The Incredible Stories Behind Lemi Ghariokwu's Iconic Fela Kuti Album Covers

Nigerian artist Lemi Ghariokwu reveals the incredible stories behind his highly-political Fela Kuti album covers.

Today marks the 20th anniversary of the passing of Fela Kuti. In remembrance, we're revisiting this article with his trusted collaborator Lemi Ghariokwu, who created the large majority of Fela's album covers.

Nigerian artist, illustrator and graphic designer Lemi Ghariokwuis the creative force behind 26 of Fela Kuti's album covers. His highly-political artwork paired illustration and collage with acute social realism, becoming a crucial visual accompaniment to Fela's anti-establishment records.

Lemi's covers are instilled with social commentary and, like the afrobeat legend's songs, they directly call out government corruption, political oppression, police brutality, skin bleaching and much more. We called up Lemi at his home in Lagos to get the story behind seven of his iconic Fela album covers.

In following pages, Lemi describes the vision, work, and occasional fights behind the covers for Fela's Alagbon Close, Everything Scatter, Fear Not For Man, Sorrow Tears And Blood, Yellow Fever, JJD and Beasts Of No Nation in his own words.

Read Lemi's incredible Fela stories ahead.

Enter code 'YEAHYEAH' and get 20 percent off of the FELA collection at the Okayafrica Shop until April 15.

Alagbon Close (1974)

Alagbon Close laid the foundation for what I was going to do for Fela through the years. I didn't illustrate his lyrics literally in my cover artwork, but showed my own take on what Fela was trying to express. My art was a supplement to the music.

It was a bit spiritual. I'd just met Fela a couple of months before this cover—my first Fela cover, by the way. Before I met him I'd done my version of the album Music Of Fela Roforofo Fight. When the opportunity, came to do Alagbon Close I cut out the image of Fela I had on my original Roforofo and ended up pasting it to complete that Alagbon cover. It's like a little collage, but there's no evidence (laughs).

Roforofo Fight was about a fight in the mud, so I illustrated Fela dancing on a swamp. For Alagbon Close, when I was doing the imagery, I thought that image of Fela dancing on mud would also work as him dancing on the police.

For me, the album cover expresses the victory of good (Fela) over evil (the police). The whale capsizes the police boat, so nature helps Fela defeat them. On the left, Fela's house Kalakatu Republic is standing on solid rock and the police jailhouse is on fire on the right.

When Fela saw the cover, the first thing he said was, “Wow, God damnit!"

