With ‘Voices,’ Ghana’s Art Scene Tells Its Own Story

A new book collaboration aims to introduce the world to the vibrancy of the West African country’s visual arts community.

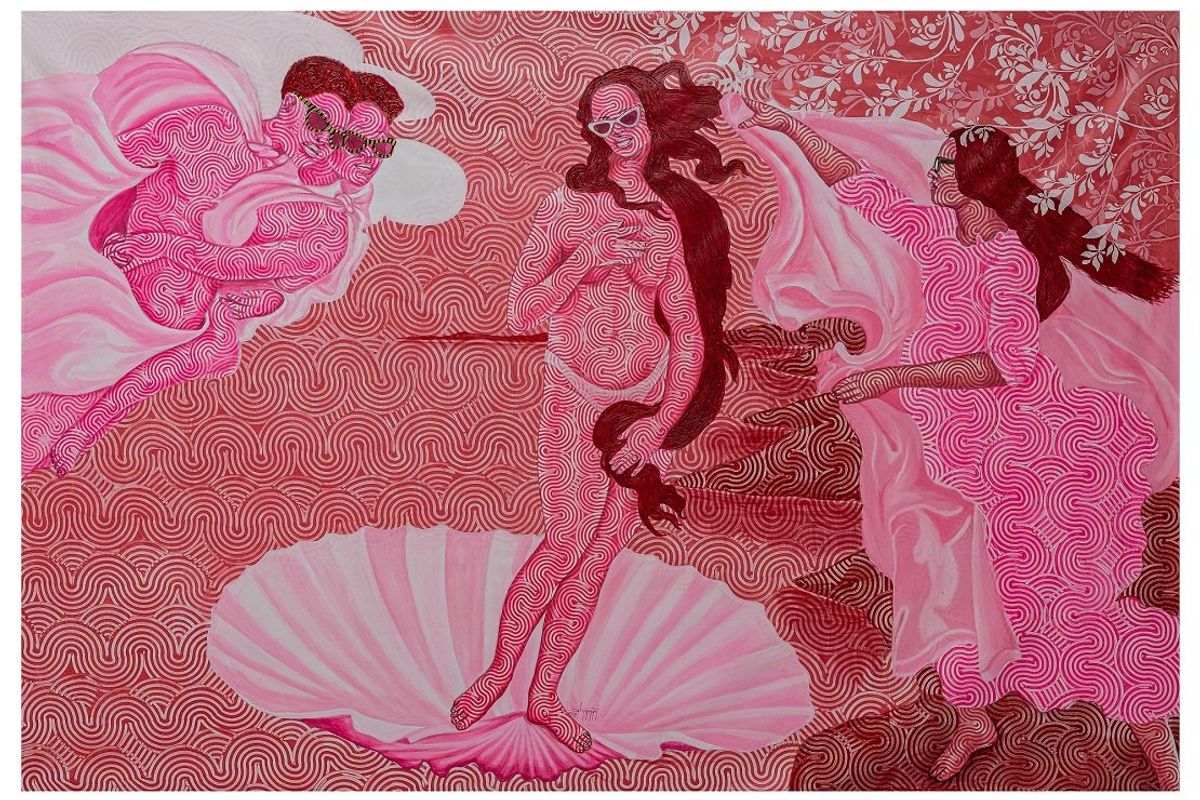

Akosua Venus, 2022.

The opportunity to communicate one's thoughts and ideas is often appreciated by people in the creative arts, even if they usually prefer their work to do all the talking. In the forthcoming book VOICES: Ghana’s Artists In Their Own Words, visual artists from the West African country chronicle their art journey and practice – as the title suggests – in their own words.

Writer and curator Ekow Eshun’s foreword sets the stage for what is billed as a first-of-its-kind, a book that sees the artists, and in addition, curators and gallerists, talk about their work and Ghana’s art scene in first person. It features interviews with over 80 people, including Eshun, James Barnor, Chrissa Amuah, Foster Sakyiamah, Rita Mawuena Benissan, Osei Bonsu, Larry Ossei-Mensah, and Campbell Addy.

The book is a collaborative project between Accra-based pan-African digital platform and creative studio, Manju Journal, and London-based independent publishers Twentyfour ThirtySix. It showcases a broad range of artists, from those working in the digital realm to illustrators, sculptors, fabric designers, and ceramicists. “We wanted to bring the theme of community to this book, so that’s one of the main things we looked at when selecting these artists,” says Richmond Orlando Mensah, founder and artistic director of Manju Journal.

OkayAfrica spoke with Mensah in the run-up to the release of VOICES: Ghana’s Artists In Their Own Words in September.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

