In Conversation with C.J. Obasi on His New 'Kick-Ass' Supernatural Thriller Inspired by Mami Wata

The award-winning Nigerian filmmaker wants to challenge dated stereotypes of African women with this new project.

Award-winning Nigerian filmmaker C.J. Obasi followed-up his critically-acclaimed guerrilla debut feature Ojuju (2014), and sophomore effort O-Town (2015), with an Afrofuturistic short film based on award-winning author Nnedi Okorafor's short story Hello, Moto. Currently touring the international film festival circuit, the short film—titled Hello, Rain—follows a woman who discovers witchcraft in science, and science in witchcraft, when she creates wigs for her friends that give them supernatural powers. The story tackles individual and societal identity, in a fairytale that unfolds via a blend of witchery and technology.

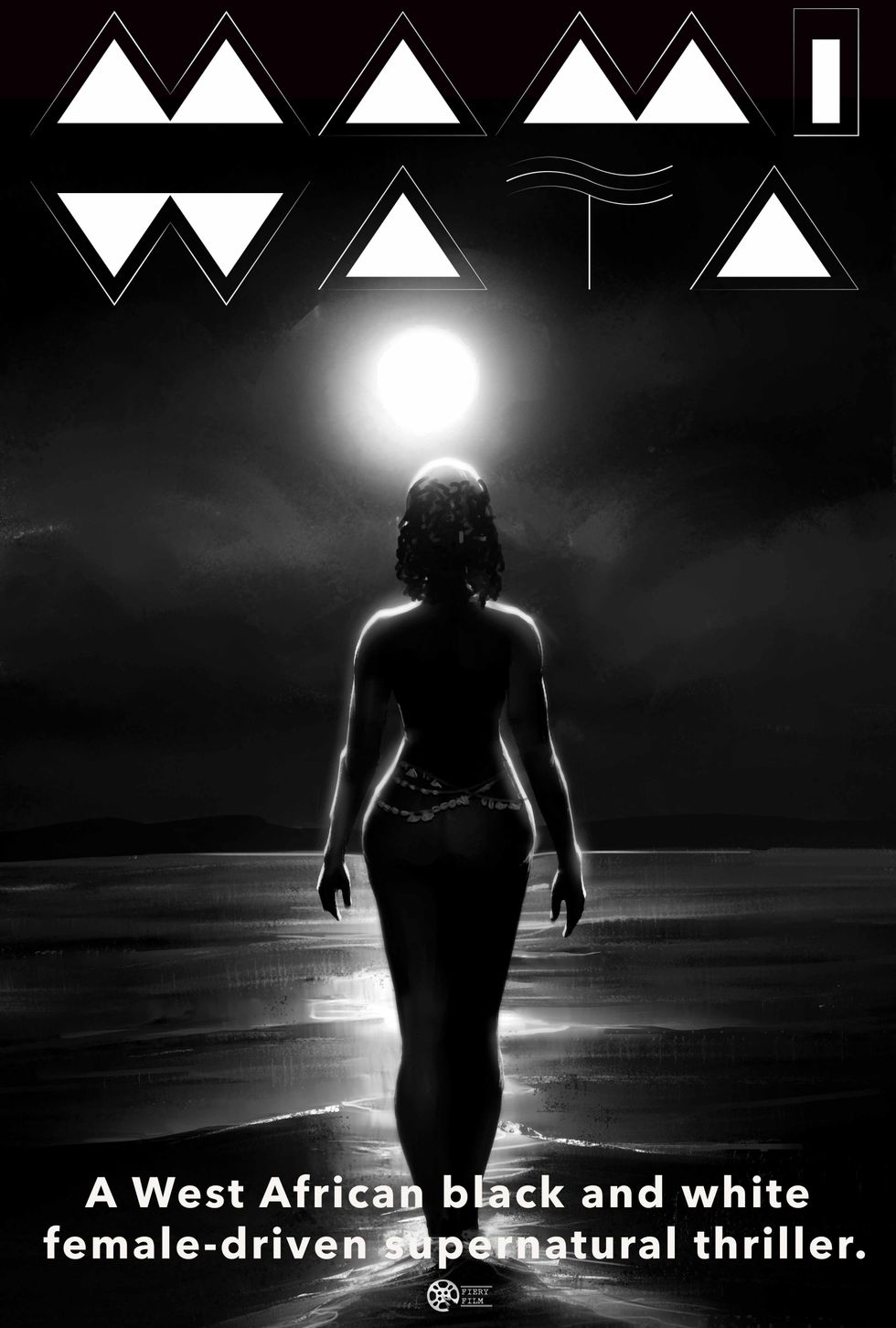

Staying within the world of the supernatural and female-centered narratives, the prolific Obasi—who first caused an international stir with his zombie thriller Ojuju, set against a contemporary Nigeria backdrop—looks to do the same with his next feature film, in what will be another renegade take on a familiar genre, inspired by the age-old West African legend of love and sacrifice known as Mami Wata (Mother Water). Summarized by the filmmaker as a "kick-ass, female-driven, black & white supernatural thriller," the official synopsis of the film reads:

When Zinwe visits her late grandmother's village—a small rural fish village, she must confront her true spiritual destiny, and save her people from the hands of the ruthless and violent Sergeant Jasper, to usher in a new age of blessing and prosperity.

