From Lagos: Monday Is For Beans

Part two in a series of autobiographical essays about food, Nigeria and blackness by Tunde Wey.

This is the second in a series of autobiographical essays from chef Tunde Wey who, as we recently announced, will be taking his From Lagos dinners on a U.S. tour in order to explore ideas and issues around Blackness in America.

African men don’t cook but my father—full bearded, with powerful arms at either side of a taut potbelly—was emancipated from this stereotype, if only partially.

He only cooked on Sundays.

Any other day, he didn’t step into the kitchen unless he was trying to reach our frail second floor balcony. He was a powerful man and the insecure railings squawked in muffled anxiety as he leaned against them while imperiously giving orders to the scurrying workers or kids below.

Sundays started early in my house. Back then my father was the most devout of Catholics, attending mass seven days a week—Sunday being the culmination of his piety. For my father, mass might have been welcome, but for us kids it was insufferably long.

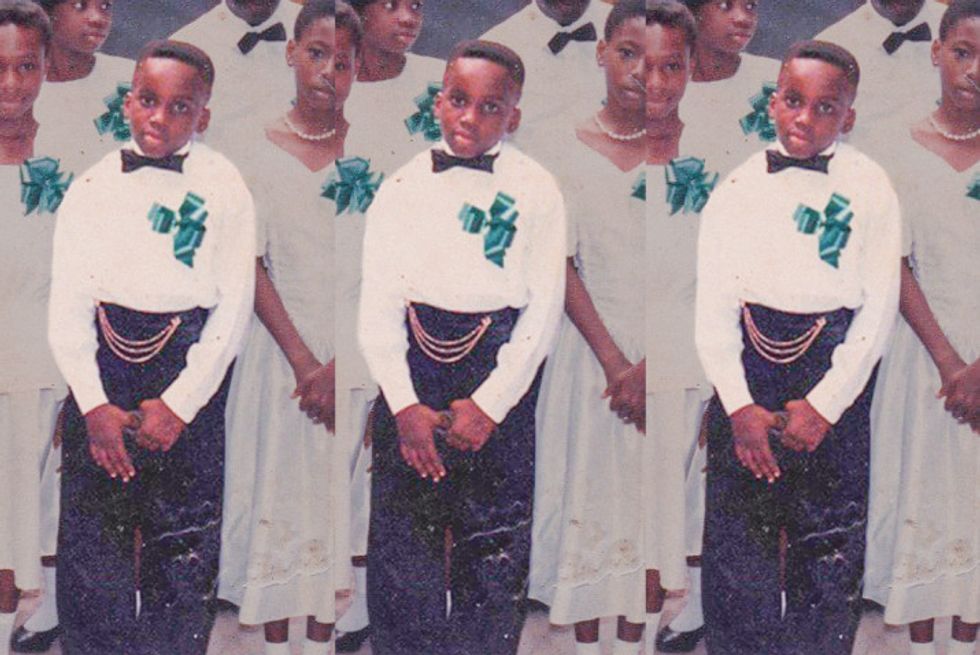

At the beckoning of the reverend father, an interminable ritual of would begin: stand, kneel, sit, stand, sit, kneel, keep kneeling. Keep kneeling. Never mind the kneel rest wasn't cushioned. My nine year old body was so preoccupied with the hard wood pinching my knees through my smart Sunday pants that I routinely fumbled my Hail Marys.

Often, physically tired from these liturgical calisthenics, my siblings and I slumped deep into the hard wooden seats looking for comfort where none resided. My father would shoot us the stoniest of church glares and it was enough to stiffen the most noodly spine. Sometimes he was softer, and one lucky kid was allowed to fall asleep between my parents, swaddled between my mother’s plump shoulder and my father’s starched, and lightly-cologned side.

Every service, my mother would stuff money into our hands for the church offering, and as sure as god’s fiery sun shined, we would part the sum in two with the lesser for Catholic trio of Jesus, Mary and God, and the greater loot stored away for sin.

Sneaking out of the church, under the guise of a bathroom visit, we escaped into the bustling street outside the cathedral's compound where we furtively bought iced yogurt.

"Stolen water is refreshing. Food eaten in secret tastes the best!”

This was the most delicious yogurt ever, worthy of a scalding from eternal flames.

It was packaged in a pyramidical box that was impossibly convenient for my accursed eight year old grip. It fit in my hands so nicely, I convinced myself that god had made my hands exactly for this moment. The vendor seemed to know my crime but always had a smile for me as she cut a pyramid tip with a razor, creating a sheared teat from which to suck the perfectly-tart yogurt ice.

I had very little time to enjoy the treat, fearing my protracted absence would raise suspicion. Inevitably I would disembowel the package, break the large ice chunk into smaller pieces, stuff them in my mouth, crushing them to tinier, tangier snow flakes as I hurried back into the church. My mouth reflexively puckering from the tartness as i shuffled back to my parents.

My father always eyed me suspiciously when I returned but he never said a word.

*******

After Sunday Mass, my father turned to the kitchen to begin an altogether different kind of service. Sundays were special for me because it was the only day we didn’t eat traditional Nigerian food at my home.