—Lemi

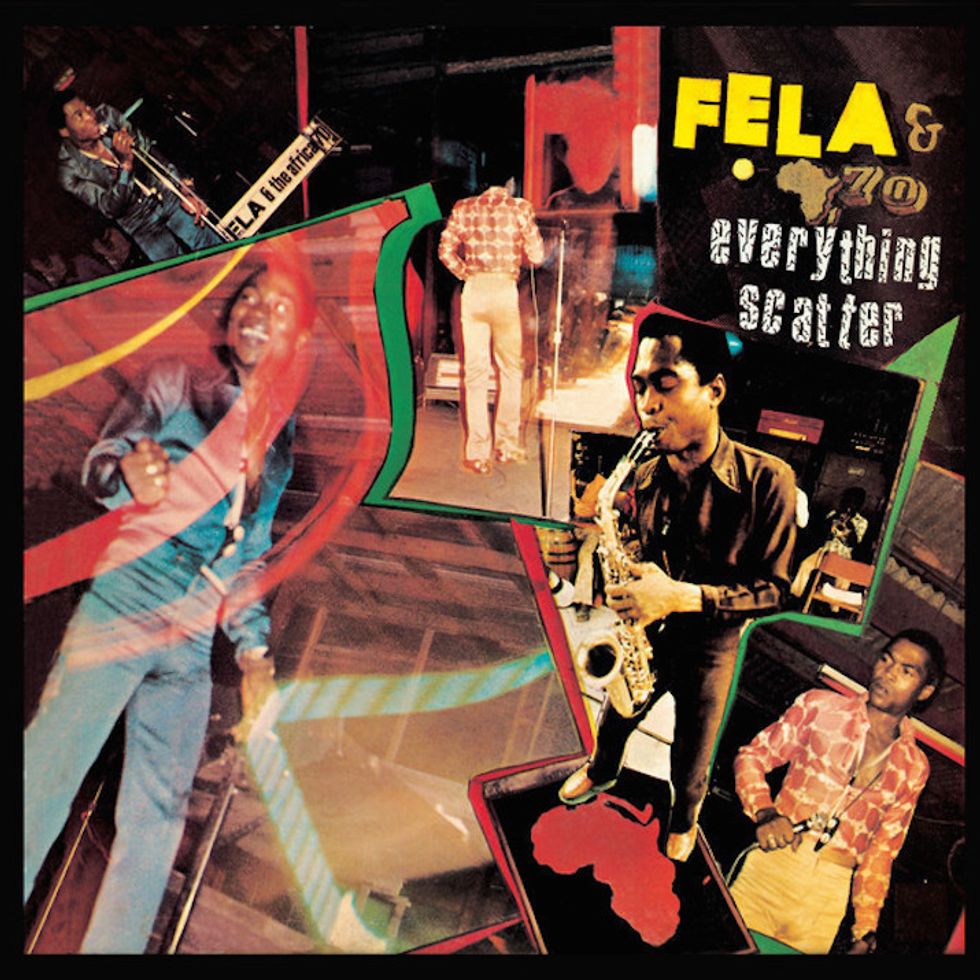

Everything Scatter (1975)

Because I'm self-taught, my style is eclectic. Fela allowed me to express myself the way I wanted. Sometimes I'd go to an exhibition, see a style I liked, and try it on the next cover.

For this one, I decided to do a photo collage. I included pictures of Fela's brilliant children on the back sleeve because I was deeply involved with his youth movement Young African Pioneers. We interacted with the audience, and people wondered if he had children, so we felt it was an opportunity to put it on the back album cover. It also includes pan-African heroes Fela mentions on the record's B-Side like Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah.

For the front, I was interested in the branding I'd seen from reggae music—on album covers by The Wailers, Bob Marley, Island Records, and so on—so I read up on everything and used this cover to brand Fela.

