The Weeknd is Helping Bring Back the Ancient Ethiopian Language of Ge'ez

The Weeknd put out his third album last week. What most don’t know is that he’s also helping bring back the ancient Ethiopian language of Ge’ez.

Most people don't know that The Weeknd is helping bring back the ancient Ethiopian language of Ge’ez.

In the months leading up to Starboy’s release, the Toronto superstar spoke openly about the record’s influences, from the late Prince, Michael Jackson and the original Starman, David Bowie, to The Smiths, Bad Brains, Talking Heads and, of course, Abel Tesfaye’s Ethiopian heritage.

Speaking with VMAN, the singer revealed that Amharic would “definitely be key” on the new record. Whether or not this is actually the case is up for interpretation, but we do know one thing for certain: there was one more Ethiopian language on Tesfaye’s mind around the time he was working on Starboy.

In July, Tesfaye donated $50,000 to help establish an Ethiopian Studies program at the University of Toronto. (This was in addition to the $250,000 he donated to Black Lives Matter.)

1 - sharing our brilliant and ancient history of Ethiopia. proud to support the studies in our homie town through @UofT and @bikilaaward

— The Weeknd (@theweeknd) August 6, 2016

His contribution went towards a fundraising initiative launched by University of Toronto Professor of History, Michael Gervers, with the support of community leaders from the Bikila Award, a Toronto-based not-for-profit named after Ethiopian Olympic hero Abebe Bikila. It was the Bikila foundation that approached Tesfaye about getting involved in the cause.

“Because of his reputation, [the campaign] was picked up quite broadly by the media,” Professor Gervers mentions of the singer's support.

Of course, Tesfaye was one of many Ethiopians in Toronto instrumental in making the university’s first Ethiopian Studies program a reality. The role of the Ethiopian-Canadian community cannot be understated.

The campaign was ultimately a success. And in January 2017, the University of Toronto will commence its first Ge’ez course through the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations. The class is also a first for North America.

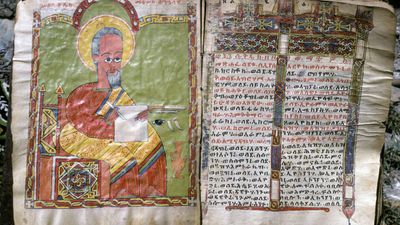

“Without Ge'ez, there's no way we can get anybody to comprehend what is written on these literally millions of parchment manuscripts,” explains Gervers. “In other words, the real study of Ethiopian history and society cannot take place until people can read Ge'ez.”

We recently spoke with Professor Gervers to find out more about Ge’ez and the Ethiopian community that rallied together. Below is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

How did the Ethiopian Studies program at the University of Toronto come about?

I started working in Ethiopia 30 years ago and the project I have been involved in with other colleagues from Europe is to document cultural and artistic history in Ethiopia. This has been largely to do with the architecture of the country and what we call the ecclesiastical paraphernalia. Anything which is old and has survived, from manuscripts to crosses to incense burners.

We're particularly interested in preserving manuscripts because there's so many of them which are not currently being read except perhaps by the priests who were in Ethiopia, because Ethiopians themselves do not normally learn how to read Ge'ez.

At any rate, about 15 years ago, I began giving a course at the University of Toronto on what I call the Social History of Ethiopia, where we covered some of this material and I illustrated it with photographs which I took myself. I have a large database of photographs somewhere in the neighborhood of 70,000 images which we use as a resource for the course.

Hamburg University has a very extensive program in Ethiopian studies as a research center and teaching center. Over about the same period of the last 15 years, they have put together this extraordinarily useful Encyclopedia Aethiopica. At any rate, they have a five-volume encyclopedia which many of us have contributed to. I supplied them with a good number of the photographs which they used to illustrate those volumes. So that's one side of it.

Secondly, there's a small team, headed by myself and a colleague in Sweden, Ewa Balicka-Witakowska. Since about 2005, we have attempted successfully to digitize hundreds of Ethiopian manuscripts largely in church repositories. One of the main ones that we've digitized was from the collection of the monastery called Gunda Gunde which is in the North, not very far away from the Eritrean border. There are 219 manuscripts and 35,000 pages of Ge'ez text that the University of Toronto is currently making available online.

We have the photographic resource and we have this very, very rich collection of digitized Ge'ez text. There are other institutions putting material of this sort online, but nowhere as extensively as here at the University of Toronto.

With that, and this is something which I would really like to make public, is that we have a very active community of Ethiopians in Toronto and Canada, not to mention in North America as a whole. Toronto has been very active with the foundation of the Bikila Award.

In September of last year [the Bikila Award] invited me to come speak to their group. It was at that time that I said, "Listen, I'd like to see something happening in a serious manner at the University of Toronto in terms of Ethiopian studies."