The Mami Wata folklore has taken several unique forms across Africa and its diaspora—primarily in the Americas—as there are a variety of interpretations of what the deity truly represents. In some instances, she's reified as a good spirit, or a mermaid, whose presence in a person's life is a sign of good fortune. Others will describe her as cunning and seductive, or protective yet dangerous, a snake charmer, or a combination of all of the above.

And just as varied are descriptions of her physical being—having long dark hair, very fair skin and compelling eyes; or, in other depictions, she has short hair, and can even be bald. She may appear to her devotees (in dreams and visions) as a beautiful mermaid, complete with a tail. She is also said to walk the streets of African cities in the guise of a beautiful but elusive woman. And the colors of the clothing she most often wears are either red and/or white.

Promising a film that will "overthrow stereotypes about black women, and black cinema by challenging old narratives and revealing new visual possibilities," Obasi's Lagos-based Fiery Film production company will produce Mami Wata starring Lucy Ameh, Ogee Nelson, and Wale Adebayo, with Obasi directing from his own script, and Oge Obasi producing.

Other notable behind-the-camera talent attached to bring the project to life are AMVCA award-winning costume designer, Obijie "Byge" Oru, as well as AMVCA-nominated and BON award-winning make-up artist, Adefunke Olowu.

Mami Wata will be shot in the outskirts of Lagos, in the villages bordering Nigeria and Benin Republic, and near the Atlantic Ocean.

Given the superstition around and taboo (to some) nature of the mythology central to the film's narrative, it's been a challenge attracting the necessary financing required to bring such an ambitious concept to the screen. Hence, the filmmakers have launched an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign to raise $120,000, in anticipation of a likely fall 2018 principal photography start date.

I spoke briefly with Obasi about the project—its origins, his decision to film in black and white instead of color, telling a woman-centered story against the #MeToo backdrop, amid a rise in attention given to stories about women, and more.

An edited transcript of our exchange follows below.

Tambay Obenson: Mami Wata folklore is not only revered in Nigeria, but also throughout much of West, Central, and Southern Africa, and the African diaspora in the Americas, which means that there isn't a singular, universal representation and understanding of her. Why did you select this particular mythology as the basis, or inspiration for a feature film?

C.J. Obasi: It just hit me. The image of this mermaid goddess in stunning black and white just hit me, and I could see it very clearly. Usually with film projects, you sieve through different ideas and then one just sticks out. But with "Mami Wata," I wasn't even thinking about it. It just happened, and I haven't been able to shake it off. But I like the fact that in Africa and the African diaspora there are different ideologies and beliefs associated with her. I like that over the years it has become more than just a traditional belief, but an idea expressed through a people's spirituality. In West Africa, we have countless folklore, but Mami Wata is one of the few that has a tangible and very organic presence in our daily lives. And It makes you wonder, if colonialism didn't happen, or if it happened, but certain African worlds where excluded from its influence, what would such a society look like? How would I represent that world visually without pandering to stereotypes. Now those questions really spurred me into action.

Since the deity is of deep spiritual significance and even sacred for some within the diaspora, rooted in ancient tradition, do you concern yourself with how your modern genre interpretation of the folklore might be received by those who are more orthodox and traditional?

No. The only people who will have a problem with my interpretation are the church folks; you know, those who think anything even remotely traditional is devilish or something, yet don't have any issues whatsoever buying "Little Mermaid" merchandise for their kids. Anyone who is truly African orthodox will appreciate how we'll uphold core African values and spirituality. At least they should. Because that's exactly what we're doing.

What led to the decision to shoot the film in black and white, instead of color? It's a curious, bold approach, especially in 2018, and for a story that I would immediately visualize as one that would benefit from color. Although I think shooting black and white might help distinguish the film.

I'm a student of all cinema. I have favourite films that are both colour and black and white, but as a personal visual aesthetic I've always leaned towards colour, which was weird to me when I realized that I could not visualize the film in colour. When I picture Mami Wata, I picture deep, contrasted, ultra-stylish black and white, accentuating ethereal landscapes, ocean waves, and gloriously beautiful dark skin. That's what I see. And I absolutely agree that black and white will distinguish the film. There really is so much content being pushed out into the world, so as a filmmaker you immediately want your work to stand out visually. I just believe that making a genre work of this nature, you want to really push the limits of what visual storytelling can be. The work demands that.

I assume you're shooting digital, given your budget. Your stated approach to a film that is "... deep, contrasted, ultra-stylish black and white, accentuating ethereal landscapes, ocean waves, and gloriously beautiful dark skin..." immediately tickles the imagination, as I can visualize how dramatically interesting it could look if you were able to shoot it on some high contrast, black & white 16 or 35mm film stock, and really take advantage of what celluloid has to offer in terms of playing with lighting and shadows, as well as in post-production. Although digital cameras today are almost as comparable.

