Bisa Butler Summons Black History In Her Quilted Arts to Motivate the Fight for Black Lives

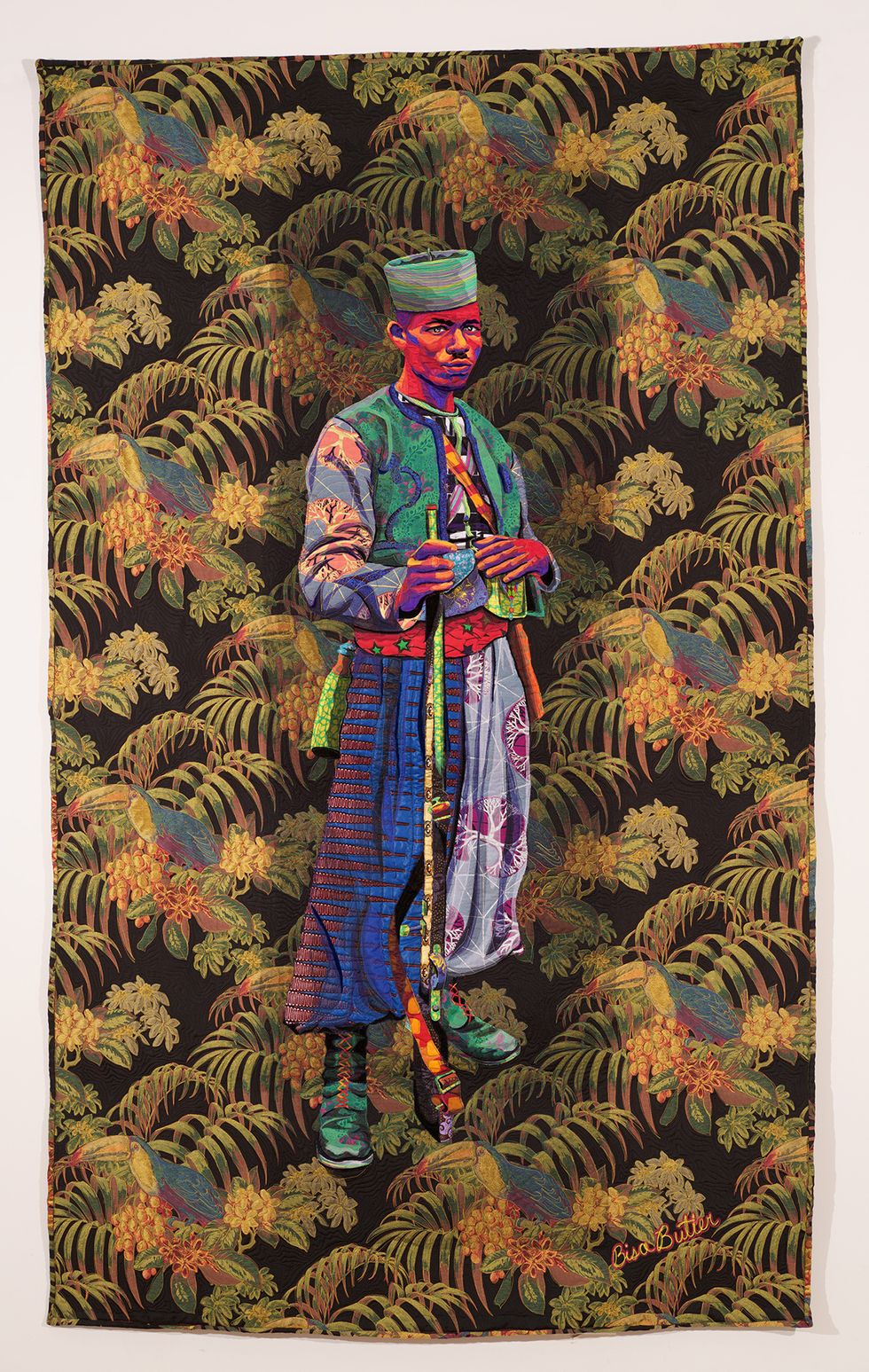

The artist draws on vintage African and African American imagery to create quilted portraiture that is a "celebration and an affirmation of Black life."

There's a lovely tradition that exists of artists who are African by lineage, but born and bred in the diaspora creating art by summoning the continent as a source of motivation and inspiration in order to tell the myriad stories that exist about Black culture, heritage and history.