—Lemi

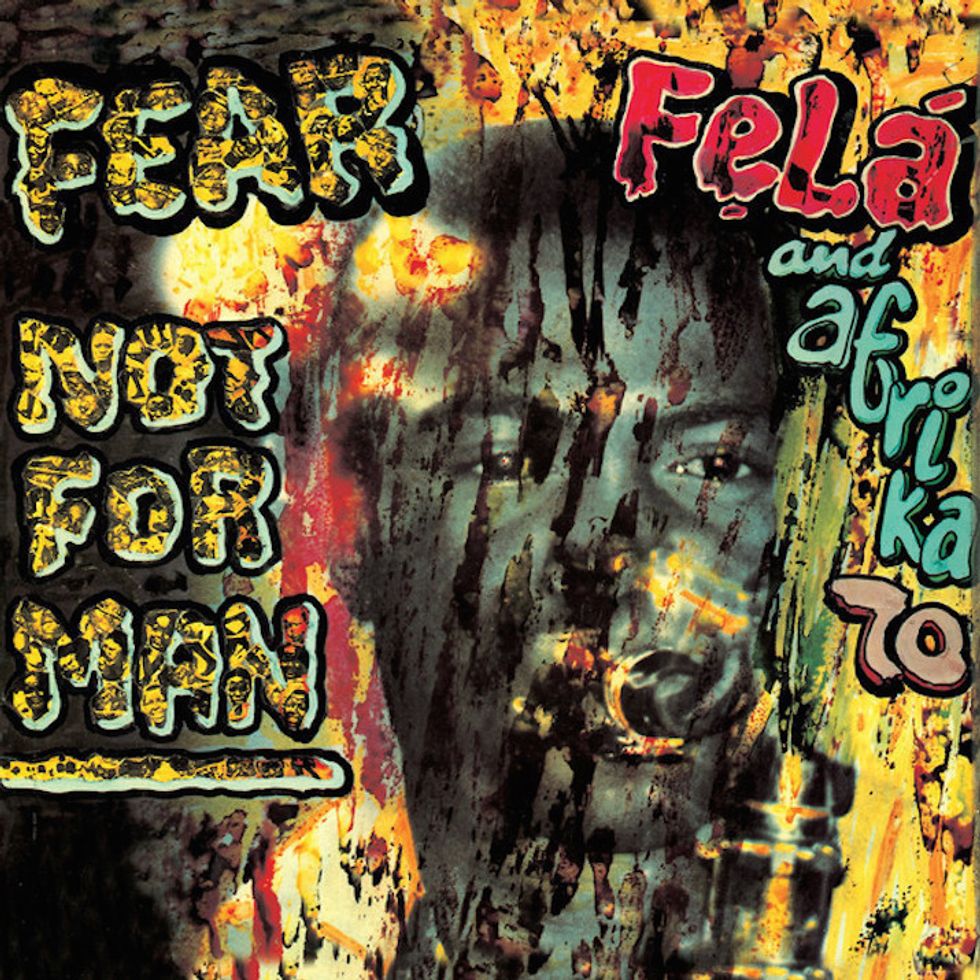

Fear Not For Man (1977)

At that point in time, Fela's sound was burning. I was scared. A lot of people were scared for Fela's life. Fear Not For Man is very short, very blunt, it expresses fearlessness through few lyrics.

I used a photograph by Tunde Kuboye, I loved its black-and-white effect which made Fela look bold and defiant while blowing the saxophone. I then painted over it with ecoline, which gives it that blood effect. Since Fela was advocating for people to be fearless, I cut out images of many Nigerian faces for the lettering of the title.

On the back cover, I made a comment so people could see my point of view. I quoted Kwame Nkrumah saying “Practice without thought is blind; thought without practice is empty."