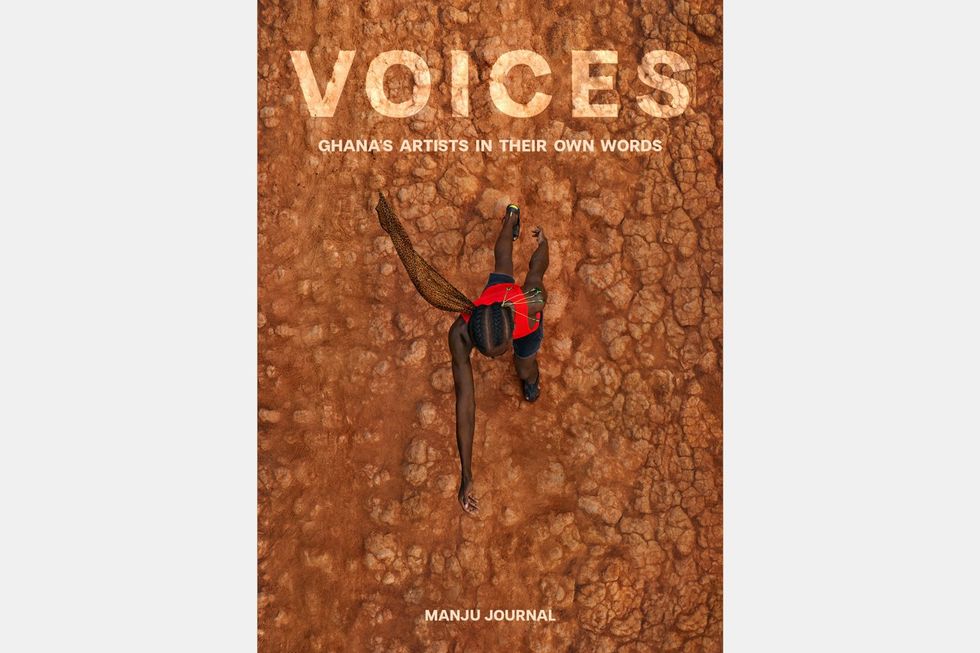

What’s the story behind the cover of the book?

The cover is an original one we shot. It was a collaboration between myself and my colleague, Kusi Kubi, the fashion director for Manju Journal. With VOICES, we have a broad range of artists, from 94-year-old James Barnor and Ablade Glover [who’s in his late 80s], to newly graduated art students. The inspiration for the cover is that we want this book to serve as a guide for the next generation. That's where we had the model on the cover; you could see that his hands were stretched, one moving forward and one way moving backward. It’s like passing something from the next generation on to another. We didn't want it to be a literal way of passing something on to someone, so we had to create it artistically to complement the book.

How did you decide on who to include in the book?

The initial idea for VOICES was to talk about the general Ghanaian creative scene. We [thought] it was essential to focus on visual art, a broad topic. Rather than limiting ourselves to paintings, which we always see, this book is an educational piece for anyone interested in exploring contemporary art. We wanted to also showcase to the world that there is more to art than painting as a community or creative platform.

We’ve had talks with other artists like textile designers or ceramists who sometimes come into the country and say, ‘Okay I am from the diaspora, I have been trying to find my way to exhibit some pieces in Ghana, but the institutions or galleries [are] looking for just painters or artists. There is no institution here giving us chances – those who are into sculptures and ceramics.’ These are some of the things we had to sit down and then try to analyze and show the world that there is more to art. Even with institutions as well, it’s somehow limited here.

Even with photography, when you come to Ghana, it’s pretty challenging to have institutions dedicated to photo exhibitions here in Accra or Ghana. The idea was also to let people know that art is vast. Ghanaians grew up with art as part of our culture and heritage, but we want to explore what art is.

The book features different generations of Ghanaian artists, from James Barnor, who is 94 years old to Courage Hunke, who is 23 and maybe the youngest. Was the idea to trace the history from decades ago, and not limit the book to contemporary Ghanaian artists?

When we met most artists like Serge [Attukwei Clottey], they were referencing the [older generation of] artists like Ablade Glover. We have the foreword, the introduction, and the afterword with the book's themes. The afterword is written by Paul Ninson, who discusses the importance of archiving today, tomorrow, and the future.

As much as we are talking about the contemporary art scene, we must respect those who paved the way for some artists we are now celebrating. Most of the artists were even giving a lot of credit to these names. There were so many names that it was essential to champion them as part of this book.

The idea was that most of the artists were referencing these names, and as much as this book serves as an educational piece, it was essential to showcase the broad range, not just limit ourselves to some of these current names. But also, newly graduated art students taking art as a full-time job [are] featured in this book.

Were you looking for something specific in the artists who were included?

There was no unique selection. There is familiarity with some of the artists we've worked with, those we got introduced to, and those we researched. One challenge about this book is that if we reach out to the artist and they are unavailable, there is no way we could have the artist featured in the book because we want the artists to talk about what they do as artists, what inspires their work, what they think about the Ghanaian creative art community.

We reached out to many artists, and those who were available were those we had to focus more on. What I also want to clarify is that the VOICES book is not a definitive guide to what is happening in Ghana. We don't want this book to be [seen as] ‘this is the [top] hundred percent artists we think are doing best.’ No, we want this book to introduce what is happening in Ghana.

Were you surprised by anything in researching the book's Institutions and Resources section?

As much as this book is also an educational piece for anyone interested in exploring Ghanaian contemporary art, we also wanted to highlight some institutions in Ghana that, in recent years, have supported these artists making waves in the country or abroad. We even had to go to Dubai to feature the work of Efie Gallery, which shows Ghanaian art in a different part of the world.

I realized from this book that there was a sense of community. Instead of being the opposite way of competition, it was togetherness. The galleries mentioned each other, so there was this connection of ‘it’s not just my institution or as a founder but also about other institutions supporting Ghanaian artists.’ That was something unique I realized when interviewing the founders of these institutions in Ghana.

- The Biggest Photo Library In Africa Just Opened Up In Ghana ›

- A Ghanaian Artist Brought A Boat To This Year's Art Basel Miami ›

- Spotlight: Ghana’s Sarfo Emmanuel Annor Is Celebrating African Beauty ›

- Jambo Spaces is Bringing Change to Ghana’s Creative Scene - Okayplayer ›

- Ghanaian Artist Alfred Addo Uses Sawdust to Capture the Beauty of Everyday Life | OkayAfrica ›