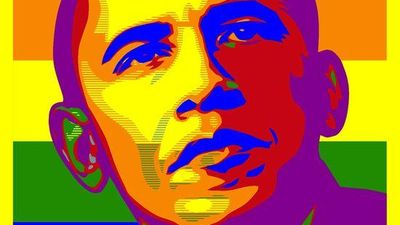

Should Obama "Speak Out" About Gay Rights in Africa?

As LGBT activists call for Obama to speak out against anti-gay laws in Africa, we discuss the potential fallouts of such diplomatic action

* President Obama meets with President Sall (Senegal), President Banda (Malawi) President Koroma (Sierra Leone), PM Neves (Cape Verde) Photo Credit: Pete Souza, March 2013

Soon President Barack Obama will set out on his visit to the continent that this week, Rick Ross (fondly but incorrectly) referred to as 'the beautiful country of Africa.' In advance of his visits to South Africa, Tanzania and Senegal, column inches continue to swell with analysis and advice for the President (as well as questions about why Kenya has been left out in the cold). Among them are calls from African and Western LGBT groups, for Obama to condemn African governments' legislation against LGBT Africans. Although for decades, anti-sodomy laws remained in African nations' statutes as leftovers from the colonial era, the past five years has seen a marked shift towards the criminalization of homosexuality. Claiming that homosexuality is "un-African" or "a lifestyle choice," Burundi and South Sudan have created new laws to outlaw it, while people "accused of being gay" have been brought to trial in Cameroon, Malawi, and Uganda. Meanwhile, Nigeria and Libera have proposed harsher sentencing for LGBT people and their allies. Last week, Amnesty Internationalwarned that homophobia has risen to "dangerous" levels across the continent prompting U.S. LGBT activist Richard Socarides to ask that Obama "speak out about the principles we value in our democracy and how we would hope that others follow it". Given the Supreme Court decision to strike down the Defense of Marriage act and Prop8, it's likely that if he does make a statement on gay rights, Obama will use these domestic victories to create "teachable moments." A few of us got together to discuss the complexities of U.S. diplomatic intervention, and its potential implications in the debate over gay rights in Africa.

AYANA: My opinion is a conflicted one. I think that it's a dangerous liberal move to insist that Obama speak out when the naming of LGBT interests (in the US called "the gay agenda") is so dismissive of actual individuals on the LGBTQ spectrum, in America or anywhere else. Obama could speak out against the new homophobic laws in Nigeria, but should also condemn laws in the US that have led to an increase in LGBTQ homeless youth, to increased incarceration of queer individuals, and laws/customs that shatter the support provided by chosen family structures, in favour of the insistence of state-by-state approved, mainstream gay marriages which limit federal and local support in healthcare, education, and employment. Speaking out would be nothing short of hypocritical, paternalistic and pinkwashing if he didn't address America's problems as on a spectrum of its own that is also flawed and a work in progress (to put it more than optimistically).

MONA: Like Ayana, I feel conflicted about the urge for Obama to "speak out" on LGBTI rights during his African tour. It has the potential to spark constructive debate, but it also the raises the issue of whether or not this is a moment of neo-colonialism. Although Obama isn't visiting Malawi, I'd like to speak to the ripple effects that his trip could have on my home country. I think that Obama's voice has the potential to liberate the minds of Malawians. Obama holds a lot of cultural capital in Malawi - from Obamas that are donuts sold on the streets, to zitenje with his face printed on it - and I imagine if he raises concerns about anti-gay legislation in Malawi, it could at the very least result in much-needed vibrant media debate. At the moment, there is a polarised split in the public space between D.D.Phiri, an archaic historian, who is outspokenly homophobic, and Udulence Mwakusungula and Gift Trapence who are supporters of LGBTI rights and have a weekly column in The Nation titled Sexual Minority Forum. We need more diverse voices supportive of LGBTI rights in the public sphere; Obama could be a respected voice that rustles the negative assumptions of people who are resistant to change.

DERICA: But don't we already know how such a statement goes? Obama will use a perceived U.S. triumph over homophobia as license to talk down to African nations and leaders. We saw this same power-dynamic inform his address to the Kenyan electorate and the decision to meet with a group of African heads of state. I'd be more interested in a statement from Obama addressing U.S. Christian evangelicals who exacerbate existing homophobia and influence politics in various parts of the continent. That said, Mona, I hear you about Obama's influence, and agree that a shift in attitudes is a potential, and desirable, outcome. But I do think that for all the zitenje and donuts, when Obama starts talking about LGBTQ rights he stops being considered an 'African son' and becomes an American. Plus, I don't think external pressure works that well. We’ve already seen African governments hijack pan-African rhetoric to frame their criminalization of homosexuality as a way of 'sticking it to the West'. Of course it's despicable that leaders should so cynically adopt that language of African unity and resistance in order to score political points, but I think a statement from Obama would only deepen the current discursive rut.

MONA: The approach that Obama's administration has taken has been perceived as one that reeks of cultural imperialism. In December 2011, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama stated that American aid allocation should be influenced by minority rights of recipient countries. In November 2012, Joyce Banda suspended anti-gay laws, which was a welcome move in terms of pumping donor money into the country and promoting human rights, but it would have been a more effective change in the country's history if it had been a ground-up movement rather than top-down decision. This progress could be seen as a result of foreign interference rather than local necessity. In addition, any loud and incessent voices coming from outside Africa have the potential to overpower internal voices, thereby disrupting local ownership of the process. While there is power in the pro-gay statements that come from Obama's adminstration, it could be more powerful to hear these sentiments from Africans.