When Malick Sidibé’s Photographs Danced Before Me

The Malian photographer helped shape an African worldview and created a lexicon of black identity.

My interest in the politics and aesthetics of photography started from an unlikely source: Dambudzo Marechera, the enfant terrible of African literature. In his seminal text The House of Hunger, a coming of age novella set in the 60s and 70s, he writes about Solomon, a township photographer who could obliterate 'the squalor of reality' with his photographs. His customers, who have little hope of ever leaving the township can only realize their dreams of escape through the illusions he creates:

Photographs of Africans in European wigs... Africans who pierce the focusing lens with a gaze of paranoia. The background of each photo is the same: waves breaking upon a virgin beach and a lone eagle swiveling like glass fracturing light towards the potent spaces of the universe. A cruel yearning that

can only be realized in crude photography.

The residents of Marechera's house of hunger were growing up in the era of Malick Sidibé's early photography. At the time, they were bombarded with images from colonial media institutions. These constructions of blackness were proverbial masks that, writes Laura Taitz in Emerging Perspectives on Dambudzo Marechera "served to hamper any attempt at self-definition or self-representation." The masks embody the contradictions of colonized identities and the politics of representation, subjects Marechera obsessively grappled with in his subsequent works, Black Sunlight and The Black Insider.

Sidibé is the antithesis of Solomon. He set out to change the idea of black beauty and fashion through his street photography and studio portraits instead of imposing or maintaining the prevailing photographic models based on Western aesthetics.

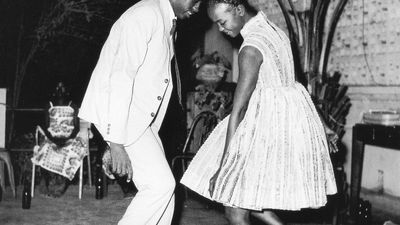

Surprise Party, 1964 By Malick Sidibé

The first image of Malick Sidibé I encountered was the portrait of a young couple dancing at a Christmas party. It is one of the most iconic images from his oeuvre that spans a wide spectrum. The pose here is unrehearsed. It is graceful and dynamic and encapsulates the hallmark of Sidibé's photography that captured the energy and hope of a generation of young black Africans living in a period of political and social transition.

His early photography affirms his participation in the decolonization of the 1960s, and in shaping the new look of young black and proud Africans who were consciously stylish and au courant. There is something rebellious and doggedly determined in their moves and gazes. By photographing them in the manner in which they wanted to be seen, Sidibé too was insisting on their right of being.

Looking at his photographs today, it is easy to see how productive they were in shaping the African worldview and creating a lexicon of black identity. Sidibé never stopped documenting youth culture and style in Mali. His photography journey began with youths dancing their way out of their colonial past into an era of freedom, expression and fashion.

The import of Sidibé's contribution to the African sensibility and image is huge. His work is understated and yet sophisticated in its detail, especially the interaction of space, movement and subject. He was the first African and the first photographer to win the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2007 Venice Biennale that was themed, “Think with the Senses Feel with the Mind." His place in the pantheon of photography greats is assured.

- 100 Women: Malin Fezehai Is the Renowned Photographer Helping ... ›

- Spotlight: Artist, Ngadi Smart, Captures Black Sensuality, Sexuality ... ›

- Photos: #AfricanVintageLove Is a Celebration of the Couples In Our ... ›

- Black Social Photography in South Africa: Before & After - OkayAfrica ›

- Remembering Malick Sidibé - OkayAfrica ›

- Spotlight: Meet the South African Street Photographer Capturing Photos of Black Life in the Johannesburg CBD - Okayplayer ›