—Lemi

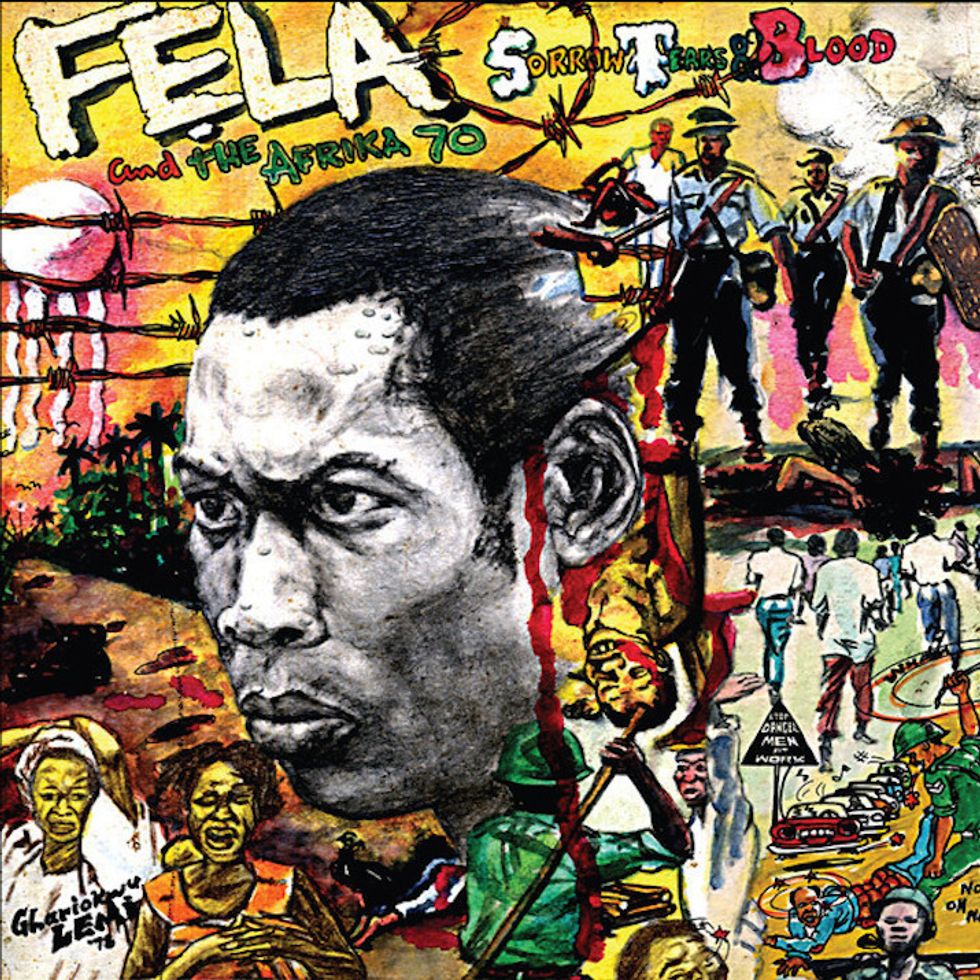

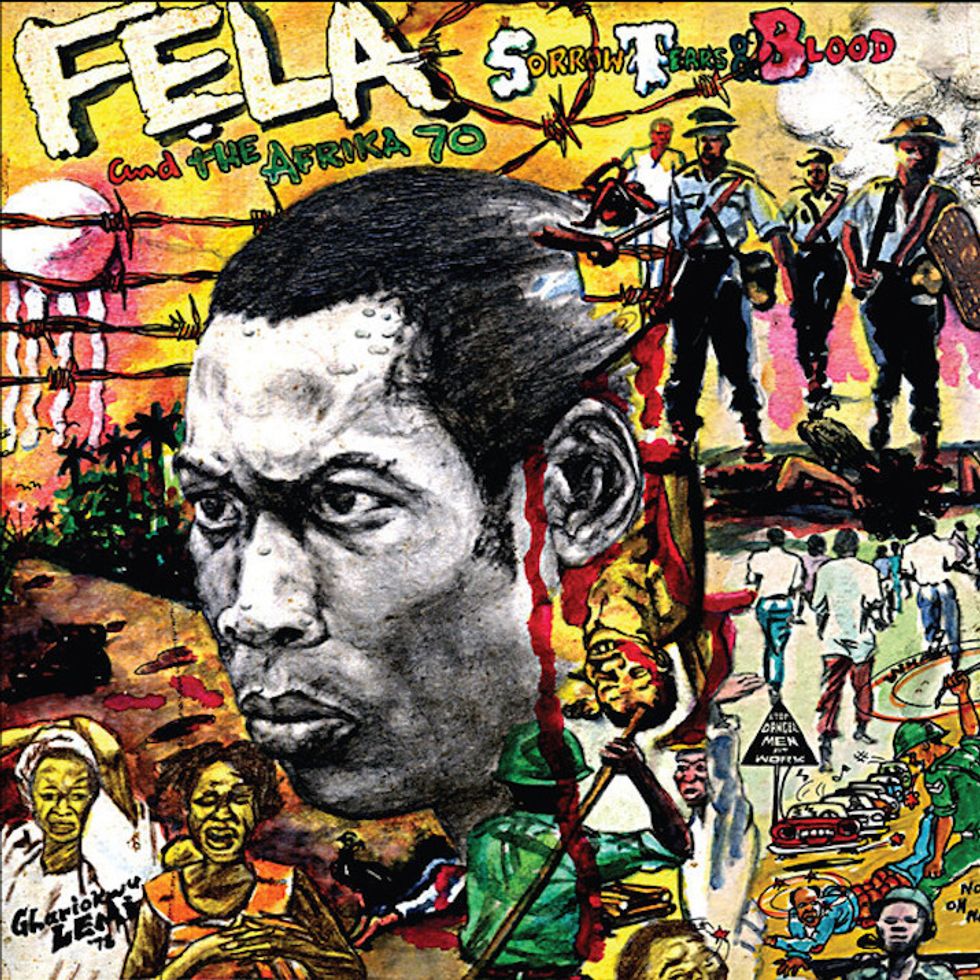

Sorrow Tears And Blood (1977)

I have goosebumps. This cover broke my relationship with Fela for 8 years. There were actually two covers: the first one was a black-and-white photo of Fela, which was the originally published cover.

