Reclaiming Tradition: How Hair Beads Connect Us to Our History

A history of beads and African hair jewelry told through the unforgettable story of Baroness Floella Benjamin.

In 1977, Trinidadian-British actress and singer Floella Benjamin (OBE) was on her way to premiere her new blaxploitation film Good Joy at the Cannes Film Festival in the south of France. Styled in braids carefully accented by layered beads, she knew she'd standout amongst the festival's mostly white attendees, but nothing prepared her for the kind of reception she would ultimately receive.

"We drove along the [Promenade of] La Croisette," she recalls, "in an open top Cadillac for the film premiere and as we passed along, the crowds tried to grab my hair to get a bead as a souvenir."

It was a decade when sequined jumpsuits, gaudy fur stoles and overgrown sideburns were the norm, yet Benjamin's beaded look—which many black folks would have considered common—was met with unparalleled fascination—a uniquely African hairstyle that black women had been wearing for centuries hadn't been seen before at a place like Cannes. "I stayed at the Carlton Hotel and the maids were intrigued," she recalls. "They kept knocking on my door just to look and stare at me."

The 70s were also a time of radical black power movements, when dashikis, afros and braids became emblems of black pride and beauty. Benjamin's decision to wear beads at an international event was an extension of that. While she hadn't expected such a fanatic response to her hair, she was, acutely aware of the power and cultural value of the style from an early age. "When I was twelve my father sent me a postcard from Liberia of a woman wearing beads in her hair and I really wanted to look like that when I grew up. So I had been wearing plaits and beads as a hairstyle for years and it was nothing unusual for me to wear my natural look for the Cannes Film Festival," says the actress.

The reclamation of African aesthetics by black women through the ways in which we wear our hair is occurring once again. Many black women are using hair jewelry like beads, gold cuffs, and multicolored string to accentuate natural or protective styles such as braids, locs and twists. This "trend" however is rooted in the black hair experience. Whether or not we realize it, for many of us, our relationship with uniquely black hair accessories started at an early age.

I remember, quite vividly, sitting between my mother's legs as she parted my hair into impressively symmetrical sections, applying copious amounts of grease as she fashioned my strands into a neat, age appropriate style. If she happened to be in the mood that day, she'd add a few plastic clips in the shape of bows or sunflowers or a set of clear "bubbles," often against my wishes—I just wanted to be done doing my hair already.

These were looks and stylistic accents that I only saw on other black girls—signaling to me at an early age that our hair and the way we wore it was distinctive.

As I grew older, I opted for hair styles that I thought were more "mature," whether that be bum-length box or micro braids, synthetic ponytails or weaves, or my personal favorite: "Dominican Blowouts." These were worn sans the hair accessories I grew up sporting. The wearing of such accessories both in childhood and now is intrinsically connected to longstanding African traditions of status and beautification.

The wearing of hair jewelry is a beauty practice that long predates our present-day interpretations. "Just about everything about a person's identity could be learned by looking at their hair," Lori Tharps, co-writer of the book Hair Story told BBC Africa about early African braiding practices.

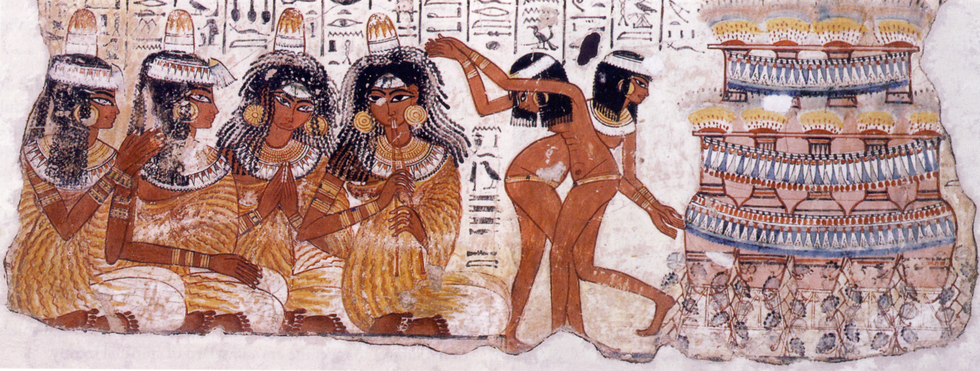

These styles weren't just about aesthetics and functionality. They were also markers of social standing. In Ancient Egypt people commonly wore alabaster, white glazed pottery or jasper rings in wigs, depending on which materials were available locally, they were symbols of status and authority, with those of high class ranking, let's say a young Cleopatra, using them to signify wealth and status.

