I Went To The First Well-Read Black Girl Festival and Remembered I Was Born to Write—And Read

A personal essay from OkayAfrica contributor Alisha Acquaye on the impact the first WRBG Festival had on her as a writer.

It took several years for me to call myself a writer, and two decades to actually believe it. I once wrote that sometimes black women have a harder time claiming this identity (that of a writer) because we aren't exposed to many black women writers in school. We know the classics, womanly wordsmiths who weave sentences into tapestries depicting a vivid fabric of the black female experience. Maya Angelou. Toni Morrison. Alice Walker. But I wasn't taught about these women in public school. No, I was force-fed the realities and imaginations of white male authors, and although I found some notable, most felt superficial, politely racist and bland. But most importantly, they made me feel lonely. I wanted to write, but there weren't many black women to show me the way. To make me feel at home.

Although claiming the title as writer was a journey, identifying as a reader required no thought or restraint. I was that girl who went to the library during my lunch breaks. I saved up my coins for book fairs, that magical time of year when the gym or auditorium transformed into a playground of chapter books, pencils, glitter pens, silly-shaped erasers, bedtime book lights and bookmarks. As an adult, I still love a good book store: the sweet, nutty scent of weathered literature or the fresh laundry aroma of unopened books, tall shelves closing in like hallways heavy with the weight of words, the way book covers are like the faces of friends we haven't made yet.

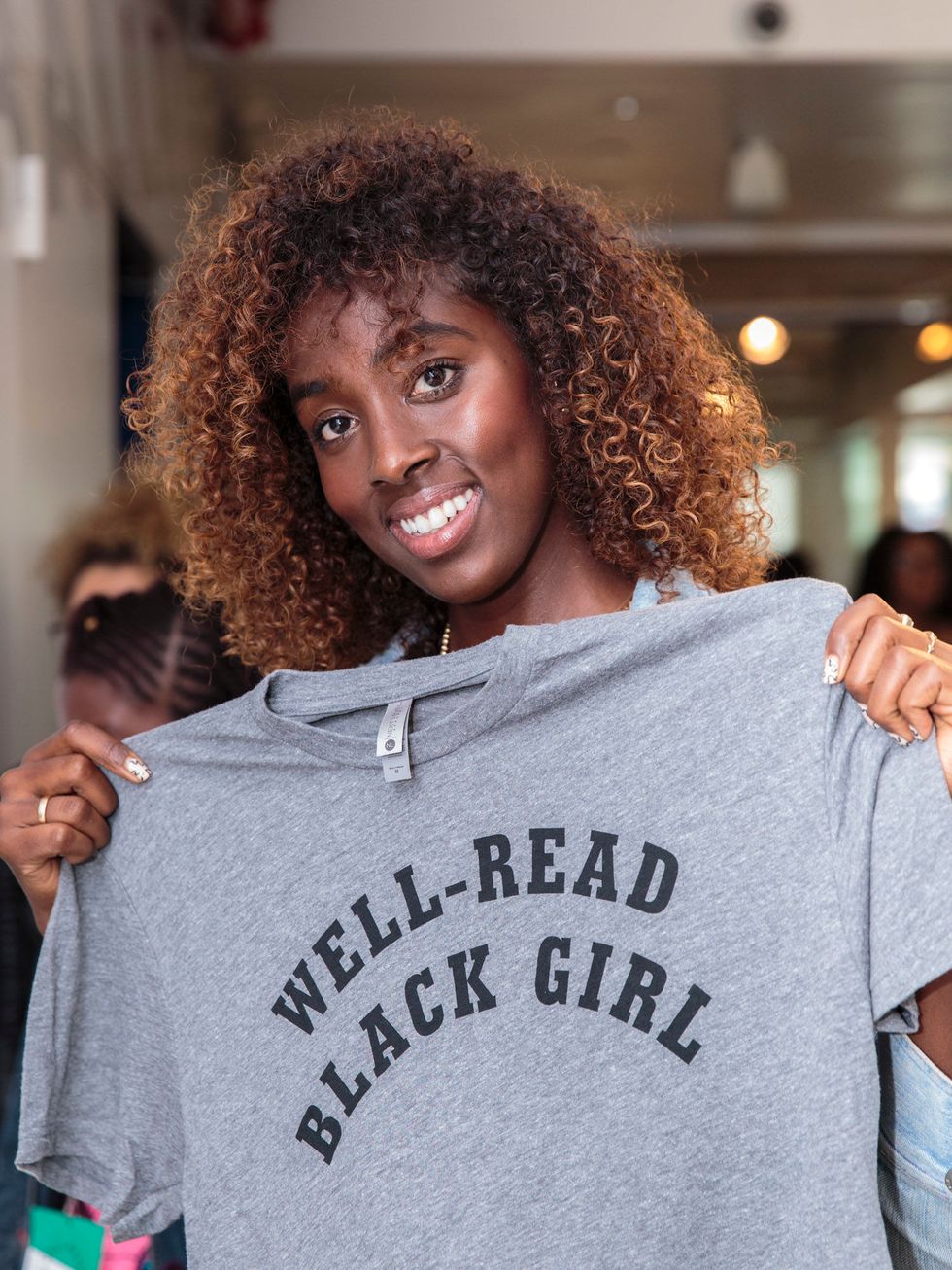

No doubt, there is a joy about book fairs, book stores and especially book clubs, where small communities of people can dive head and heart first into a book, together. I knew all of this while walking into the very first Well Read Black Girl Festival last Saturday. For the past few years, more prominently than before, black women have been building spaces that celebrate our natural hair, our complexions and our self care methods, but WRBG celebrates our love of literature, and the black women who continue to write our truths. WRBG is revolutionary: it invites black women who identify as both readers and writers to geek out over a new book, to feel empowered through storytelling, and to recognize our magic and influence in the literary world.