I was 23 at the time and me and Fela had some personal issues. Our egos were clashing. When I presented Fela my art for Sorrow Tears and Blood he saw it as an opportunity to clip my wings. He thought I was getting too big for my shoes so he lampooned the piece (laughs). He remonstrated with me. I was heartbroken, started crying and left his place. I told my colleagues, "I'm not coming to Fela's house again." I was so hot and I had reason: I didn't need to be treated that way. So Fela had a colleague of mine do an impromptu cover (the black-and-white cover).

I held on to my cover for 25 years. In 2003 it was used on the book cover for Fela: From West Africa To West Broadway. So the artwork that Fela rejected in 1977, and I held on to because I was convinced of my work, ended up on the cover of a book. When that happened, I looked up in the sky and said, "Fela, where are you? Come see now."

I spoke with Knitting Factory Records' Brian Long and told him that I wanted it on the cover of the new reprint of Sorrow. So by 2010, 32 years later, my cover ended up back on the cover of the album. I had my victory (laughs).

The cover is very dear to me because I was with Fela the night that inspiration came for the song. That's why it was painful that Fela rejected it. That night of June 16, 1976 we were visiting Fela's first wife Remi Kuti, and his children Femi, Yeni and Sola. It was Femi's birthday. As we sat in the living room, the 9PM news came on that students in Soweto had been shot by police and were killed—this was during apartheid. They were forcing the African students to learn Afrikaans, some students refused and the police went and shot them. As the news came on we all said, "This is crazy." For the rest of that week we discussed it a lot and Fela composed "Sorrow."

