Caine Prize Preview 2017: Who Will Greet You When You Get Home by Lesley Nneka Arimah

In this series we look at the Caine Prize for African Writing shortlist, going in depth to get at the heart of what makes these some of the best African short stories written in English last year.

Launched in 2000, the Caine Prize for African Writing is a award for short stories written by writers of African origin and published in the English language. This year’s 166 entries from 23 countries is the highest number of submissions in its 17 year history. The five shortlisted stories for the 2017 prize are:

- “Virus” by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene (South Africa)

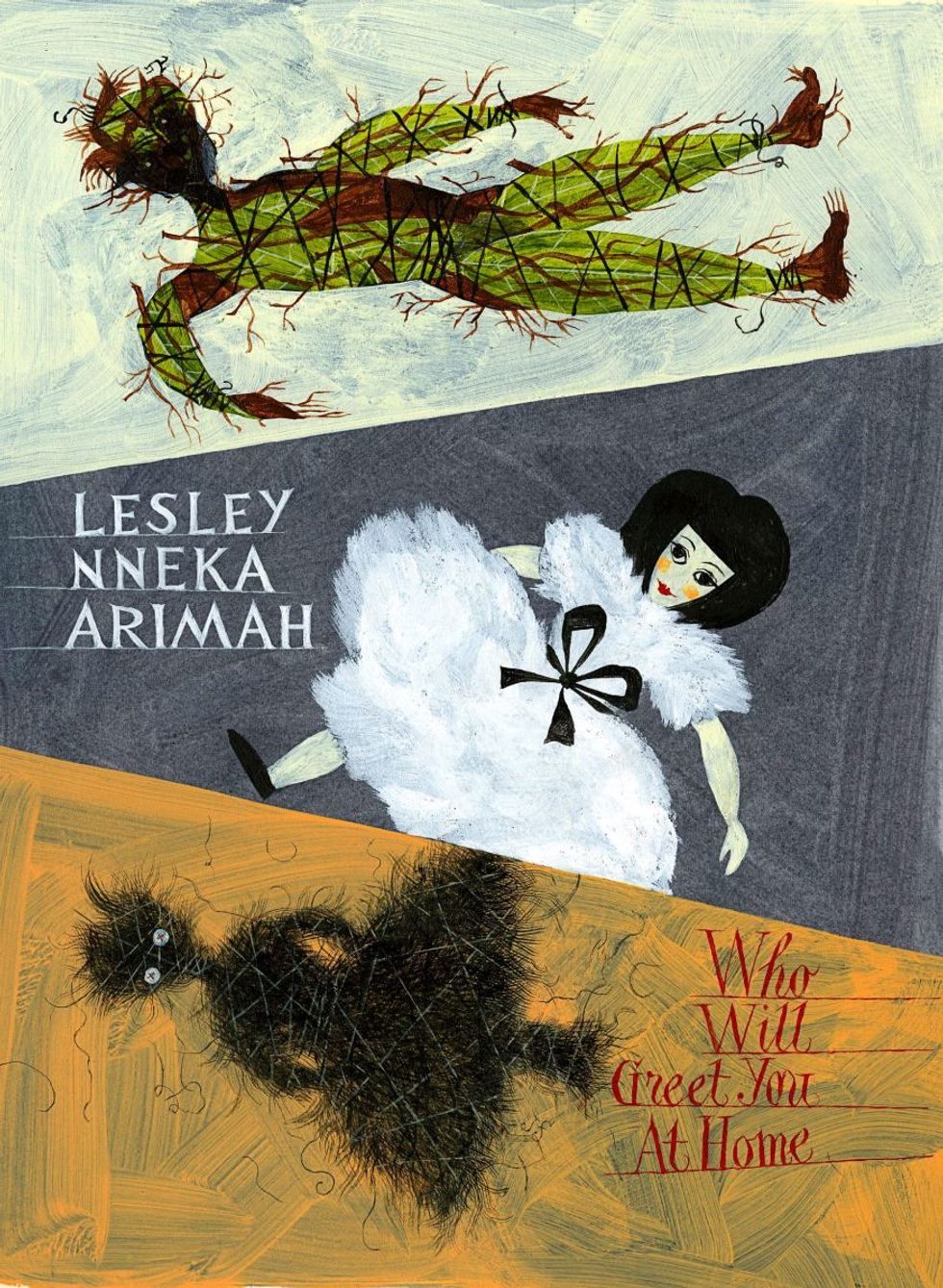

- “Who Will Greet You At Home” by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Nigeria)

