The Redemption of Burna Boy

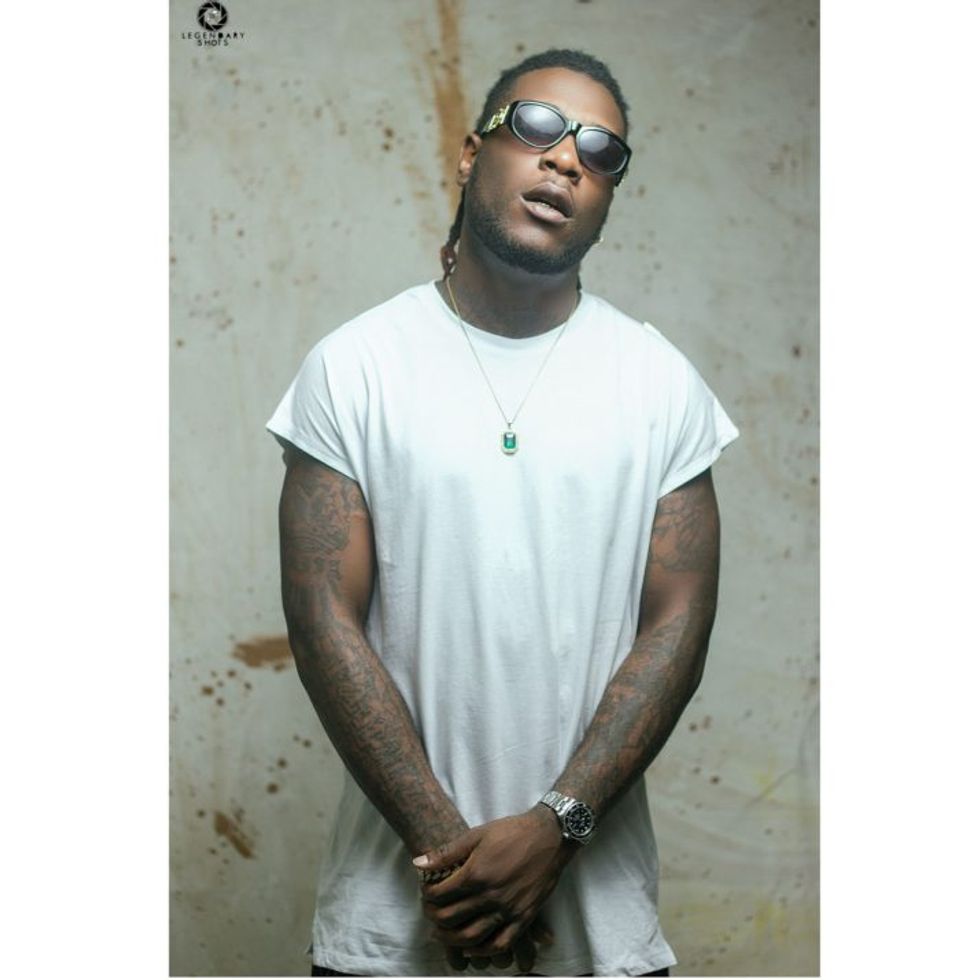

We Catch up with Burna Boy before his first UK show following a six year ban to discuss the star's controversies and his rich musical talents.

The Friday before Burna Boy’s October first “homecoming” concert at the Eventim Apollo in London, I check in on the twenty five years old’s social media pages.