Hair adornment played a similar role in early West African civilizations. In many communities braid patterns were used to identify marital status, social standing and even age. In present-day Cameroon and Côte d'Ivoire hair embellishments were used to denote tribal lineage. In Nigeria coral beads are worn as crowns in traditional wedding ceremonies in various tribes. These crowns are referred to as okuru amongst Edo people, and erulu in Igbo culture. In Yoruba culture, an Oba's Crown, made of multicolored glass beads, is worn by leaders of the highest authority.

Hair ornaments have been worn by Fulani women across the Sahel region for centuries, who adorn intricate braid patterns with silver or bronze discs, often passed down from generations.

Early uses of hair jewelry were also seen in East Africa. Habesha women from the northern regions of Ethiopia and Eritrea drape cornrow hairdos with delicate gold chains that usually fall past the forehead when in traditional garb. Members of the Hamar tribe in the Southern Omo Valley are known to wear their hair in cropped micro-dreadlocks dyed with red ochre and use flat discs and cowrie shells to accentuate styles.

Some of the earliest beads to be used as adornment were found in 2004 at the Blombos Cave site near Cape Town. They were made from shells and date back 76,000 years.

In a more contemporary sense, hair jewelry has become less of a status symbol and more a stylistic one. Rather than being used as a signifier of one's tribe or social standing, braids, twists and locs worn with adornments have come to represent stylistic individualism and—more symbolically—a pushback against the prevalence of white beauty standards. The wearing of hair jewelry took on a different function in modern history through members of the diaspora who were conscious of what it meant to wear styles associated with their African heritage.

The 70s brought about a renewal in the embracing of African aesthetics by African descendants living in America and the UK in particular. This increased exposure, championed by people like Benjamin, inspired a fury of global fascination in line with the era's knack for eclecticism. When the actress began appearing on the BBC children's show Playschool, the obsession only grew. Children and adults alike regularly wrote to Benjamin, asking her for tips on how to achieve her beaded look. They'd show up to appearances rocking their own versions of her signature do—"Floella look alikes," as she calls them.

Benjamin witnessed, firsthand, an unprecedented shift towards the embracing of African-inspired fashion as her career progressed—a departure from the rigid respectability models that governed expressions of black fashion in previous decades. "In 1973, when I went for a modeling photo shoot, I was told by the editor, that their African magazine was for sophisticated women, and that only tribal women wore their hair in plaits and beads. So for me to be acceptable I had to put on a curly wig," says Benjamin. "Thankfully about six years after I had proudly started wearing my beads, African plaits and beaded hairstyles became fashionable. Women all over the world, including America, suddenly didn't feel embarrassed or ashamed to look like an African woman."

"Playboy even asked me to pose for their centerfold in nothing but blue beads," adds Benjamin.

Some historians, however, credit the American actress Bo Derek, who wore stocky beaded cornrows in the 1979 film 10, for introducing the style to US audiences—effectually undermining its African DNA and transforming it, in part, from a black cultural export to a pop culture fad. While black women had been wearing the style for centuries, a single white women received substantial recognition for its appeal—an increasingly common occurrence carried out, today, by white celebrities like the Kardashians, whose "boxer' and "Bo Derek" braids" have been praised as novel trends despite being obvious rip-offs of black hairstyles.

Nonetheless, the roots of such aesthetics can't be easily obscured. The wearing of beads and hair ornaments on braids, remain an unmistakably African tradition, upheld by black women—and men in many instances—across continents.

Many popular black figures in the latter half of the 20th century embraced the style as well. Miriam Makeba, one of the earliest African women musicians to gain crossover success, boldly wore beads during international performances in the Xhosa tradition. Artists from the diaspora embraced these looks too. Figures like Rick James, Stevie Wonderand the jazz pianist and singer Patrice Rushen, became widely associated with wearing intricate braid patterns with beads in American popular music during the1980s.

Who can forget how Venus and Serena Williams famously brought their clanking, multi-colored beads to tennis courts in the early stages of their careers—displaying blackness on an international platform where black people had often been forced to abide by strict notions of "proper" decorum. Despite having rather unimpressive athletic abilities myself, I remember relating to the Williams sister simply because of how they presented themselves to the world. In my mind, they were the only tennis players that mattered. Alicia Keys' Fulani-inspired braids, which she often accented with beads upon entering the musical spotlight in the early 2000s, were another example.

Now, the hair jewelry trend has resurfaced in new ways—due, in part, to the shift towards natural styles that began to occur within the black community nearly a decade ago. Styles like twists and braids lend themselves more innately to African-inspired hair jewelry. According to celebrity hairstylist Susy Oludele, who's worked with the likes of Beyoncé, Solange and Zoë Kravitz, requests for items such as dreadlock cuffs, beads and metallic string have increased significantly amongst clients of her Brooklyn-based hair salon Hair By Susy.