That would be my ideal choice—shooting on black and white film stock. Alas, the budget, as you said. Even without the issue of a lower budget, there's also the fact that we don't have any film processing labs in Nigeria. So literally, we would be filming blind, without seeing any of our dailies at all, which you can't really pull off, again, without an adequate budget. So the digital option is indeed a saviour for many of us in these cases. In as much as we would love to shoot celluloid, we make do, and there are hacks to get us pretty close to that film texture. It's never the same, but it'll still be pretty sweet. I promise.

When you say that the film will "overthrow stereotypes about black women, and black cinema by challenging old narratives and revealing new visual possibilities," can you further expound on that?

I'm trying to answer this question without spoilers. What I mean by that is, the entire story is driven by strong female characters whose story arcs are not dependent on their boyfriends or husbands, which is something we can never have enough of. You're going to find women who kick-ass and save, and actualize their destinies, while having flaws and being human. Also, the story doesn't do what you expect it to do. And while respecting genre tropes, it challenges old narratives within its genre, as well as within West African society and culture, about a woman's place, etc. It directly challenges and interrogates them, and by so doing charts a new course of visual possibilities. That is to say, there are other ways we can tell our stories. We don't always have to conform to one thing, or one story about us, or one way of making films. We can do anything.

This project also comes at what I think is an opportune moment, as the film industry almost globally has been forced to confront its history of not only gender disparity, but also sexism and misogyny (see the #MeToo movement especially). And even more so with regards to the representation of women of color—specifically black women in this case, as we see demand for varied stories about black women seemingly surge to satiate a hungry, growing audience. So as you take on this story that's inspired by a very popular African folklore, which squarely centers black women, and in ways that we rarely get to see them represented on screen, are you in any way influenced by the zeitgeist?

I've been developing and writing "Mami Wata" since early 2016, pre the #MeToo movement. It just so happens that the themes and philosophy of the story resonate well with the movement, and I'm all for it. Listen, If you go to most African communities, you're going to find women running things. Yeah, sure the men may have all the fancy titles and such, but you'll find that the women really decide how things go within their families and in the larger society, and they do most of the heavy lifting too. This is what I grew up knowing via my mum and my late sisters. I've never been able to see women as second-class citizens, until I became an adult and realized that it was a thing—this global perception of women as somehow inferior to men. Now, I may not be able to champion every single cause, but I sure as hell can make movies with strong, black women kicking ass.

I've come across a few short films inspired by the Mami Wata legend; the one I recall most is fellow Nigerian filmmaker Bolaji Kekere-Ekun's Nkiru, which you've probably seen. But I was actually surprised to find a number of feature films as well, although none of them are familiar to me, including Beninese filmmaker Mustapha Diop's Mamy Wata (1989), which I found very little information on, and doesn't seem to be easily accessed. Although it appears that it traveled internationally (screening at film festivals across Europe for example), which can sometimes be an indication of how strong a film is. Did you perform any research on past films inspired by the folklore, and if so, can you share anything that you discovered, or what you might have learned that maybe influenced your approach to your own film.

I did a lot of research, and I learnt about Diop's Mamy Wata, but I haven't seen it. I also realized that a few filmmakers have tackled, or tried to tackle the subject. Why not? It is an intriguing mythology. I actually think artists don't tackle it nearly enough. And certainly not enough in cinema. But there's also a lot of superstition surrounding the lore. I didn't find many cinematic works about Mami Wata, and those few that exist certainly are not accessible. So with my approach, I realized early on that I would have to treat it as a thriller, and really ground the narrative in reality. But really, most of the stuff I know about Mami Wata comes from oral tradition. Which, as you know, oral tradition is a huge part of what shapes African belief systems, especially in West Africa. But with those very ideas I found very strong gems for me to tackle the even bigger ideas about African femininity, our spirituality and identity.

Your crowdfunding campaign lists a goal of $120,000. Is that the final budget for the film, or do you anticipate having to seek additional funds, and this is just an initial phase?

That's the entire budget for production and post-production, which is really small if you think about the cost of making feature films around the world. We plan to work with a small crew, but the very best, and mostly non-actors, except for the leads, with principal photography set for an intensive four weeks in this gorgeous and untouched fishing village between the Lagos and Benin republic border, right next to the Atlantic Ocean. And the great thing about making a film is that you can do it in stages. So if we can get through principal photography and have our rushes in the can, then that in itself will open up other possibilities for post-production and collaborations. I'm not in a hurry to make the film, if it means compromising on the quality. It's much too important.

*

Indeed.

After a world premiere at the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen in Germany earlier this year, Obasi's latest work, the aforementioned short film based on Nnedi Okorafor's Hello, Moto, is currently touring the international film festival circuit, drawing praise from fans and critics alike. It's scheduled to make its UK premiere at the Southbank Centre in London on July 20, as part of its annual Africa Utopia program which celebrates arts and culture from the continent. The film will then head west to the Fantasia International Film Festival in Montreal (one of the world's most significant genre film festival) which kicks off on July 22.

Tambay Obenson is a Brooklyn-based writer and filmmaker. Obenson also is the founder and former operator of Shadow and Act. You can follow him on Twitter at @TambayObenson.