Keeping Ancient Rock Art Alive Across Africa

There are an estimated one million ancient rock art sites on the African continent. These people want to document all of them.

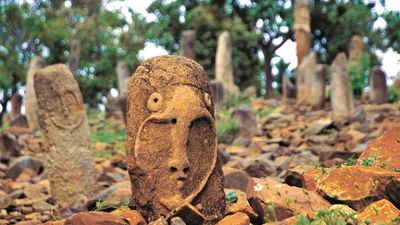

By combining finely ground red rock with animal fat and methodically smearing it on rocks using a single feather or fingers, a potent kind of storytelling emerged. Its imprint has lasted generations.

Thousands of years ago rock art was a fashionable ritual. Not today. With the ancestral painters long gone and the societies that painted now history, finding the moral and material support to preserve these artifacts is tough. Preserving these frameless stone paintings on cave walls and open air hilltops is the new struggle.

Rock art researchers across Africa spent many years trying to bring the subject into the public consciousness, to no avail. Trust for African Rock Art (TARA), based in Nairobi, Kenya, was created 20 years ago to document, conserve and create awareness around the significance of this pan-African heritage and its endangered state.

According to David Coulson, founder of TARA, this means traveling to rock art sites, documenting them using various technologies and working with custodian communities wherever possible and in partnership with national bodies to both create awareness, and conserve sites.

“Conservation for us means creating a database of this art; and where possible establishing income generating community-owned tourism projects," says Coulson.

The Price of Rock Art

African rock art is heritage in the sense that it is an accumulation of things expressed in images—histories, memories, symbols, and mythological and ritual records—passed down to us from generations before, says Wangũi Kamonji, TARA communications co-ordinator.

“Rock art is often the only existing record of thousands of years of African history and culture,” she tells Okayafrica.

On another level it is art history: some of the earliest artistic expressions of humankind. It’s also the beginning of visual communication, and a form that has survived for thousands of years, she adds.

Kamonji sees in rock art archaeological remains—prehistoric art enables researchers to build pictures of past lives, belief systems and social concerns, ways of representation, and what was held to be of importance.

“African rock art is beautiful. Personally it gives me a sense of pride to see the art and think of the ingenuity and intelligence that went into it: creating paints, preparing surfaces, making brushes and other tools, drawing, etching, carving, painting, the sense of perspective and of movement, long before artists in other continents had developed those skills,” she says.

Locating Rock Art

There are close to a thousand locations on TARA’s website, each with multiple images, in some cases hundreds. TARA estimates that there are over a million sites for the whole of Africa and that almost every country in Africa has rock art.

“When we started work 20 years ago in Kenya the museums knew of about 5 sites while today we have pushed that number to nearly 100,” says Coulson.

The Sahara desert alone is believed to have at least a quarter of a million sites some of which have literally thousands of images, he adds.

A few years ago Coulson was asked by TARA’s principal donor if they had documented all the rock art there was in Africa.

“I was amazed at the question, I reminded her that, the Sahara desert alone is larger than the USA and has no roads. So the task is immense and we must have help to document as much of Africa's past as we can before it is lost forever.”

The Threat Is Real

African rock art is often threatened. In Europe, paintings are usually found in deep protective caves while in Africa it often in the open or in shallow rock shelters, making it more vulnerable, says Kamonji.

“Primary threats are vandalism—graffiti, destruction, theft—by people who either don’t know the worth of prehistoric art, who have something against it, or who stand to profit from selling broken off pieces of art in the black market,” she says.

Other threats are unintended or known consequences of sites- the disturbance caused by mining, and projects such as road building, may cause rocks with art on them to be damaged and destroyed. Heat and rain also cause weathering and degradation of the rocks bearing art.

In some places, however, the situation is less bleak.

In Botswana, Angola and Morocco, to name just a few places, communities, or government authorities have realized the value of protecting the art. Similarly, TARA has supported community projects in Niger, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

Coulson says these projects were developed as a means of helping communities living around rock art to benefit economically from the rock art, as a way to strengthen their role as today's custodians of the art.

“Often the communities now living near the sites are not descended from the original artists yet they have long ago inherited the heritage and sometimes usage of the sites and absorbed it into their own worldview and belief systems,” he says.