—Lemi

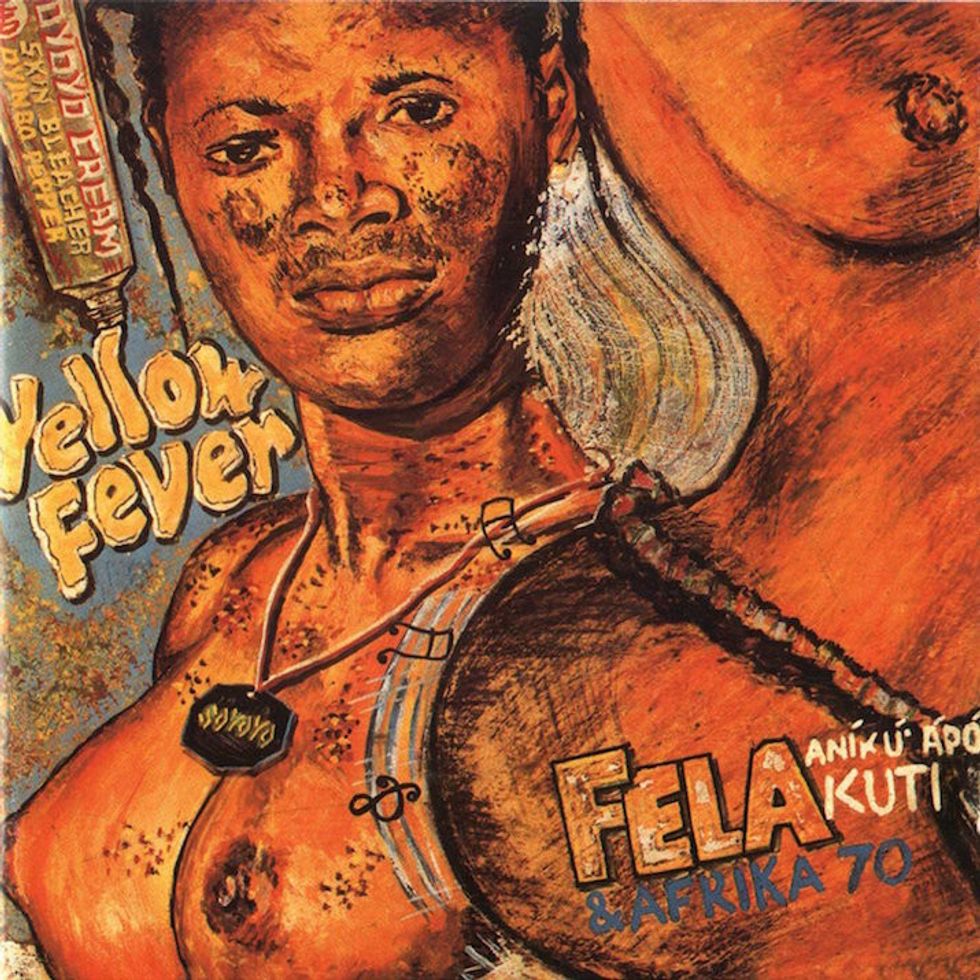

Yellow Fever (1977)

This title came from observations in the Kalakuta Republic. Fela was very observant and the 80 or so people that lived in Kalakuta would go out on the streets and come back with news, stories—juicy stuff. They'd also come up with different terminologies, Kalakuta slang for things.

African women were bleaching their skin and, from Fela and Kalakuta's perspective, when people bleach themselves they're a brilliant yellow color. It reminded them of the sickness called yellow fever, so Fela decided to write a tune to castigate women and tell them that bleaching is not good for them.

Being a pan-African, I always feel upset to see African women bleach skin and straighten their hair. So I saw an opportunity to express that vividly on the cover. I decided to do it minimalist and direct. I found a model in Kalakuta called KorKor. She modeled but she didn't bleach her skin so I had to add that in. I was hoping the other residents of Kalakuta wouldn't recognize her in the painting but when I showed it to them all the girls jumped; "that's KorKor!"

I put the price of the bleaching cream, called 'Soyoyo,' in the painting to show people how much they spent if they bought it. 40 Naira was quite a lot of money then. I also made the butt, upper lips and parts of the breasts of the model dark to show that there's no way the cream could cover it all. To me, there's nothing sensual about this cover.

