Closure of Popular Publisher Raises Questions about the Future of Literature in Zimbabwe

After 25 years, Weaver Press has closed its doors — leaving a massive hole in the Zimbabwe literary community.

When Alison Tinashe Muzite read Writing Still, an anthology published by Weaver Press as a student, he dreamt of having his books released by such a reputable and traditional stable. But 24-year-old Muzite’s dreams were shattered after Weaver Press, a publishing house run by Zimbabwean couple Irene Staunton and Murray McCartney, announced that it was closing — after just celebrating its 25th anniversary in December last year. “It is painful,” Muzite tells OkayAfrica. “I have some manuscripts of my poetry anthologies I have been writing for the past half a decade which I wanted them to consider.”

Piracy, lack of funding, self-publishing and social media, are some of the reasons why Staunton says they made the difficult decision to shut down.

Bringing many authors to the limelight

Based in Emerald Hill, a leafy suburb in Harare, Weaver Press published a diverse range of literary works, including novels, poetry, history, short stories, anthropology, memoirs, and environmental studies.

Weaver Press played a pivotal role in growing Zimbabwean literature, bringing many authors to the limelight. Named after the weaver bird, the publisher has released the works of about 80 fiction writers including Zimbabwean American actress Danai Gurira, Emmanuel Sigauke, Yvonne Vera, Chenjerai Hove and Gugu Ndlovu.

The Stone Virgins, published in 2002 and written by the late Zimbabwean writer Vera, is one of the notable books published by Weaver Press in their early days. The book, which paints a picture of Zimbabwe’s transition from colonial rule to independence and the brutal civil war that followed under dictator Robert Mugabe, was the winner of the Macmillan Prize for African Adult Fiction.

Another notable Weaver Press title, We Need New Names, the debut novel by NoViolet Bulawayo, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2013, and won the prestigious Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for debut work of fiction, as well as the Los Angeles Times Book Prize Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction in 2013. Bulawayo became the first Black African woman and the first Zimbabwean to be shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

Ignatius Mabasa, a poet and writer, says Weaver Press was a “serious” publisher. “I mean they did not just publish books. The books were of high quality. Thoroughly edited,” adds Mabasa who was featured in the Writing Free anthology — which was edited by Staunton, and published by Weaver Press in 2011 alongside other writers like Bulawayo.