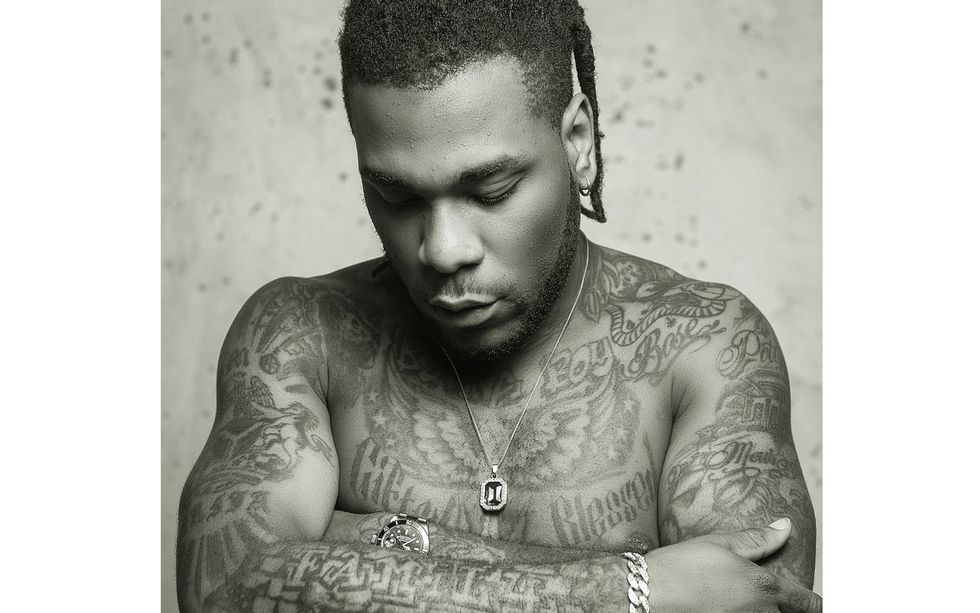

What were earlier square blocks of different photos is now one large wall of a brown-skinned figure, eyes closed, head tilted up with a hand on his face in what would look like a state of despondency if it wasn't for the thick smoke hovering over his mouth.

The photo captures the spirit of his new seven-track EP, Redemption, as well as that of the artist Burna Boy has become—a man whose primary musical instincts are now centre stage in a cohesive project that has a confounding array of influences—oxymoron surely but one that sells short the dizzying complexity that maps out the EP.

This is Burna Boy’s first full release since his 2015 album On A Spaceship. Since then there has been a slew of singles released, both original songs ("Acting Bad") and covers (Rihanna’s "Work"), each one showcasing a maturity that is as steeped in tradition as they are different from each other. Redemption is much shorter at seven songs, and more unified in its sound direction than his previous albums.

Our interview is scheduled on the 18th floor of a high-rise flat—the kind that have been cloning themselves lately across London’s less developed boroughs. Remu, an acolyte of Burna’s, asks me and a radio DJ—it’s press day—what we want to drink. My request for tea is met with titters from the DJ and brief befuddlement from Remu. I accept a Hennessy and Coke instead.

Usher’s new Hard II Love album and chatter is coming from the living room, pouring out every time the door is opened. In and out go different faces, more acolytes and his large orbit of friends and hangers on.

Burna’s press team show scant interest in the questions I show them. The aim, I sense, is to check for anything that might rankle. Burna Boy’s list of controversies with his label Aristokrat Records and the media has brought him untoward attention.

The intro to his sophomore release, On A Spaceship, is an interview clip given by an uncredited media personality who insists that the controversies—threatening to kill bloggers, fights with other artists, quarrels with producers over allegedly unpaid royalties, posting pictures of guns on his Instagram—will not only derail his career but probably put an end to it.

No such thing has happened yet. Burna Boy’s career appears to have reached new heights in terms of the maturity of his music and international appeal if not recognition. Redemption's only recognisable hit is "Pree Me," the lead single which will no doubt anchor the project upon its release, but will also belie the most interesting parts of the EP. It starts with a plangent piano loop laced with Burna’s rich baritone.

That voice is a potent weapon in an already impressive arsenal of talents that include a rare instinct for not taking different genres and harmonising them all into one song. "Boshe Nlo" is one such song. The intro is a sped up chant in Jamaican patois, the first verse is in pidgin, the chorus is in Yoruba and the adlibs on the second chorus is an import from Fuji, the Nigerian genre whose most prominent purveyor is King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal, KWAM 1. Later on in the song he harmonises in a falsetto, a flourish that holds my attention in any song.

On "Body To Body," the first line of the first verse sounds like a riff off Craig David’s "Fill Me In" and ends in a cadence that is as much R Kelly’s as it is Jagged Edge's. On "We On," the first two couplets are reminiscent of Tracey Chapman, the second could be pegged as The Weeknd’s and the chorus, when it comes, has the nasal drawl of Future.