"The demand is really high, everyone wants accessories, because we're getting back to our culture, back to our identity," says Oludele. "It brings out more of the style, every bead, every clip means something—back in the day cowrie shells were used as currency. Cool right?"

Social media has helped increase the trend's visibility and the widespread availability of vintage images online, allow for style-conscious black women to create new interpretations while drawing on the past for inspiration. It's something that Oludele herself is known to do with her innovative, colorful designs that exude youthful energy and often make generous use of accessories. For her, these styles are all about channeling bold energy, individualism and "coolness." The artist Solange has cited Patrice Rushen's iconic mane as the inspiration for her heavily beaded looks, as seen in the video for "Don't Touch My Hair."

Today, hair jewelry has become more readily available in black salons and hair stores. Women across the diaspora wear hair ornaments with contemporary interpretations of African hair designs regularly. They're a go-to for natural hair artists and style influencers, who consider them a simple yet expressive way to add bold color and luster to looks.

While early trendsetters like Ms. Benjamin had to navigate untoward reactions to black hairstyles from white observers, there's an increased "everydayness" to such hairdos in today's style landscape—though issues of cultural ownership and the policing of black women's stylistic choices still exist. For many it prompts a few fundamental questions: why do trends that black women have worn—and have been scrutinized for wearing—for actual centuries only warrant mainstream attention when co-opted by the Kardashians? And how do we make it stop?

The dominance of Eurocentric beauty standards mean that reflections on African histories and cultures of beauty are increasingly important, as they allow us to understand the full depth of our contributions to global beauty phenomenons. They also remind us how utterly substantial our cultural influence is.

The current popularity of natural black hairstyles and decorative accessories comes from a legacy of black women proclaiming "blackness" and "Africanness" for the world to see—but not to touch (or steal as a keepsake).

Benjamin has gone on to earn both an OBE and a BAFTA Special Lifetime Achievement Award for her contributions to television, and now acts as the chancellor of University of Exeter, advocating for young people at policy level. While her success extends far past her acting days, she still adds one special cultural achievement to her resume: "Beaded hairstyles became a global cultural fashion statement that is still visible today and I am thrilled to have helped established that identity movement," she declares proudly.

- The Hidden World Of Harlem's African Braiders - OkayAfrica ›

- Natural Beauties Share Why CURLFEST 2018 Is More Than Just a ... ›

- Our Favorite Natural Hair Gurus Share Tips on How to Keep Curls ... ›

- 9 Black-Owned Goodies for the Natural Hair Lovers in Your Life ... ›

- This Black Hairstyle Collective Is Embracing the Beauty of Natural ... ›

- Zozibini Tunzi Slams Racist Hair Advert - OkayAfrica ›

- Photos: Danielle Mbonu's New Hair Braiding Series - OkayAfrica ›

- Photos: Danielle Mbonu's New Hair Braiding Series - OkayAfrica ›

- Here are the African Women on 2020 BBC '100 Women' List - OkayAfrica ›

- Zulaikha Patel Celebrates Black Hair With New Book 'My Coily Crowny Hair' - OkayAfrica ›

- Moving to Ghana Reinvigorated Jewelry Designer Aisha Asamany - OkayAfrica ›

- Moving to Ghana Reinvigorated Jewelry Designer Aisha Asamany - OkayAfrica ›

- How Fashion Historian Teleica Kirkland Is Transforming What We Know About Clothing From the African Diaspora - Okayplayer ›

- Photos: This Is What the Melanin Unscripted x Native House Pop-Up Looked Like - Okayplayer ›

- Photos: The Best Street Style Outfits From Lagos Fashion Week, 2019 - Okayplayer ›

- South Africa's New Miss SA Has Renewed Conversation Around the Politics of Black Hair - OkayAfrica ›

- Introducing OkayAfrica's 100 Women 2019 List - OkayAfrica ›

- A Rastafarian Girl Was Banned from School in Kenya Because of Her Locks - Okayplayer ›

- 'The Hair Appointment' Is a Gorgeous Photo Series Showing the Beauty of Black Hairstyling - Okayplayer ›

- 100 Women: Susy Oludele and Alsarah On the Power of Following Your Passion - Okayplayer ›

- Black Girls Only: A Playlist of Our Favorite Black Girl Anthems - Okayplayer ›

- These Striking Photos Bring the Phrase ‘Black Girl Magic’ to Life - Okayplayer ›

- 100 Women Letter From the Editor - Okayplayer ›

- What It’s Like To…Run an African Hair Salon in New York City - Okayplayer ›

- How Can Zimbabwe Strengthen Its Already Sliding New Currency? - Okayplayer ›

- Curly Hair Salons in Cairo are Paving the Way for a Nascent Natural Hair Revolution | OkayAfrica ›