The bubbly and friendly Glory Edim floated through the festival like a book fairy. In wide framed glasses, a curly tapered fro and a lacey pink maxi dress cloaked by a classic denim jacket, she seemed exactly in her element. Edim has been organizing the Well Read Black Girl book club since 2015, and I've had the pleasure of attending and moderating some of her monthly meetups. In only two short years, she and her team managed to not only leave an impression on the hearts of the women who attend her club, but an imprint in social media and the web, where the WRBG Instagram and Twitter have over 50,000 followers combined. The Kickstarter campaign for the WRBG conference and festival garnered close to $40,000—three times their goal of $15,000. It shows that black women have the power to make any dream possible, and that, when something that is missing is finally found, we listen, we support and we help it flourish into something grand.

Edim teared up during her opening remarks, expressing that this festival, this community, has helped her find her purpose and her people. Like Edim, I found myself tearing up at several moments throughout the event, especially during Naomi Jackson's stunning speech on inclusion, writing with the women in her family in mind and finding her ground as a writer. At one point, I looked around the auditorium, taking in the many shades of brown, the many textures of tresses, and the collective expression of peace and comfort on everyone's face. It was where I needed to be.

The festival was composed of panel discussions led by some of the rising and seasoned stars of literature and online writing. Jacqueline Woodson, Jenna Wortham, Morgan Jerkins and Ashley C. Ford were just a few names on the impressive roster. I ferociously took notes during their discussions, as if tattooing their advice and mantras onto my brain. The self care panel was, itself, a healthy dose of medicine: Ford said she “doesn't enjoy writing, but having written," revealed that she keeps an away message in her email to have more control over her inbox and to reply to messages in a healthier fashion; Jerkins said that “black suffering is profitable" and realizes that online outlets often seek black writers to express their anger and pain about the state of America, but that we need more stories on black joy and happiness; and when Bassey Ikpi said that writing that she doesn't like makes her write better, I realized that, yes! Writing that I deem trash is just as instrumental for me as writing that I love.

Writing is such a solitary, singular path. The act itself begs us to sit still, to be silent, to somehow extract our thoughts from brain to fingers to pen or laptop. It is a process we must execute alone. Reading asks us to exercise this similar discipline of oneness and patience. When we finally share our writing, or converse about the book we adore, we have to undo all of that loneliness and be vulnerable with another, without knowing if they will approve our writing or worse, hate the same book that undid the knots in our soul. It fascinates me that writing and reading require such solo movements, while the act of sharing it is public, unpredictable and nerve wracking.

And yet, the energy at the WRBG fest was open, willing, excited: whether the emotions were similar or the opinions different. Writing doesn't have to be lonely, nor reading: it can be another place for us to build connections, to slowly lessen the insecurity or discomfort of sharing our deepest selves and most personal projects. After all, we are all storytellers—we have all the tools to share a great story within us, we just need to get it out there—remnants of the Fireside Chat between Rebecca Carroll and Tayari Jones that I will remind myself whenever I am stuck on a sentence, hesitate to send a story to a friend, or feeling trapped between the creases of a book.

We were meant to be there, to surrender to the graceful intensity of words, to remember that stories are within us: whether we write them down or reminisce on the persistence of a memory. Reader or writer, black woman, black daughter, black aunt—we carry generations of narratives within us. We are the most magical storytellers, were there to witness the first sentences the world scribbled like cracks in the earth. We write the past, the present and the future into one never ending novel.

At the vendor table, while I held an arm full of books to my chest, unsure of which to purchase, I started asking some women for advice—“Did you read this one?" “What did you think?" and I greedily offered my opinions as well, when I saw someone's hand gloss over a novel or their eyes linger on a book cover with that familiar expression of hesitance and curiosity. It was like my elementary school book clubs all over again, but this time more mature and just as colorful.

- These 7 African Women Poets Will Keep You Calm, Cool, and ... ›

- For Black Women, Self-Care Can be a Radical Act - OkayAfrica ›

- Glory Okon Edim — OKAYAFRICA's 100 WOMEN ›

- Glory Edim ›

- In Conversation: Glory Edim on Her Debut 'Well-Read Black Girl ... ›

- Photo Essay: Two Congolese Women Rebuild Their Lives In Detroit ... ›

- 13 of Our Favorite Books On Black Resistance and Revolution - OkayAfrica ›

- BBC Snubs 2019 Booker Prize Winner Bernardine Evaristo - OkayAfrica ›

- These Stunning Naturals Give Us Their Best Hair Tips From CURLFEST 2017 - Okayplayer ›

- OkayAfrica’s Most Anticipated Events of 2025 | OkayAfrica ›

- Ten African Women Musicians to Watch | OkayAfrica ›