Amongst these artists is Bisa Butler. Born and raised in New Jersey, Bisa is prominently known for the portraiture of her quilted arts. Bisa pulls from a rich cultural heritage with her use as quilts as a medium that portrays the visibility of Black history, Black essentiality and Black growth in various sectors of life.

In Bisa's artwork , color is a language that speaks about African American evolution from enslavement in the United States to today's ongoing fight for Black liberation Bisa also draws on her Ghanaian heritage by illustrating the vibrancy of Africa's textile and fabric traditions. These artistic methods allow her to examine several themes including family, community, youth and power.

OkayAfrica sat down with Bisa Butler to discuss her background and career as an artist, her works and how the recent pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement has affected her space and imagination as an artist.

Can you tell me your background as an artist and how you discovered art?

I have been creating art for as long as I can remember. As a child I was always drawing and painting and my parents encouraged my interest. My father was a college president for 37 years here in New Jersey, and my mother was a French teacher. They both valued education but they also had a respect for the arts. They made sure I always had plenty of art supplies, and would take me and my siblings to museums.

I come from a family of people who sewed; my grandmother, mother and all 6 of her sisters knew how to sew. They were not quilters but were like many baby boomers who sewed out of necessity and to enhance their homes and wardrobe. My mothers family was international and grew up between Morocco and New Jersey (my grandfather worked for the Foreign Service.) They saw Paris fashion magazines and designers and used their sewing machines to create cutting edge fashions in the 1960's. This influence caused me to be interested in fashion and sewing in college in the 90's, although I majored in painting. I was struggling to find my own voice with my paintings when my professor suggested that I start incorporating the fabrics that I wore and designed into my paintings.

By the time I graduated I was gluing more and more fabric to canvas, and then while studying for my masters I had an assignment to make a quilt that changed my life. I made a quilted portrait of my grandparents, and I have been quilting ever since.

Your work is rooted in Afro essentiality and Black history. Can you tell me about it?

My art is a representation, a celebration and an affirmation of Black life. I am using vintage photographs of unnamed Black people and celebrating them in a way that should be done. I want to show the world who we really are; we are people of grace, of dignity, or pride, of love. We are beautiful and we are human beings who not only deserve to live; we deserve honor. If people walk away with one thing when seeing my images, I want them to see a reflection of humanity and realize that this was always there- if you take the time to look.

I want to give my people something that they may not have had in life, or at the very least give the respect they deserve. If my subject is barefoot because they live in poverty, I look up the shoes of their time and give them a nice pair. If their shirt is worn and torn, I fix it. I think about them like people we know now— everyone wants to look good.I have made portraits of famous people such as Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X and Nina Simone but I prefer to highlight ordinary people who don't get as much attention.

Color, textile and fabric play a fascinating role in your work . Can you tell me why you use them?

The African American community has always used colorful language to describe our complexions. A person with very light skin is called "yellow" or "red boned" if they blush easily. A very dark skinned person can be referred to as "blue-black."

I use color to communicate emotion but also to speak to the African American tradition of using rainbow toned colors to describe complexions. Many of the names used to categorize African American complexions were used to determine a person's lightness or darkness during the slave era. If an enslaved person was of a lighter complexion they were most likely a child or relative of the Masters and slavers— that person would be privy to an easier job and a more comfortable living condition. Light skin became a signifier of a less brutal existence although that many times wasn't true. I create my figures in a myriad of tones to deliberately blur that line from light to dark. My figures must be understood on their own but not in terms of light or dark. The colorful tones I use speak more about emotion than actual complexions. Unfortunately some people still value light skin over dark skin and I refuse to play into that with my figures.

Many of the prints that I use have specific meanings. The manufacturers send their fabrics to be sold in the open air markets in Africa where the local women name them based on what the patterns remind them of in their culture. For Instance a fabric that has images of a grade school primer on it is called " ABCD " and men and women wear it to symbolize that they are literate and value education. A fabric called "Jumping Horse" is used to symbolize the phrase " I Run Faster Than My Enemies'', or in other words; the wearer triumphs over adversaries.

I use prints like these to reinforce the narrative I am trying to tell with my portraits. I used the ABCD print on a portrait of Frederick Douglass to communicate to the viewer that education and literacy were vital to him— he forged his own free papers and was able to escape slavery because of these skills. I also use silks, lace and velvet which are traditional dressmakers fabrics because those are what my mother and grandmother used. I find that the types of fabrics help me communicate ideas; lace can make you think of something delicate, denim can make you think of durability, and silk satin may make you think of wealth and opulence.