These influences are not deployed wholesale, rather they are riffs, snatches of melodies, tools used to articulate Burna Boy’s own musical preoccupations (unifying genres) so much that he becomes a shapeshifter in the truest sense. When Drake, for all his gifts, makes a dancehall track ("Controlla") or adopts Black British “Ebonics” ("Back on Road" off Gucci Mane’s Everybody Looking or "R.I.C.O" off Meek Mill’s Dream Worth More Than Money), it is clear that it is only an excursion he's embarked on, and that soon after, he'll be back to Toronto.

In Burna Boy’s case, it is not a format he adopts for a particular song. The flow comes from inside, a part of which he simply taps into rather than borrows, however adroitly, to expand his sound. If indeed he is the shapeshifter I believe he is, the many rivers of influences must run deep inside of him and beyond the music.

I mentioned this to Burna Boy, not as a question but as an observation and this is what he said:

Man, the truth is music is a universal language. It's something that I've always been told, but it's real. You see me. I'm well traveled as well, so I speak a couple languages. My mom speaks Spanish, German, French, everything. Me, I understand French, hear me, understand a couple of Spanish, even Portuguese.

You also did some of your growing up in Brixton?

Coming up from Brixton and that, that's where the whole Jamaican influence comes from, really. Obviously, I'm from Nigeria. That's another culture on its own, so what brings it all together for me is music because music, I can listen to Jamaican music. I can listen to Indian music.

"Boshe Nlo" is a marvel of a song. By the second chorus, one has heard Jamaican Patois, pidgin, Yoruba and Fuji in particular. It's not disjointed but wholesome. We've never heard that before.

Yeah, that's what I'm trying to explain to you. Man like me, you should understand that I don't see black and white. Hear me? I don't see straight lines. I don't understand the concept of straight lines. There's so many ways.

That's partly why I didn't get your music at first to the point of being resistant to it. An ex-girlfriend would play it in the house and I remember telling her that you're cheating—which she didn't like—partly because I couldn't place you in one tradition or genre. Even when I know better than to box an artist, the temptation is too easy. Where is the centre?.

Oh, the centre is crazy. The centre is music. Music is life. This is the real reason I called the first album Leaving an Impact for Eternity, apart from the abbreviation and all that because life is music, man.

There is a trace of Tracy Chapman in "We On."

You know the truth? I've only heard one Tracy Chapman song in my whole life.

That's the craziest thing I've heard all week because when I heard it, it was unmistakable. But it's also possible that I'm trying to somehow understand a voice that I've struggled to accommodate in my “audio-sphere” since I was a child in Kaduna (Nigeria).

I've heard one song from her. I don't even know if it's a her or he.

It proves that some of the influences people pick up in your music is sometimes imagined, a false recall that can be indistinguishable from the real one. It proves the theory which is that you're the “perfect human synthesiser.” Yes, you pick up all these influences but when they come out, the product is unmistakably yours. Do you even care about some of the musical connections that people make on your behalf?

Most definitely because, you see, without the old, there is no new. At the end of the day, man, any tree that doesn't have roots will fall, fam. Man like me, I've got musical roots that go everywhere. My roots go far and wide.

Is it confined to the musical or has it affected other areas of your life?

It's both.

Yes, but how deep? Does it dictate who you date or what you eat or how you see the world?

Man, when you've seen stuff that I've seen, you realize that everything in the world is actually the same but in different ways. Everything and everywhere is actually the same, but people just have different ways of going about things. I feel like, if I make a song in Nigeria about how there's no money and there's no light and if I talk about it, police will come and stuff like that.

Somebody in America can relate to that. I'm not from America, but they can relate to exactly what I'm saying, and they go crazy even more because the way I'm saying it is not the way they're used to, but they know what I'm saying. Because it's a spiritual ting, if you know exactly what I'm saying.

If your mom suffered from cancer before and you hear a song and then I'm speaking in Yoruba about something about cancer, automatically, your spirit will feel it like, "Damn."

True.

Yeah, so at the end of the day, that's music, generally, and that's life as well. Life is way bigger than just staying in one place and thinking that's about it. No, the world is small but it's huge. What makes it small is the fact that we're all the same. Do you understand? What makes it huge is that we have different ways of going about things.

