by a series of unfortunate events in his life as a migrant, Ike hatches a plan to steal this statue that, in modern times, he believes, means little to his people—but one that could fetch him a pretty penny if it gets into the hands of collectors in the West.

I could not help but contrast this image with that of me walking into the new Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar, flanked by busloads of Senegalese school children eager and excited to see artifacts from around their continent, in their own continent. The fact that African art did not have to leave the continent to be valued is perhaps the most vital aspect of this fabulous new museum.

The museum draws its architectural inspiration from the inner atriums of the homes in the Casamance region in the South of Senegal and the Great Zimbabwe. These houses consist of rooms built in a circle with a round and empty patio in the middle that is used for catching rainwater. This design creates a tunnel of light reaching the center of the building. In the center of the museum is a 40 feet tall steel baobab tree sculpture by Haitian artist, Edouard Duval-Carrié. Inside, the museum is broken down into four sections: The Cradle of Humanity, Continental African Civilizations, Globalization of Africa and Africa Now.

I meet Hamady Bocoum, the museum's director, in his office. He's a seasoned archeologist, researcher and erstwhile Director of the African Institute of Basic Research in Dakar and who speaks passionately about the issues. The work behind the museum, he tells me, began in the 1960s at the encouragement of Senegalese president, Léopold Sédar Senghor—in 2015 the plan was revived and it opened last year with the mandate of being for all people of African origin worldwide.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

You've said that in the creation of the museum you found it easier to articulate what it shouldn't be rather than what it should be. What is the museum not?

Some of the things we agreed on is firstly, that this would not be a museum on ethnology. Ethnology to us is about westerners looking at Africans—for example, the Masai people are a nomadic… the Hausa are…—rather than us looking at ourselves. The second thing was that this museum would not be an anthropological one. This is because anthropology is what was used to rationalize the concept of race—a concept that has had devastating effects for those outside the power structures, especially black people. Anthropology allowed the enslavement of black people to be legitimized. The third thing we agreed on was that this would not be a subaltern museum.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, an Indian scholar, literary theorist, and feminist critic describes subaltern in the postcolonial context as follows: "Western intellectuals relegate other, non-Western (African, Asian, Middle Eastern) forms of "knowing", of acquiring knowledge of the world, to the margins of intellectual discourse, by re-formulating these forms of knowing as myth and as folklore. To be heard and known, the subaltern must adopt Western ways of knowing, of thought, reasoning, and language."]

Our determination to not be a subaltern museum was the reason we did not model the museum on any museums such as the Louvre, Musée d'Orsay or other well known museums. We wanted the museum not to be held to western standards in terms of how it should look. Our museum would traverse the whole story from the origin of mankind to contemporary times.

The overarching sentiment was that the story of black civilizations is a story of humanity. The Manden Charter of the Mandingo people of West Africa was created in the 13th century making it one of the oldest constitutions in the world—albeit oral. It has its first law as "All life is equal." Africans never placed people above animals, trees, lakes or forests. In Africa, when we prayed or ask for forgiveness before killing an animal for food, we did not do this out of superstition. We did it because of our view on humanity.

Africa was the locomotive of human civilization for over 7 million years ago. Colonization was around 550 years of that time period. We want the museum to be representative of African history in its entirety.

What's your favourite story behind how artifacts came to your museum?

When the British destroyed Benin city in 1897 they stole all the masks of the Oba People.These are on display in the British museum. What they didn't know was that there were two copies of each of the masks. The others were with the queen mother who lived outside of Benin City. When she heard that her son, the Oba (King) had been imprisoned, she hid all these masks. We have her collection here on display. They have been available for display in different parts of the world. They recently came from Miami and we will be sending them back shortly to Nigeria.

What has been the reception of the museum so far? What has surprised you?

It's been overwhelmingly positive. When we opened the museum in late December 2018, we had 700 items on exhibit. Only one month later we already have 1,300 items. Other museums are eager for us to display their items. I expect that in a year we will have between 4,000–5,000 items on display. It should be noted that we don't own any of our items. They will always be loaned from different museums worldwide. The black diaspora worldwide has really mobilized to make sure that we will always have diverse and engaging content. 80 percent of what is on exhibit right now comes from outside of Senegal—other African countries and black diaspora. The lowest number of visitors we've had on any day so far is 350 . We are averaging 500–600 visitors every day with having even reached 800 visitors on one day.

How does the museum plan to engage with the diaspora?

Even from the inception process we have been engaging with artists and museum curators from different parts of the black diaspora including Cuba, the US, Brazil etc. The exhibits at the museum will keep changing—with the Cradle of Humanity remaining as the only permanent one. All the other exhibits including the one on contemporary art, will continually have changing themes and displays that engage with content from black diaspora. This is not the museum of Senegalese civilizations or of African civilizations. It is and will continue to remain, the Museum of Black Civilizations. Each time we change the exposition, we will aim to be as representative as possible. The current exhibits will all be changed in September—except for our permanent exhibit—The Cradle of Humanity. The exhibit on contemporary art will be changed every 6 months.

Given current calls for repatriation of Africa's looted assets, what role do you think the museum will play in this discussion?

We cannot let those who looted our assets then tell us what we should do with them. Restitution needs to happen with the knowledge that the looter has no right to decide what happens with items that were never theirs in the first place. If I stole your ring and you asked for it back, how can I then tell you that you need to first let me know where you will put it, before I give it back to you? No one has that right!