In South Africa, rock art is better known and a part of the national consciousness. It is incorporated into state symbols such as money, the coat of arms; and also into the university curricula. Research at places like the Rock Art Research Institute based at Johannesburg's Witwatersrand University lends intellectual value, and interest in rock art for the Southern African rock art.

The State of Africa’s Rock Art

Even so, rock art is not getting the attention it deserves on the continent. Kamonji says very few people know about rock art in Africa.

“Rock art is not included in schools’ curricula even where archaeology is taught as a unit in history. Many history books in schools across Africa start with the colonial period even though Africa's history is incredibly rich and goes back long before most European history,” Coulson adds.

Rock art is often located in remote areas: the middle of the Sahara, the deserts of Northern Kenya, the Lope-Okanda National Park in Gabon and in the Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa and Lesotho.

Knowing where to find sites and to get to these sites are two different things. TARA has been bridging this mismatch by taking photographs that it makes accessible to researchers and interested people internationally. And by providing guided safaris to rock art sites.

“We open windows onto these vanished worlds. But to actually visit these sites in the flesh is the most special way to really understand appreciate their significance, because rock art was sometimes made for spiritual and mythological reasons and the sites are therefore sacred places,” says Kamonji.

While in France and Spain, a single cave might contain thousands of paintings, African rock art is often spread out.

“In Africa, there might be an outcrop here, a small shelter there, a shallow cave further on in a more spread out way, each with its own special and unique images. More conducive to a hike, and perhaps more of an accumulative experience,” she says.

“You can’t pick up rock art and take it to a museum… well you can, but that would change the art. Removing it from its original setting within a particular landscape and context—a context that might have provided some inspiration for the artist—would no longer be the same. Perhaps the fact that it’s out in the open, and one can’t quite own it makes it difficult for people interested in heritage conservation to care about and understand it.”

Kamonji says TARA is the only organization committed to rock art documentation and conservation continent-wide but as small and underfunded as hey are, there’s many things they would love to do but don’t have the capacity to start.

“Most important of all is the need to include rock art in school curricula across the continent as soon as possible because rock art is our record of the earliest history and a massive statement concerning Africa's rich and often magnificent past,” Coulson says.

TARA has partnered with the British Museum to provide a copy of its database comprising more than 25,000 images which is being uploaded to a dedicated site. These will be available open access to anyone with an internet connection and device. Social media is also a fast growing way to bring rock art to the younger generations.

More Work

TARA plans to record contemporary use of ancient rock art sites in southern and East Africa in order to understand more about past beliefs and about possible connections between existing traditional communities and past rock art communities.

In the Sahara in northern Chad an expedition to record remarkable and ancient life size engravings of decorated women using advanced photogrammetry techniques is planned.

According to Coulson this technology will allow the creation of life-sized, 3D replicas of these amazing figures for exhibition in major museums globally.

“We believe that documentation is a vital form of rock art conservation in that in times to come the majority of this heritage must eventually disappear but if we have documented it will still be, digitally, there for our children’s children to enjoy and study."

Undying Tradition

The desire to keep the old heritage alive has not stopped new ones being created.

In Bandiagara, Mali, Dogon community members paint and repaint art on cliffs surrounding the community regularly during specific important rituals.

In Kenya, Maasai warriors also continue a finger-painting tradition that is connected to meat eating and initiation feasts.

Coulson says in most other parts of the continent people do not make rock art anymore.

In the Sahara, the people who lived there and made engravings and paintings of crocodile, giraffe and elephant and a host of other animals and people, moved away or died out when the formerly green and lush Sahara dried out about 4000 years ago.

In Eastern Africa, a hunter gatherer community of artists known for their geometric art vanished long ago following the disappearance of the tropical forest, once part of the Central African Rain Forest.

In Southern Africa, a lot of the art was made by San communities. When new Bantu communities moved into formerly San occupied areas, such as the hills and mountains in Zimbabwe, South Africa and Mozambique, they came into conflict and the San were either absorbed into these new communities, killed off, or moved away. Both black and white pastoralists and farmers effectively exterminated the vast majority of San hunter gatherers during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

“After the surviving San became refugees they lost their painting tradition,” he says.