Leriq produced the entirety of Redemption. I feel that his spirit has to be as open as yours if he is to accommodate the different traditions you draw from.

We both have troubled souls, man. I don't know how to explain it. It's because we don't see colors, man. We just don't see colors man. We don't see straight lines and that's what we have in common. That's really it. The music is just bound to be magical because when two souls that feel the same way about something, even though they don't feel the same about nothing. It's magic.

How far does that relationship go? Do you hang out together? What would you do, typically, when you're not recording?

We're literally just talking so much shit and just laughing and talking shit. Trust me.

Where was Redemption recorded?

At my house and West PD studio. That's the Aristokrats’ CEO.

How much has that changed since when the two of you recorded your first album L.I.F.E?

Everybody's richer now.

Yes but how have these improved conditions like fame and money affected how you record music? Does it have any real effect at all?

Doesn't change anything. No, because, really, what we would do with the money. We just have fun. Buy more equipment and stuff, so we just do it the same. We're just, pretty much, doing the exact same thing, living the exact same life, we're just wearing bare clothes and stuff like that.

So there’s no real effect from the fame or success on the actual recording part?

No. Obviously, sometimes, there's times where niggas throw money on the studio floor and that's just to get the hype type shit. Now, niggas can do shit. Obviously, to me, it's only made everything better because it's not like we're driven by money, we're like, "Oh, we have to record this song to make this money." No, man. Really and truly hear me that we don't always have money. There's times when we don't have any money and we're just chilling and shit, but it's still the same shit.

Burna's Mom

Being the grandson of Fela’s manager does have its perks. As a child, Burna’s mom, Ms Ogulu who on interview day is regal even in beige dungarees and house slippers, grew up in the a time when live music flourished in Nigeria. Her father, Benson Idonije, was Fela's manager.

I take it you had a very musical background.

Yeah, a lot of the influences came from my father, who had a jazz background, who didn't say this to him but used to say to me that if you cannot read and write music, you are an illiterate. You know, I didn't say that to them (all three of her kids of which Burna is the first). Yeah, I didn't say that to them but I had a language school and a music school so you know, for me, the essential thing was to let them go through it and be well rounded individuals.

Did Burna take to music early on?

He's a natural, he was a natural for physical sport. He became a black belt at 11. Anything that had to be done in water, he was perfect. First it was football then it became all about basketball. Then the art, he’s a wonderful visual artist, he draws and he actually taught his sister how to draw. Today, she’s also a musician but she started out as a visual artist (Her stage name is Nissi). She’s had exhibitions in various spaces.

Does all the negative press he gets worry you? Because you know what's false and what isn't.

Not anymore because at the end of the day, everyone is trying to make money. So it's not about whether it's true or false, it's about doing their jobs properly. My father was a journalist for 35 years. He still is. He writes at least 2 articles a week for the Guardian (Nigeria) newspapers. Until today and he's 80 years old and he's just launched three books. So I've come to realize it for what it is. There's a bit of laziness, there's a lot of incompetence, nobody wants to look for real news. We've even lost the value for real news. Journalists are a lot lazier. Most of the information that you get now are from the Instagram pages of celebrities, I can never get used to those things. The professional ethics don't exist anymore because the people don't even know them. Yes, so I mean I don't worry anymore.

It must be frustrating for him to be miscast in the press time and again. How has all the attention, both good and bad, affected him when he's not in front of the camera?

Thankfully he is doing well. It would be worrisome if you walked down the streets and you're not recognized. It would be worrisome if people don't want to interview you. It would be worrisome if you're left completely alone, I mean yeah, sometimes, I do wish I could just take him somewhere because he just wants to be himself and he's not allowed to. Most things that his peers get away with he can't. He was taking a walk today, he went down and was taking a walk and everyone went after him screaming, why are you walking around alone? He said I just wanted to take a walk.

On Performing Live

The conversation with Burna later moved on to live performances which, despite the ascent of afrobeats, is in a dire state. This is understandable because most artists start out independently and on small budgets that are used to create or pay for a hit song(s) that will then generate money for even better beats and videos. This money is generated through performing at show after show, all done with little or no experience of how to command a stage and work a crowd.

