A Letter to Moses Sumney, From a Romantic to an Aromantic

Dear Moses, your new album 'Aromanticism' wants us to stand still and embrace the absence of romance, instead of falling in love—making it ok to be alone.

Dear Moses,

The other day, when someone dear to me asked what I have been listening to lately, all I could name were love albums.

Daniel Caesar’s Freudian has been my audio medicine. It's soaked in such heavy waters of infatuation that I find myself wringing out every song like cold, wet laundry that will never dry. D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar has been soothing for me as well—although it came out when I was only 5 years old, 2 decades later it remains sonically relevant and endearing. And then there’s Sampha, the infectious crooner who loves nothing more but to wear his heart on his sleeve.

I say this to convey that I am one of those humans who dwells in enamor, who wants to understand and experience multifaceted emotions and relationships. I’m fascinated about love and the many shapes it can assume. Also, sex. And honesty, self reflection and emotional intelligence. These are the lessons we don’t learn in school, the courses that only life can teach us, if we choose to pay attention. I am an avid learner.

My interest in romance sounds cliché: I'm all too aware of how society and culture teach women to be consumed by love. To feel it in our every step, to crave it in our bones when a lover leaves, and sadly, when they sit right beside us. To base our very existence on love, the search for it and the expression of it, as if it is what our bodies and minds are made for. And worse—to feel incomplete or disappointed if it doesn't arrive to us in time, in our vision or arrive at all.

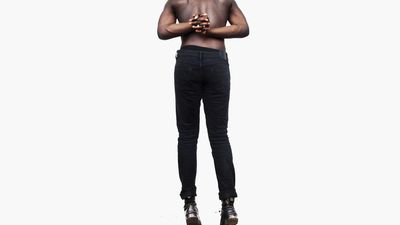

Yet, the standards of love and romance apply to men too. You, a graceful black man with roots in Ghana and footprints in Cali, have written your own musical narrative that directly rejects what society says about love and relationships.

Black men who sing are usually expected to sing about a woman they want, or lost and want back. You do neither. I know nothing about your love life, who's laid in your sheets, who you wish would lay in your sheets. Who broke your heart, whose heart you broke. I just know you're aromantic: a person who can feel love, desire and other tender feelings, but doesn’t necessarily want, or sees the importance of, being in a romantic relationship.

Your music illustrates the alluring yet ambiguous nature of human connection, loneliness and feeling, like in “Pleas,” one of my favorites on your new album, Aromanticism. You sing: “Can you talk in monochrome?” aware that language and romance is so much more colorful than this, but you challenge the person to speak in your tongue. Then later, “I need to know if you hear my pleas...do you wanna spend the night? Pleas,” because, physical desire is as simple as monochronicity: your lover shares one color, and you, another that compliments it. Together, you create a brand new hue, originated from the same shade of momentary wanting.

With Aromanticism, you continue this journey of contemplation on desire, loneliness and the overbearing ways society tells us to commit and practice romantic relationships. For my ears, it is a refreshing transition from the songs of longing, lust and sensuality that I drown myself in. It's like floating, taking a break from swimming: I lift my head up above water, measure the distance from water to shore. I reaffirm that romance is not necessity, but rather, a choice or a happening. And for some, not an option at all.

What initially intrigued me about Aromanticism is that most of the tracks follow the formula of a love song: instrumentally, they're composed of sounds and rhythms that inspire daydreaming and tenderness—misty harps, rugged bass, twinkling piano. Matched with your voice, which is both achingly feathery and lustily robust, it is easy to get carried away before one listens to your lyrics and realizes you are in fact urging us to do the opposite. You want us to stand still, to confront the absence of romance, instead of falling in love, the natural response we’ve been conditioned to do.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=xDWFX7cO9co

In “Don’t Bother Calling,” you let someone down gently. You’ll call them when you’re ready or if you want to. “You’re made of solid, I’m made of liquid...trust, I am the son of the sea,” you sing, referring to the free flowing quality of your form, the way water moves on its own, even if it is contained. As a water sign, I understand this too well: I sway in my own direction, I contain emotions so fierce that some can call it a tidal wave. When met with a solid, fixed force, we push against what will not budge, aware that we, conversely, cannot stay still.

There’s a difference between rejection and inability or uninterest. Rejection feels personal; it is about us but not about us, all at once. But to not want something, or feel the need for it, has nothing to do with the other person. “Quarrel” insists that the person doesn’t confuse the connection shared as an actual relationship. It's so persistent that it's compelling: sometimes when someone says they don’t want it, it makes you want it even more. It’s unfair to both parties, but also natural, like a moth to a flame burned by the fire.

Perhaps that’s why, for now, I'm most drawn to “Make Out in My Car”—and, coincidently, it's the only song that explicitly requests touch and sensuality, even if there are boundaries set in place. “I’m not tryna go to bed with you, I just wanna make out in my car.” I’ll put this song on repeat the next time I’m making out with a guy but I don’t want to make love to him.

Yet, you address the loneliness of being left behind by a society that values matrimony over self sufficiency. “All my old lovers have found others...I was lost in the rapture,” you croon in “Indulge Me,” reminding me of how God asked Noah to take male and female pairs of animals on his boat before the flood. Where do loners go, in a world where lovers float into the clouds?

The lulling, fantastical company of Aromanticism suggests that the absence of commitment doesn’t have to be depressing or pitiful—it can be as magical, trying and fulfilling as romantic love. Far too often, our culture devalues singledom as if it's a dysfunction. Musically, artists rarely explore the act of being alone as a cerebral state of invigoration, questioning, acceptance and empowerment, except for revelationary break-up albums—but even then, the absence of relationships is still centralized.

Sustaining relationships is just as difficult as deciding to be in one. Maybe this is what our culture doesn’t comprehend: that monogamy is difficult for some, and alternate relationships, or non-relationships, relieves us of the expectations of loving one spirit forever. The incredible honesty of Aromanticism not only encourages us to understand your identity, and that of others who share your perceptions, but also to open our minds to the possibilities of other ways of loving, exploring our sexualities and connecting.

“Am I vital, if my heart is idle?” you beg in “Doomed.” You’re aware that we symbolize the heart as a machine that pumps both blood and yearning through our veins, as if passion is as vital to our existence as plasma. But what if the silence of the heart is just as functional, just as heavenly? We spend so long looking for our missing piece that we forget we are already whole, inherently complete.