—Lemi

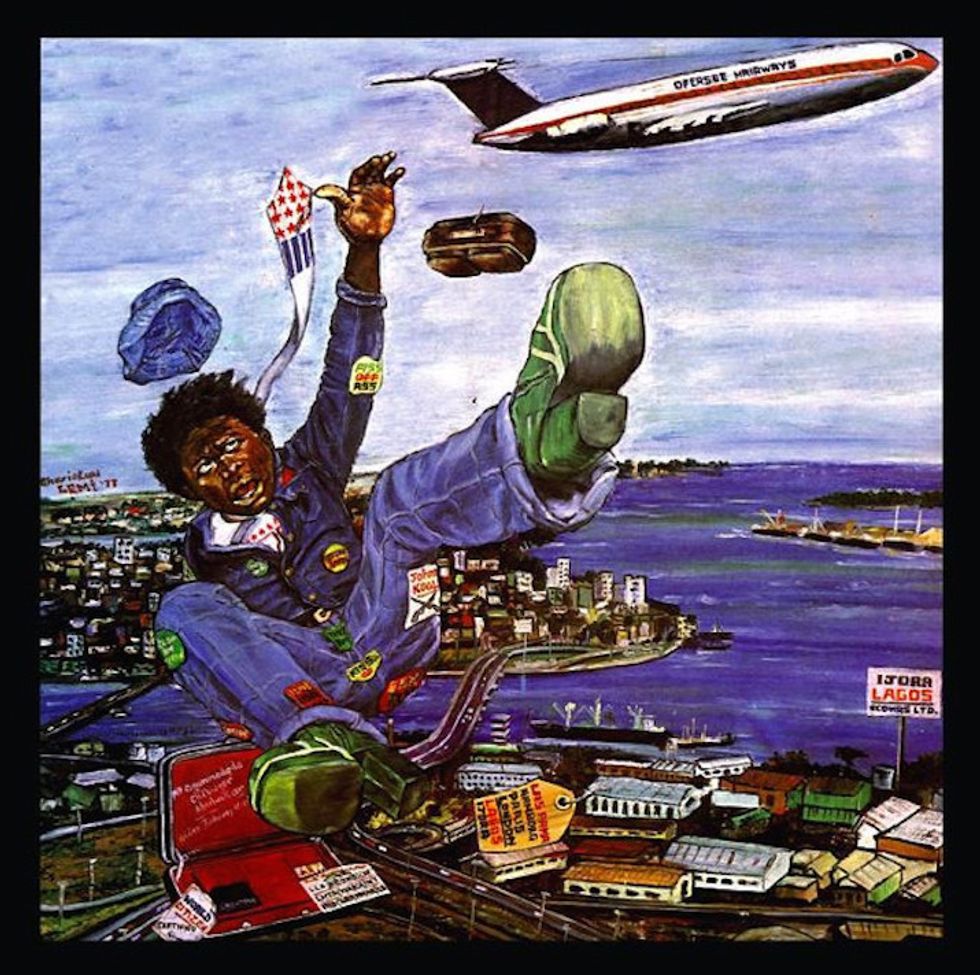

JJD (1977)

This was the first time Fela ever rejected my work (the second was for Sorrow Tears and Blood). Unlike Sorrow, I won the battle for JJD. The lyrics for JJD (Johnny Just Drop) disparages Africans who travel abroad and come back with Western mannerisms and dress in a Western style. It's Fela's take on JJC (Johnny Just Come), somebody who's fresh in town.

I strongly thought that I needed to address the youth with this cover, because the older folks, we can let them be. Some of them are near their graves already. For the back of the original cover I used a young man in denim jeans, a USA flag tie and 'I Love New York' and 'Jesus Saves' buttons dropping from an aircraft. It was an oil painting that took me 2 weeks.

I took it to Fela and to my surprise he asked me why I was attacking the youth with my art. Fela didn't want the youth to feel like they were being attacked. He preferred to attack the bourgeois. So he told me that I should do a bourgeois man that drops from the sky in a parachute and is the laughing stock of the people.

It was the only time ever that Fela gave me a concept for my covers and the first time he rejected my artwork—I was not pleased at all. So I agreed and made Fela's concept of the cover but when I finished I told the managing director of the record company, without Fela knowing, that it was going to be a double sleeve album.

When the cover came back the managing director sent for me to see the final product, then he told me go show it to Fela. I went to Fela's place and showed him the front cover and told him, "This is yours." Then I turned it around to the back and told him "This is mine." Fela's eyes went popping. He shouted “Lemi!" He said, "You hit below the belt man" and I ran out of the house.

I came back later and Fela looked at me from the corner of his eyes and just grinned, like he was thinking, “This boy... you're too smart."