Burna has at this point done lots and lots of shows. That said, his first London date is a significant one. The city has an unfair advantage as being, what some will disagree, the cultural capital of the English speaking world. Every band, fledgling and established, wants to tick it off its tour calendar. Another reason is that a crucial part of Burna’s development, as man and artist, was spent here in London, which is why it is billed as his “Homecoming Concert”.

Do you remember your first live performance? What year was that?

2011.

Do you remember what songs you performed? How did it feel being on stage for the first time? What was the reception like?

The songs were "Abeg Abeg Abeg" and "Wombolombo." Those two songs, they're very big in the south side of Nigeria, that's Port Harcourt. It was some real stuff. They were flogging people off the stage but, me, obviously, I had my own fans so it was mad for me.

Is that the same show where the crowd wanted you on stage even when the Mo Hits crew (ledd by Don Jazzy and D'banj) were about to perform? You lit up when you spoke about this episode in your interview on Olisa TV.

That's my city, man. This was in 2011 and Port Harcourt is my city, man, at the end of the day. They didn't want me to perform because it was mad political and all types of stuff.

Mo Hits were the biggest pop group in Nigeria at the time.

Me, I was like, "Cool." I didn't really care, to be honest, but, obviously, my management and everybody at the time were like, "No, this guy's performing it." The crowds, they're calling, chanting my name or screaming my name. I had no choice. My manager at the time was really pissed off about it. Me, I was just sitting down when they said I should perform. I did "Abeg Abeg Abeg" but the crowd wanted me to do "Wombolombo." I told them I was only allowed to do one song. Everybody was like “we go tumble here.” That made everybody be like “who's this guy?”.

I find it interesting that you didn't care whether or not you got up to perform. You really didn't care?

No, because you see me, man. I really don't care about anything. I just take life as it comes, hope for the best, prepare for the worst.

We are polar opposites. Do you remember how you felt? After all that happened and you finally got on stage for the second time?

It was a realisation process for me because that was when I knew that rah, this is real.

How old were you at the time?

I was 20, I think. Yeah, I was 20.

The crowd preferred you to the biggest label in the country. If you needed any confirmation that you were good, that must have been it. Let's talk about live performances which I think is in a dire state in Nigerian pop. It was the same with hip-hop where you record a song which breaks out and becomes a hit. So you now have shows lined up with little or no experience of performing live. It's understandable, the problem, but it's still a problem especially in afrobeats right now.

(Laughs) Man, the truth is, man, everything is not for everybody. I keep saying this. Everything is not for everybody. Everybody does what they can. You can only do what you can. You can only try. See, in Nigeria, it's not easy to say you're a live artist. Do you understand? It's not easy to make that decision. You get me? Men like me, I came up on the live performing. That's been my thing. I would freestyle for the man-dem daily. You understand that? I had to figure out ways to impress man-dem there. That's just how it is. Not everyone has that background. My granddad is a manager as well, so I've been watching the live performances since I was a kid. It's like proper Nigerian live performance is like Fatai Rolling Dollar, all types of stuff.

You have to perform live. That's where it is.

Yeah, man, that's what it is. My granddad tried to make me play all instruments if I said I wasn't going to do music.

Can you play any instruments?

I mean, I can do a little bit of a lot of things, but I cannot say I'm a pro at anything apart from singing stuff and making music.

Is there any real artistry in performing live that is of value to you when you return to the studio?

Of course. Every song I make, I try to imagine how it would feel performing it in front of a large crowd because at the end of the day, you see, with me, I'm saying so much with my music. I'm actually showing you what's going on, even though you're dancing to it, at the end of the day, when you sit down and listen to it on your own in the dark at night one day, you realize, "Whoa, this guy's actually saying some real shit."

I experienced that with the EP

Yeah. Basically, with people like me, on stage, I'm thinking, "Rah, okay if I do this on stage and they don't sing along with me and they cannot sing along, at least I can stop the music and say what I said in the tune." The same way I said it on the tune live a cappella so they hear exactly what I'm saying. Somebody would be like, "Fuck, this guy's the realest."

