On its 30th Anniversary, the Pan African Film Festival Looks Back —and Ahead

The film festival returns in person this year -- after date shifts and virtual programming -- to celebrate 3 decades of promoting African film.

Much has been said and written about how film festivals are navigating a world upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. Not enough is being said or written about how festivals specifically targeted at particular communities are continuing on. For the Pan African Film & Arts Festival (PAFF), arguably the largest international Black film festival in North America, and an important stop on the festival circuit for filmmakers from Africa and its diaspora, the pandemic meant going virtual for the 2021 edition.

To ensure that the festival’s 30th anniversary celebrations are able to go ahead with a physical component, the PAFF team decided to move this year’s event from its traditional spot on the February calendar – where it would normally be a highlight of Black history month – to a later date that begins April 19 and runs through May 1. But what would Black history month look like without PAFF’s annual display of the beauty and diversity of film and art talent from across the globe? As somewhat of a placeholder, PAFF put together a retrospective series highlighting some of the most notable and beloved films that have played the festival in the last 30 years.

This year-long series kicked off in February, in honor of Black history month, with virtual screenings of titles like Viva Riva, Of Good Report and Agents of Change, and continued in March, with a program dedicated to female filmmakers for women’s history month.

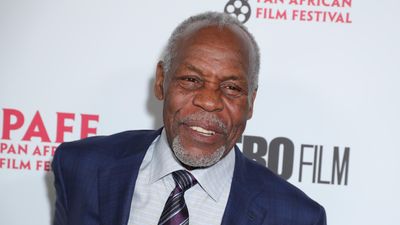

PAFF was founded in 1992 by the trio of actor and cultural activist Ayuko Babu, who also serves as the executive director, Hollywood veteran Danny Glover, and the late actress and singer Ja’Net DuBois. PAFF’s general manager and director of programming Asantewa Olatunji, who as a young lawyer was involved in the very first edition, gives OkayAfrica a brief history. She recalls: “It all started with a group of community activists. None of us was a filmmaker but we were interested in the images that were being projected of African people around the world particularly here in the United States. We had travelled quite a lot and we did not see on the big screen what we saw when we travelled around Africa, and so we decided to do something about that.”

Photo: PAFF

Pan African Film Festival co-founder Ayuko Babu with actress Alfre Woodard.

This was a very different time in Hollywood. The Blaxploitation era that was popular in the seventies was long over. Mainstream studios avoided green-lighting Black-led films claiming that such projects were not profitable and did not play well internationally. The few films that were made about African Americans were mostly concerned with Black pathology - crime, hustlers, pimps, drugs, that sort of thing. The rare African film that made it to screening rooms in the United States was likely to be invested in exotic images of poverty and desperation.

PAFF’s objective was to bring films to the United States that showed a realistic and honest view of Africa and African people around the world. It has since grown to be a cultural staple, even serving as an Oscar-qualifying run for the narrative shorts category. For Glover, who is the celebrity ambassador for the 30th anniversary, this year’s event is also a chance to reflect. “The Pan African Film Festival is a cultural icon that has grown over the past 30 years into the largest Black film festival in the U.S., and I’m proud of any role I played in making that happen,” he said, in a recent statement.

The first edition of PAFF, held in the now-defunct Laemmle Sunset 5 theater in South Los Angeles, was a hit, with celebrities like Whoopi Goldberg and Rosalind Cash lending their star power. First lady of Burkina Faso Chantal Compaoré, a big supporter of film in her day, was a special guest. Med Hondo’s seminal epic Sarraounia opened the festival, and titles like the Sundance-winning Chameleon Street and the Tsitsi Dangarembga-penned drama Neria screened for audiences across the next seven days. Olatunji recalls the excitement of the early days: “When we first started there were very few films of African origin that played in the US, and when they did play, it was mostly in colleges and university towns and cultural institutions. We proved that people are interested in these films.”

PAFF sought to improve, through film and art, relations between Africa and her considerable diaspora. This relationship between Black cultures, long interrupted by decades of slavery and colonialism, has, in the wake of the internet and voluntary migration, deepened in recent times. But PAFF was there long before this cultural explosion. Olatunji breaks it down further: “PAFF is — and has always been — about celebrating who we are together, and at the same time attempting to understand our differences. We come together as a proud, intelligent, proactive group of people who like everybody else have ideas and want to contribute.”

Photo: PAFF

Pan African Film Festival co-founder Ayuko Babu with actor Idris Elba at the 2020 edition of the festival.

Desmond Ovbiagele, the filmmaker behind the terrorist drama, The Milkmaid, Nigeria’s first ever submission in the foreign language category at the Oscars, has screened two of his films at PAFF. He tells OkayAfrica about his experience with the festival, “I am impressed by the enthusiasm of the organizers not just for [African-] American films but also films coming from the continent itself. The way the festival has positioned itself as a bridge connecting African filmmakers with the African-American community has given access to our films and helped cement common bonds.”

An American filmmaker who spoke to OkayAfrica under the condition of anonymity explains that while she would still submit future projects to the festival because “it is an important festival, and everyone goes there,” she was not impressed by the logistics as a guest of the festival screening her film. In her recollection, “There weren’t shuttles gathering people from one place to the next. It felt disorganized like it was their first time, and this is a fest that has been around for 20-something years. I get that there is not enough funding but as one of the most prestigious Black film festivals in the United States, I think they can do better.” Fest organizers have yet to respond to a request for comment about this.

One of the ways that PAFF connects with its host community is by providing representation through the concrete images of Black life that appear on screen, as well as the celebration of the people who make them. The festival manages this through red carpets, panels and Q&As, and everyone from Denzel Washington to Ava DuVernay has stopped by. Olatunji explains further: “One of the things that we have been able to do, in whatever small level, is to give a foundation to our audiences of what Black life is like. We introduced this very real, authentic representation of the kind of people that we all are, and we all know. We promoted those films, the images and those people who made them. And for the last 30 years.”

Ovbiagele who screened The Milkmaid in February as part of the Black History Month retrospective series couldn’t agree more. “Along the years, PAFF has been quite clear about its objectives as the largest Black film fest in America,” he says. “Long may it continue.”

- FESPACO 2015: Africa's Largest Film Festival In 15 Photos ... ›

- Pan African Film Festival Set to Screen Black Panther Documentary ... ›