—Lemi

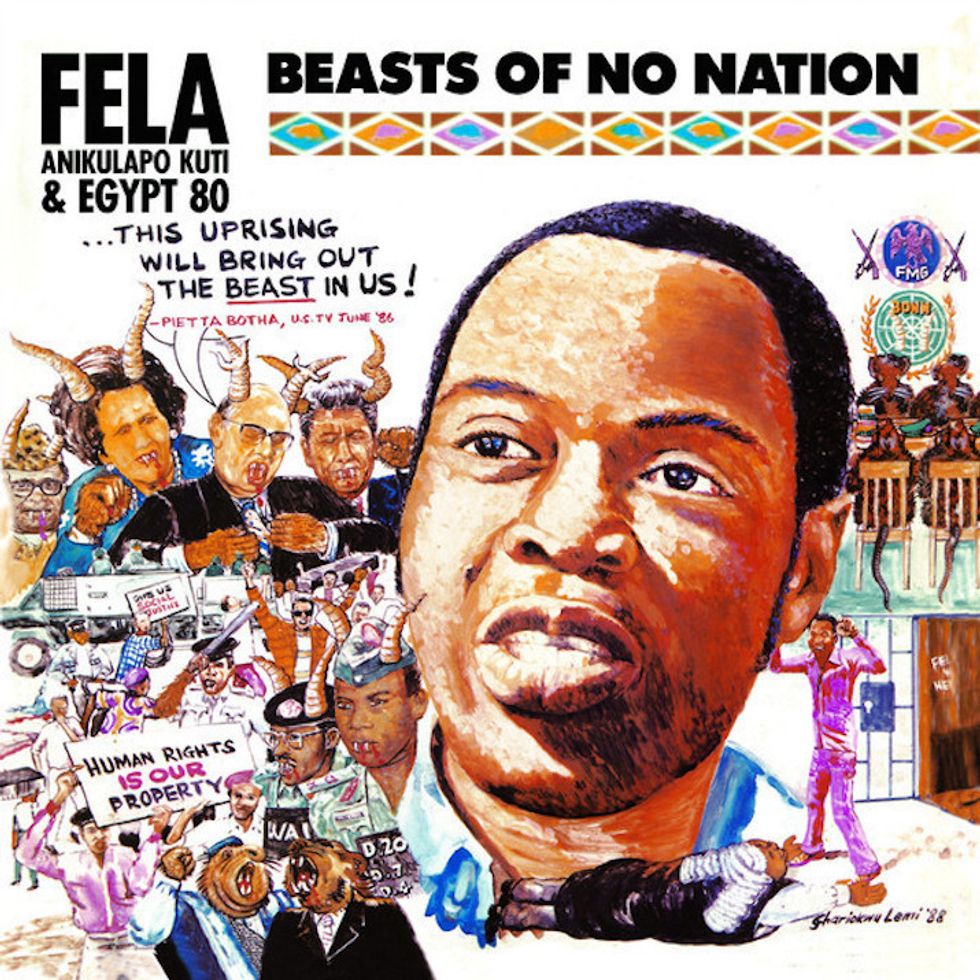

Beasts Of No Nation (1989)

That's the monster cover. Our current Nigerian president is on that cover.

I had broken away from Fela so I was on my own, but once in a while Fela's younger brother—who was handling his business when he went to jail—would send me a letter of invitation to have me listen to an album that could use a cover. One of those was Beasts Of No Nation.

I listened to the song and loved it, so I picked out the elements I needed to express several world leaders as bloodsucking beasts with fangs and horns. I was bold enough to put those leaders there. I even added Zaire's Mobutu Sese Seko who's not even in the lyrics. You should've seen Fela's face when he saw the artwork. He was grinning and saying “Lemi you crazy!"

General Buhari and Tunde Idiagbon are shown in the cover art but Margaret Thatcher, P.W. Botha and Reagan are the most prominent. Even when Thatcher died, the same day she died, I got two emails asking if I still had the same impression of her from this cover. I said "Yes, my impression hasn't changed."

—Lemi

- Fela Kuti – Okayplayer Shop ›

- Check Out Fela Kuti x Online Ceramics' New Merch Drop - OkayAfrica ›

- You Can Watch the 'Finding Fela!' Documentary For Free This Weekend - OkayAfrica ›

- You Can Vote to Get Fela Kuti On the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ›

- Fela's Nomination to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Should Have Come Decades Ago - OkayAfrica ›

- Fela Kuti, The Radical Fashion Icon - OkayAfrica ›

- Photographing Fela: Bernard Matussiere On His Iconic Images of Fela Kuti and the Kalakuta Queens - OkayAfrica ›

- New Fela Kuti Reissues & Box Set Are Coming This Year - OkayAfrica ›

- Audio Adaptation of Broadway Musical ‘FELA!’ to Debut on Clubhouse - OkayAfrica ›

- Where To Watch the Felabration 2021 Concerts This Weeks - OkayAfrica ›

- The New Fela Kuti Box Set is Curated by Femi Kuti & Chris Martin ›

- Fela Kuti Tribute Album Featuring D'Angelo, Questlove & More - OkayAfrica ›