My father’s Sunday meals were legendary and elaborate affairs, taking three, sometimes four hours to prepare.

By the time he was done, it was well into the afternoon and my inner starving African child sat at the foot of the kitchen, eyes vacant, belly distended, overzealous flies buzzing around me. Years later, after moving to America, I realized my father was just a fan of Sunday brunch.

In the kitchen, my father was mounted by a newer more ebullient spirit. His Sunday somberness was replaced with whistles and singing. This brawny man was now a nimble prancer: light on his feet, pivoting between the stove top and the prep countertop, pirouetting and plieing, as he cracked eggs, shook caramelized bits free from a saucepan’s bottom and sliced and diced the entire world.

When the table was eventually set for six—two parents, four children—there were twenty platters, each one pressed down, shaken together and rolling over.

Sautéed meats and vegetables; mounds of sandwiches and deeply colored salad; eggs in styles conventional and inspired; beans—baked, boiled and brown; fatty bacon and thin turkey slices; sausages uncloaked from their cases—naked, plump and glistening.

Then there were things I had never seen and probably would never see again. My father was an inventor, taking ordinary foods, dislocating them from their previous references and manipulating them into new and different shapes, flavors and textures.

When brunch was over, everyone was so full nobody moved until Monday.

*******

I was a spoiled little bastard and once I made up my mind about something I was “as stubborn as a goat”—my mother’s words.

Which brings us to the time, at nine years old, when I got fed up with traditional food and—much to my parents bemusement—I petitioned for Sunday meals everyday. After a lifetime of traditional food I felt it was time for a new direction in the family.

My decree:

All traditional foodstuffs in our home are henceforth classified as contraband!A cessation of all pungent indigenous aromas and flavors!

No more chopped onions and pureed tomatoes for stew!

All permutations of indigenous fish: smoked fish, stock fish, dry fish, crayfish, are to be banned!

Garri (dry cassava) is to be discarded!.

The entire house is to be forever free from the smell of frying palm oil!

No more chopped okra and discarded water leave stems stacked in a pile of chlorophyllic disappointment!

Brown yams, smelling the way they taste, bland and nutritious and slimy—no more!

I presented these demands to my parents. They ignored me.

“You want oyinbo food eh? Mtscheeww.”

Instructions were given to our house help to only serve me plain white rice, fried plantains and plain tomato stew. It was a compromise I accepted triumphantly, until i got jealous of my siblings. My lips didn’t have the patina of oil and satisfaction theirs did after meals. I pretended to be content with my “less-african” chops while I watched them devour flavorful and fragrant soups.

Afang: a leafy hot stew of binary flavored greens, festooned with shelled periwinkles, roe stuffed crabs.

Ogbono: deeply flavored— all the way down to the bottom of your soul—and mucilaginous, presenting as nothing but umami to the taste buds.

Owo: a rare delicacy, unavailable but for the few times when it had to be fetched from distant relatives visiting from even more distant places. Yellow, thicker than it was thin in its savory consistency. A thoughtful dish lathered over myriad varieties of steamed freshwater fish, marine snails.

*******

Things fell apart the day my father returned home one evening with a black nylon bag. His strong arm reached into the flimsy bag to retrieve two items.

The first was a steaming perfectly rounded mound of amala, wrapped in clear cling wrap that was sweating from heat. It was brownish-black, glossy and smoother than a skipping pebble—about the size of my groaning belly.

Next was soup in a bowl, similarly covered in cling wrap. It was a startling yellowish orange color, creamy and smooth in consistency. Chunks of assorted meats lay provocatively in it. Around this main soup were, a deep red pepper stew pressing it one side and a jute green sauce flanking the other. A delicious red chili oil formed a perimeter around the trio of viscous vittles.

Black, red, green, yellow; a technicolored dream clawed at my eyes. The intoxicating scent led by the rising steam burrowed into my nostrils. All that glorious meat made my prepubescent legs tremble slightly, as my stomach lurched in excitement. I stared at my dad, blinking and quiet. He looked at me and we both knew my strike was over.

“Gbegiri, is what it’s called. They make it from beans” he said after we were done eating. My lips slightly smarting from the dish’s heat, a sting i had missed. With both our pants unbuckled, we sat reclined on the couch. I was full. It was Monday.

*******

Amala with gbegiri, ewedu and stew was served during the first two dinners of the Blackness in America series. Those beans are a bitch to peel though.

ABOUT THE SERIES

My name is Akintunde Asuquo Osaigbuovo Ojo Wey. I was born in Nigeria to Moses Akinlaja Wey and Oghogho Beatrice Wey (nee Okundaye). I am the third born, wedged between Thelma, Tope and Seyi. At 16 I moved to Detroit, Michigan. I’m a cook + writer, launching a new dinner series exploring BLACKNESS IN AMERICA. Each dinner will gather an intimate group of diners to converse around this theme. We explore this theme by sharing personal stories, and discussing how our lives and work intersects with blackness.

I am accompanying these dinners with autobiographical essays and stories which reflect my own black experience. This is the second installment.