If people get their artifacts back and want to put them in a sacred forest, that is absolutely their right! When these objects were stolen from the continent, we never said that they were artwork to be displayed. Some of these artwork includes severed skulls that were taken during a time of oppression, colonization, violence and the subjugation of Africans. How can anyone dictate to us what we should do with our looted objects once they are returned?

The return of our looted assets should not be dependent on us having space to exhibit them. It should be based on the fact that they belong to us and were looted.

What are some of your favorite exhibits at the museum? Why? What is it about them that stands out the most to you?

The sculpture of the giant baobab tree that is in the middle of the museum. It was done by the Haitian sculptor, Edouard Duval-Carrié. It's location in the center of the museum shows that the diaspora is at the heart of the story on black civilization. He's one of the greatest sculptors in the world. All the work was done in Haiti, but the sculpture had to be installed piece by piece in the museum given its massive size. This metal art form—of using cut pieces of iron is one that has been perfected by Haitian sculptors and has its origin in the slave plantations. The iron workers who were in the plantations were responsible for making all the iron tools that would be used by other slaves. When they had leftover iron, they would use it to use it to make decorative items. The beloved tree of life is of great cultural, spiritual and historical significance in Senegal with some of the trees being between 1,000—2,500 years old and having more than 300 uses.

What would you consider as success for this museum looking back a few years from now? What would you have hoped to attain?

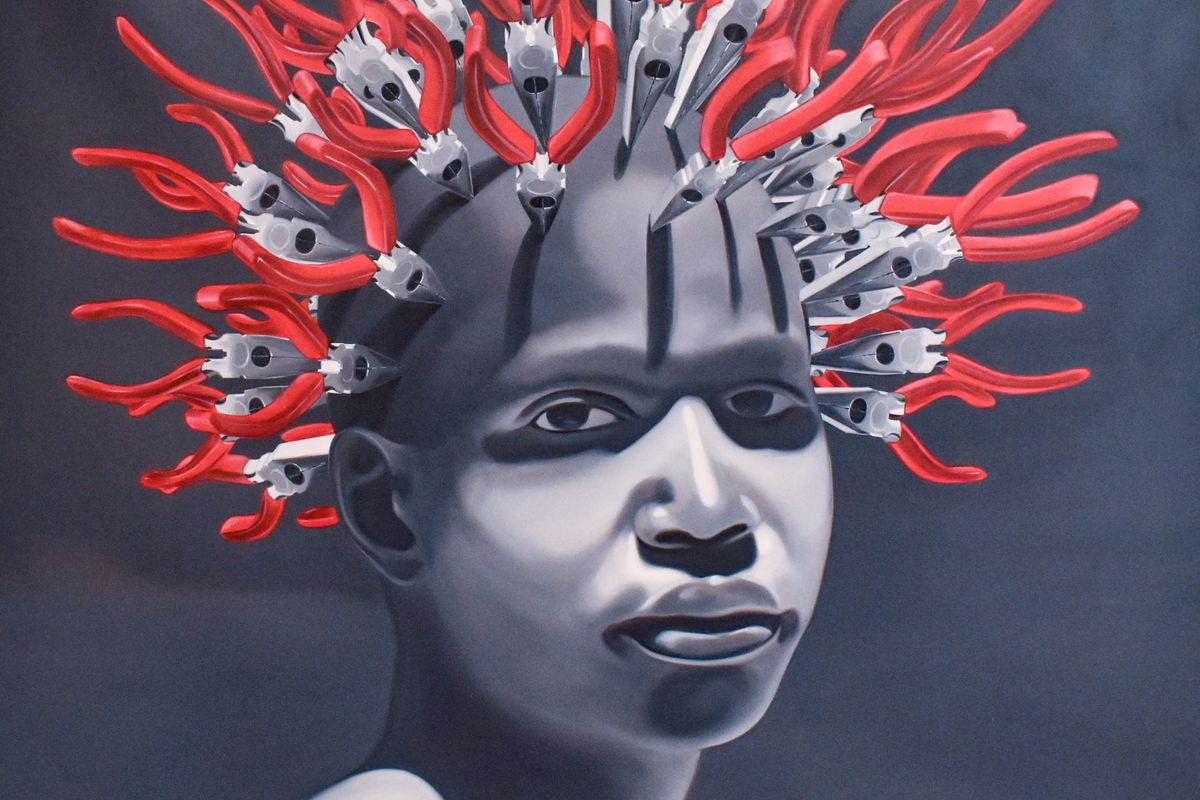

That black people worldwide will engage with this museum and that it will serve as a space where we can have dialogue among ourselves, but also with other civilizations. This is the reason that we have a current exhibit on "Dialogue of masks" that not only features African masks, but also Indian ones, Native American ones etc. We want to show that the story of black civilizations is the story of all humanity.

- Senegal Urges French Museums To Return Looted Art - OkayAfrica ›

- Senegal Opens Museum of Black Civilizations—One of the Largest ... ›

- Scottish University Set to Return Looted Nigerian Artefact - OkayAfrica ›

- A Stolen 18th Century Ethiopian Crown Has Been Returned from The Netherlands - Okayplayer ›

- Senegal opens new art museum honoring black civilization | Reuters ›

- Senegal's Museum of Black Civilizations Welcomes Some ... ›

- Museum of Black Civilisations aims to 'decolonise knowledge ... ›

- Sprawling Museum of Black Civilizations Opens in Senegal | Smart ... ›

- Senegal unveils Museum of Black Civilisations - BBC News ›