Image courtesy of the Claire Oliver Gallery

Bisa, your arts also tells many stories about culture. From which cultural background do you make your art?

I am an African genetically and culturally—my father was born and raised in Northern Ghana, while I am also American. My mother was born in New Orleans and was raised in Morocco because my grandfather worked for the US Foreign Service. I was raised in New Jersey.

My work is traditionally African American but my motifs, symbols, and color choices can be traced back to Africa. Quilting allows me to connect to my matrilineal tradition of sewing and collecting fine fabrics, while it also connects me to my patrilineal ancestral legacy in Ghana. I use primarily Dutch and African Wax printed cotton, Ghanaian kente, Nigerian aso oke, and South African shwe-shwe in my artwork.

I start each piece of art with the intention of honoring someone from the past. There are tens of thousands of photos of African Americans and Africans that have been taken over hundreds of years as postcards, as studies, and as documentary photographs. Most of the subjects are Black people who are unnamed and unidentified. Many times the only title given to these photos will read something like "negro man, Mississippi Delta." I feel compelled to reclaim these images, make them life sized so they look us (the observers), directly in the eyes. I look at the images carefully and study them trying to bring forth the personality and spirit of the sitter. Are they looking shyly? or perhaps they have a bold direct gaze and stance. Some of these images have languished in files for over 100 years and I think it is about time someone paid attention to them.

Has the current pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement affected the imagination and space you create from as an artist?

This current pandemic and the protests against racial injustice have affected me in ways that will still be playing out years from now. The coronavirus hit New York in the first week of March and my first solo museum exhibit was set to open March 15th. By the time the 15th had rolled around New York was being quarantined and the rest of the boroughs and states followed soon after. I was devastated to say the least. All of my hopes and dreams for my major debut were hijacked by the first pandemic I had ever experienced. The virus hit New York and New Jersey like poison gas. I know countless people who have passed away. A dear friend of mine was a young mother of a toddler and is now gone. Although the peak has passed, another friend's father just passed away just yesterday. The virus has not finished ravaging my community.

I first started making quilts when I was in mourning after my own dear grandmother was in hospice. I tried to paint her and failed miserably and then created a quilted portrait for a class project. The making of the quilt was healing for me because I could use fabrics that she had given me. I could use techniques that she had taught me. The quilt was soft and warm and I needed comforting at that time. I find that I need this comfort again and now I have the ability through social media to share that comfort with the world. I have turned to creating images of hope and family now, more than ever. It seems that I and my community need to be reminded that this too shall pass.

George Floyd was murdered on May 25th by a police officer kneeling on his neck until he suffocated. The US erupted in outraged protests. My artwork has always been about honoring and allowing my people to be seen. Now more than ever that is important when so many white people are coming to terms with the fact that they had been willfully ignoring the plight of Black people. This ignoring of a whole race's suffering has allowed us to be harassed, and murdered by police, forced into poor neighborhoods, offered sub-standard educations, unequal healthcare and disproportionately killed by COVID-19 in shocking rates. White people who care are paying attention and this has put a lot of attention on me and my fellow Black artists. Black people need solace and to see positive images of themselves. White people seem to be interested in seeing positive images too, images of people they may have ignored before. I am carrying on as I was before; celebrating the ordinary, highlighting the beauty of Black people but my audience that was once primarily Black is now mixed. I want everyone who sees my work to see the soul and humanity—to realize and understand. We are people, and our lives matter.

- In 'Aba Women Riot' Nigerian Artist, Fred Martins, Reinterprets a ... ›

- How Fashion Historian Teleica Kirkland Is Transforming What We ... ›

- Spotlight: Adekunle Adeleke Creates Digital Surrealist Paintings ... ›

- Spotlight: O'kiins Howara Creates Technicolor Images of His ... ›

- Spotlight: Akintayo Akintobi's Impressionist Paintings Are Steeped in ... ›

- Spotlight: Artist, Ngadi Smart, Captures Black Sensuality, Sexuality ... ›

- How Sudanese Art Is Fueling the Revolution - OkayAfrica ›

- Taking Back Our History: Understanding African Art Repatriation ... ›