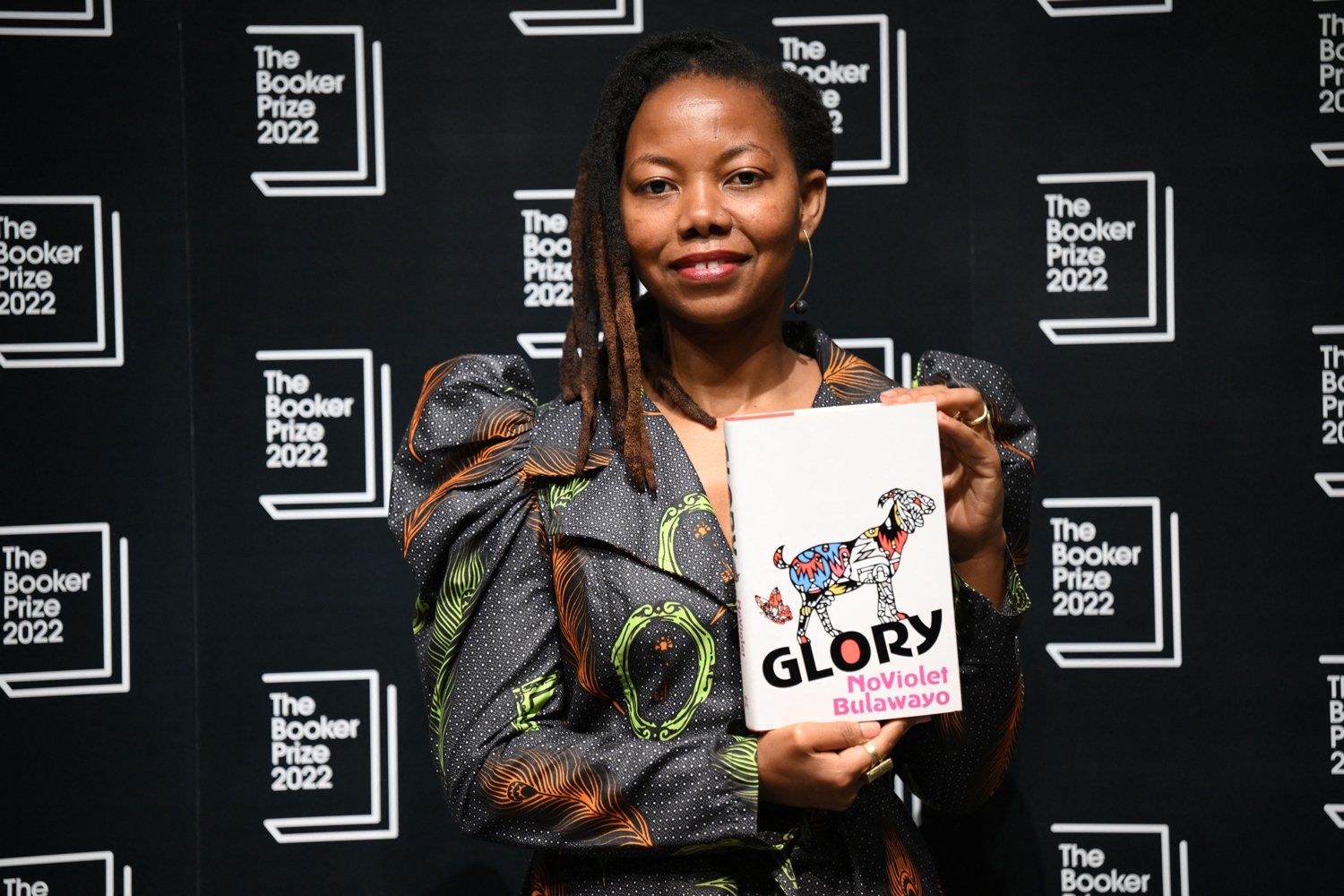

More recently, Glory, Bulawayo’s latest book dubbed “Zimbabwe’s Animal Farm,” which shows a country imploding after the disposal of Mugabe in a military coup in November 2017, was also shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2022, making her the first woman to have her first two novels shortlisted for the prize.

Just like George Orwell’s seminal novel, Glory is narrated by a chorus of animal voices, bringing to light the authoritarian tactics employed by dictators to consolidate power.

Zimbabwean authors’ challenge in the digital era

Having survived Zimbabwe’s economic malaise characterized by hyperinflation, poverty and high unemployment in the 2000s, Weaver Press cannot take it anymore, with pressure from digital technologies heightened by the current economic crisis.

Staunton says the publishing scene has changed greatly over the last two decades. “One could argue that a small independent publisher has become something of an anomaly at a time when everyone who wants to write can self-publish and social media plays such a significant role in what people value and how they spend their time,” says the editor, who has been in the publishing sector for almost 40 years.

“In a country where many people struggle to survive, book purchase is not a priority, unless it is an essential textbook needed to pass an examination.”

Weaver Press was one of the few remaining traditional publishers focusing on literature as other publishers, like College Press and Zimbabwe Publishing House, are mainly focusing on textbooks for schools.

Staunton says piracy is also threatening the literature sector, coupled with younger generations relating more to watching than reading. “There is little or no government funding for libraries and most schools do not encourage people to read with well-stocked libraries and free-reading periods,” she says. “In other words, reading for pleasure or to stimulate one’s ideas and imagination is not encouraged in our young people.”

Award-winning author Phillip Kundeni Chidavaenzi, says the closure of Weaver Press, sad as it is, is not surprising. “Quite clearly, the operating economic environment in Zimbabwe, not just for publishers, but every other business, is crippling,” says Chidavaenzi, author of Chasing the Wind, independently published in 2021.

As Mabasa adds, the role of literature goes beyond entertainment; it keeps a valuable record. “You can go back to literature and tell what happened at a certain time based on the setting of the book. Literature should be seen as an industry,” he says.

What is next for up-and-coming authors?

As it stands, some authors struggling to get returns in Zimbabwe are looking to foreign publishers in the United States, South Africa and the United Kingdom. However, Staunton says the best way young writers can help and support each other and the publishing industry is to buy each other’s books, and not just read them but actively debate and honestly critique them. “Publishers cannot survive unless people buy books. And all our best writers have also been avid readers,” she says.

Chidavaenzi says the future for the literature community in Zimbabwe is bleak. “Over the past few years, many writers have been turning to self-publishing, which is affected by the reading public’s perceptions for the simple reason that it lacks the editorial rigor and refinement associated with conventional publishing houses,” he says.

Nonetheless, some seasoned writers believe that turning to digital is a better option given that high quality is maintained. “We can explore digital which is not as expensive as publishing physical books. But then quality is important. The books must go through a rigorous process. There is a need for gatekeepers to make sure the story makes sense and to proofread,” Mabasa says.

Muzite, whose poems were featured in Not Forgotten; Remembered with Love, a poetry anthology on mental health, published by upcoming independent publisher Ruvarashe Creative Writes in 2023, says he is looking into self-publishing but financing the project is a challenge.

Mabasa says some writers who self-publish their books have fallen by the wayside because of rushed manuscripts and poorly edited books. “As things stand now, we are in trouble,” he tells OkayAfrica.

Staunton believes that everyone involved, like the education system, municipal and university libraries, vibrant, well-stocked bookshops, and an interested and committed reading and book-buying public, should come on board to save the industry. “McCartney and I are not getting any younger. It is time for fresh energy and new ideas,” she says.