Is that - stopping midway through a show to speak to the audience - something you developed or is it something that you picked up somewhere?

It's something that I've always done because I just hate being misunderstood, because I've always been misunderstood. I actually hate it but it's something I've had to get used to. If I'm going to be misunderstood everywhere else in life, I will not be misunderstood in my music, especially the actual music. Anyone can say anything about me, but they will never say, "Oh, his music is shit."

What would the best way to experience your music be?

It has to be live. That's the best way to know who I am as an artist. It's live because live, you get the real organic feeling. I don't have to explain it to you.

So you feel you're more of a live performance artist than you are a recording artist?

Exactly.

And is the recording just a pathway to being on stage?

Exactly, because most of my songs that I used to perform ... I hadn't even recorded them. I performed it before I recorded it.

Tell me a little more about it.

Basically, this is what happens. I go to the studio, they play a beat. I spit, spit, spit, and then they just take what's nice.

It's that simple?

Yeah, just take what's nice and it's done. You understand? Basically, with that, there's just so much going on in my head. Do you understand? Basically, sometimes, the maddest of all my tunes have been freestyles that are recorded on the phone, just as like this interview.

Can you tell me one or two of them?

Let me start from the beginning. Tonight was just, basically, we're just chilling. Everybody's chilling on a normal day, and then this guy, Lere, he had his phone on and stuff. Yeah, man. That's how that song came. Then, they made me record it like that. You have to record this tune here. You understand?

How do you prepare for shows, especially one as big as your October 1st date at Hammersmith Apollo? Do you have a process?

Man, I've done too many shows in my life. This is what I do, man. Yeah, I just got done performing for 50,000 people in Markudi [Benue State, Nigeria].

So the 5000 tickets for the London date is nothing, even though the buildup is of what looks like your biggest show yet?

Yeah, why it's so huge is because I haven't been in here in seven years. Obviously, the buildup has just been crazy. Nobody in London has seen me on stage.

What's the most memorable live performance you've ever seen?

I went to watch 9ice perform in Calabar [Cross River State, Nigeria] one time. When I first got back to Nigeria [from London]. Bro, it was mad.

At what age was this?

Man, it was still around when I was 20. It was 19, 20. 19, definitely. I was 19 and then I watched 9ice perform. That shit was crazy because that's when I knew that, "Yeah, man." I used to think my voice was kind of shit. But them man there - Mark Morrison made me think like "Rah, my voice actually mad."

I was thinking Horace Brown. When 9ice came out with "Gongo Aso" and "Street Credibility" with 2face?

It was a Calabar kind of carnival at the time. It was mad. Trust me, it was crazy.

The London Performance

On Youtube is a 15 minute clip of Burna’s appearance on Westwood’s Afrobeat Freestyle session. As is the custom on the show, Westwood drops successive beats over which the artist freestyles changing cadence and style. For some, it's an opportunity for showboating, for others, it's an honest display of lyrical dexterity and versatility. Or both.

Westwood’s beats for Burna ranged from a trap beat (what used to be strictly slow jam), to dancehall (Actin Bad), to Afrobeat (Wizkid’s Ojuelegba), to another slow jam, to the beat for Drake’s Controlla (over which he sings a verse off Pree Me), to briefly breaking down, overcome by a tribute to a dear friend, Gambo, who has passed (and whose face he has tattooed on his belly) to trapping on a dancehall beat, a flourish I was hearing for the first time.

This fifteen minutes is the final reason I became a believer. One could cheat in a studio modulating voices and sounds, but not live and in front of cameras and not when beats of different tempos and traditions are thrown at you. It's a beguiling watch. There is no fakery or insincerity. The same focus that is brought to one sound is applied to another. If I was looking for a centre, by now I'd given up on the search because there is no centre, which is not the same as being empty, rather it's the wrong place to look. When he says that he's doesn't see straight lines, he means it.

Sabo Kpade is a sifter for the SI Leeds Literary Prize 2016. He’s been shortlisted for the London Short Story Prize 2015 and was a finalist for the Beeta Playwriting Competition 2015. You can follow him on Twitter @Sabo_Kpade.