- “The Story of the Girl Whose Bird Flew Away” Bushra al-Fadil (Sudan)

- “Bush Baby” by Chikodili Emelumadu (Nigeria)

- “God's Children Are Little Broken Things” by Arinze Ifeakandu (Nigeria)

This year’s winner will be awarded £10 000 and the other shortlisted writers will each receive £500 to be announced on July 3rd at the Senate House Library in London. OkayAfrica contributor Sabo Kpade will review each shortlisted entry leading up to the announcement of the winner on July 3rd. Entry one is Who Will Greet You When You Get Home by Lesley Nneka Arimah.

Hat tipped to the reader who grasps, on first reading, what Lesley Nneka Arimah is doing in her story Who Will Greet You At Home.

In the world which Arimah has conjured, babies are fashioned out of materials—porcelain, straws—which are then ‘blessed’ by a mother or ‘mother-figure’ turning them into beings with life different from the genetic makeup of humans.

Ogechi is the central character and a young woman who, due to a troubled relationship with her mother, has run away from home only to be shackled to her employer and a “mother-figure” addressed in the story as Mama, the dubious owner of the grandly titled “Mama Said Hair Emporium”.

Mama doesn’t only coerce and intimidate her staff for efficiency, she also coerces Ogechi into trading some of her “happiness”—a quality she appears to have in abundance but whose origins is unexplained—to shore up her already debilitating debt to her:

All that empathy and joy and who knows what else Mama took from her and the other desperate girls who visited her back room kept her blessing active long past when it should have faded. Ogechi tried to think of it as a fair trade, a little bit of her life for her child’s life. Anything but go back to her own mother and her practical demands.

What most impresses is how Arimah has grounded a most absurd idea in everyday reality so as to seem normal. She doesn't explain how this world came to be and it is this confident conjuring of otherworldliness convinces.

Absurdist tales are heightened realities that easily confuses some readers, yet Arimah compounds matters by incorporating other traditional elements of storytelling by way of folk tales about a young girls and hair, as well as call and response choruses.

She does so with an admirable economy of language all through. Ogechi is said to live “in an ‘apartment’ that amounted to a room she could clear in three large steps” and when working in Mama Said Emporium is said to keep “the store so clean a rumor started that the building was to be sold”.

There is the occasional flourish, “Ogechi weighed her options till sleep weighed her lids. Soon, too soon, it was morning”.

This forgives the inelegance of thrice repeating the word “haul” (“hauled” on one occasion”) - a pedant’s problem, no doubt but one which is made apparent by Arimah’s otherwise judicious use of words.

Take this sentence “She cradled the child, the scritch of its cries grating her ears…”. An unattentive writer would use the word “screech” to describe a child’s loud harsh cry, but if it grates then the precise word is of course “scritch”, a sound made from scratching.

“Who Will Greet You When You Get Home” was published by the New Yorker in late 2015. In an interview for the journal she said of her story that “there are many reasons why one would imagine a world without men, but, in this case, it wasn’t something I intentionally set out to do. Men simply never came up in my vision of this world. Perhaps there exists an alternate universe of men who insure their survival in equally fraught ways. Someone (else?) will have to write that”.

Arimah’s debut collection of stories “When A Man Falls From The Sky” was published in the US in April this year and is out in the UK this August. The book is a promised delight, going by the strength of her Caine Prize entry this year.

Sabo Kpade is a regular OkayAfrica contributor. His short story Chibok was shortlisted for the London Short Story Prize 2015. His first play, Have Mercy on Liverpool Street was longlisted for the Alfred Fagon Award. He lives in London. You can reach him at sabo.kpade@gmail.com