The reason I brought this up is that we have a number of immigrant communities in southern Ontario and particularly Toronto—people like the Poles and the Hungarians and particularly other European countries—that have raised funds for a teaching program which concentrates on their home area. So I suggested to the Ethiopians that they should do the same thing. I said I put down the first amount of money to do that and I challenged them to raise this money, and they responded immediately.

I had this meeting with them in September, and December of last year they held a meeting and in a couple of hours’ time they raised $30,000. That was really a definite shot in the arm. And it was last summer in July that they got in touch with Abel Tesfaye, who is the person behind The Weeknd. I don't personally know who got him in touch with Bikila, but they're all Ethiopian and Tesfaye is from Toronto so he apparently wrote them a check for $50,000. Because of his reputation, it was picked up quite broadly by the media.

Tell us more about Ge’ez...

As a university professor myself, I recognize if you want to do original research you have to be able to read the language of the area in which you're doing that research. There is very little in North America, and in fact I couldn't tell you anywhere at the moment, that really has a formal program in teaching Ge'ez. This is what I proposed to the Ethiopian community. I said, "We have to raise enough money that the interest will pay for an ongoing course in Ge'ez,” because without Ge'ez, there's no way we can get anybody to comprehend what is written on these literally millions of parchment manuscripts which are lying here and there in Ethiopia. In other words, the real study of Ethiopian history and society cannot take place until people can read Ge'ez.

Now, we do have colleagues in Europe who can. I mentioned Hamburg is one place. There's another center at Naples in Italy. In Rome, you can learn any language in the world that you want through the Papal educational system. This would be a first in North America.

Coming to Ethiopia, you have this very large population of people whose language, especially Amarigna and Tigrigna, is based on Ge'ez, but only the priest can read the language. What we need is, I think, to move away from church learning and make it an academic language so that not just members of the priesthood can look into the many, many, many manuscripts which are available, but the scholars can do it too. Basically it's like looking at the other side of the moon. Getting the first photographs of the other side of the moon. You know it's out there but you don't know what's there until you've actually seen it. That's my reasoning behind promoting the idea that we teach this third important Semitic language.

When the university—which has been very enthusiastic about this project by the way—decided they were going to teach it, they were going to go out and look around and see if we can find someone who knows how to teach it. It turned out that one of their own faculty members, Robert Holmstead, already knew the language. He stepped forward and said he’d like to teach it. We had that little secret right there in the department without anybody knowing about it.

That’s amazing! In terms of the course that's being offered in January, who is able to sign up for it?

It's open to the university community, so both undergraduates and graduates could take it. I imagine that we'll have some Ethiopians, because this will be the second-generation Ethiopians now who are growing up and have reached their teenage years. Their families, their parents will not know Ge'ez, unless there's a member of the priesthood somewhere there. If there's enough interest in what they've left behind, I think certainly some of the students from the Ethiopian community will want to learn the language.

On the other hand, I suspect it's going to appeal equally, if not more, to the graduate community who are interested in, as I mentioned the other Semitic languages and East Africa. Perhaps I could underline that point too. When we have African Studies programs in North America, they tend to be based upon Colonial Africa. In other words the British, the French, the Portuguese, the Italians, the Germans all had their colonial interests in Africa, to a greater or less extent. So this is what Colonial Africa was all about. The whole of Africa was divided up among these European interest groups. Now, as long as the Colonial period went on, they issued documents in the home language. A scholar who's interested in Colonial British Africa can do a lot of serious research without knowing any African language because he can go in using English. The same is true with French and the same is true with Portuguese and other languages. But, if you look at those programs, you can dig, dig, dig, and you probably will not find anybody working in Ethiopia, because it was not colonized, except for the five year period between 1936 and 1941 when the Italians were there. There's not this close European link. And again, what interferes with the research is the fact that people don't have the language. That's the key.

For our readers who are interested in learning more about what the course will go over, what advice do you have for them? What resources should they check out?

One of the most important things is the collection of Ge'ez manuscripts which are being put online by the University of Toronto. If we're looking at internet readers and they would like to see this material, that would be the site to go to.

Just again this morning, I received a message from an Ethiopian-American who is teaching at Makerere University in Uganda, and he said he would be interested in seeing this course made available online. In other words, such that people could possibly learn through online attendance. Now, that's a little premature for us but it's certainly a possibility. Therefore if your online readers showed a serious interest, it would be worth letting the University of Toronto know. Then they might invest some resources because there are lots of courses now which are available online.

For those interested in learning more about Ge'ez, check out the Gunda Gunde Project online, Professor Michael Gervers' current research project supported by the Arcadia Fund in the U.K. and the Mazgaba Seelat research website (the UserID and Password for this is "student").