Théo Is Not the First and Won't Be the Last Face of France’s Institutional Racism

An op-ed in the wake of continued protests in Paris after a Théo, a 22-year-old black man, was brutally attacked by police.

"Sambo, it's a pretty suitable term."

This is confirmed by a disconcerting assertion by Luc Poignant, union representative of the French police, live on public television on Thursday, February 9. “Sambo” is also a hostile, racist insult that still resonates in the ears of a young man with no history. A week before this declaration by a union leader in Aulnay-sous-Bois, a poor suburban city of Paris, the life of the one who is now nationally known by the name of Théo topples into a horrible nightmare.

According to his testimony, Théo sees policemen conducting an identity check on his comrades and intervenes, when one of the officers administers "a big slap" to one of the youth. What ensues plunges the young man into a whirlwind of horrors: after brutally inserting a truncheon into his rectum, officers sprinkle him with tear gas, handcuff him and administer a series of beatings: “They struck me again, They put me handcuffs, blows of truncheons in the private parts. They spat on me, they called me nigga, sambo, bitch," he recalls, recalling the context in which many policemen use degrading rhetoric that was considered “suitable" for the profession by a prominent union representative.

Instead of driving Théo to the hospital, while he suffocates, the police transport him to the police station. Remember, Théo did not commit any offense. Théo’s ordeal will end when an agent, worried about his condition, ends up calling the SAMU (System of Emergency Medical Assistance) who takes him to the hospital. A doctor discovers a longitudinal wound of the anal canal that is about 10 centimeters and a section of the sphincteric muscle. He determines that Théo is totally incapable of working for 60 days.

The four policemen are charged. Three of them for “voluntary violence” and the fourth for “rape.” They all go home free. Such overwhelming events should have been unequivocally condemned, yet very quickly a legal source interrogated by the AFP (Agence France-Presse) during the preliminary investigation, affirms the improbable: the trousers would have "slipped alone." A few days later, the General Inspectorate of the National Police forwarded its reports to the investigating judge in charge of the arrest case.

While these first observations display a "serious and real accident," they deny the existence of a "deliberate rape."

At the same time, the lawyer of the police officer charged for rape qualifies the act of his client as "involuntary" despite French law adamantly describing rape as "any act of sexual penetration of any kind committed against the person concerned by violence, coercion, threat or surprise." How can we reasonably deny this sexual aggression and affirm its "accidental" character?

It is important to specify, Théo is a young black man. The French media tends not to emphasize this. He is not the first in France to suffer the excessive force of those meant to uphold order. Unfortunately, the "Théo affair" is in the context of endemic institutional violence directed against minorities on a recurring basis. Identity controls, mostly unjustified, are often the starting point for sudden brutal escalations.

According to the latest report by the Human Rights Defender, the administrative authority in charge of combating discrimination, 80 percent of young men perceived as Arab or black say they have been checked (compared to 16 percent for the rest of the respondents). They are 20 times more likely to be checked than others. In the ACAT’s (Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture) investigation into the use of force by law enforcement officials in France, it describes "members of visible minorities" as "a significant proportion of victims...particularly deaths."

If we speak about Théo today, it is because despite his misfortune, he survived this violent ordeal.

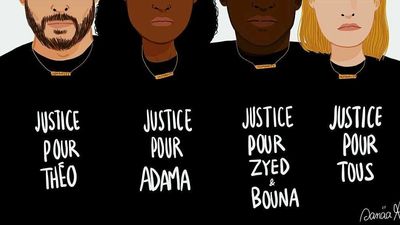

Today, he can testify regarding this brutality, that which, each year, too many anonymous individuals succumb to in the most deafening media silence. A few months before Théo, the Adama Traoré affair shook France’s public opinion. While the eyes of the world are focused on the United States, where two black men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile are dead, killed by policemen; the death of a black Frenchman in troubling circumstances does not seem to arouse the same emotion. On July 19, in Beaumont sur Oise, a city on the outskirts of Paris, Traoré was arrested while fleeing an armed police officer for fear of being arrested because he did not have his identity papers on him. A few hours later, he died from asphyxia. Traoré was a black man and his name lengthens the already exhaustingly long list of frenchmen dead at the hands of police force.

In France, police officers do not use firearms as often as their American counterparts. Here, police violence is expressed in other, less "spectacular" forms. It commonly comes in the form of beatings and humiliation. Deaths are not often linked to bullets but to the obstruction of an individual’s airways. Thus, in 2007, Lamine Dieng died asphyxiated in a police van, in 2008 Hakim Ajimi lost his life, suffocated by the chest compression and the strangulation practiced by two policemen. In 2015, Amadou Koumé died from suffocation despite being stopped in a bar. Hocine Bouras, Amine Bentounsi, Abdoulaye Camara, Zyed Benna, Bouna Traoré and hundreds of others—each year the names of the people who have disappeared killed by the police succeed one another and resemble each other strangely in their Arabic and African consonances. According to Amnesty International, 15 people die at the hands of law enforcement every year.

These disappearances hidden behind the walls of police stations or in the secrecy of vans are less likely to be captured in the form of videos or broadcasts like they are in the United States to alert international opinion. Théo had the intelligence to approach a surveillance camera placed in the street. This is the first time that such overwhelming evidence has been circulating via social networks. What has always been known to the inhabitants of the working-class neighborhoods is now visible to the majority and incites international indignation.

After several nights of agitation and the expression of the widespread anger, President François Hollande went to Théo’s bedside. The symbol was strong but it significantly contradicted the president's inaction against police violence. During the presidential campaign of 2012, he committed to fight against the control law enforcement imposes on the people. It was then a question of putting in place an order requiring police officers to leave a written record for each control and to motivate each one of them. This proposal never came into being.

Théo was set up as an exemplary figure. I do not doubt his moral qualities, but respectability must not be the obligatory corollary of dignity. No one deserves such treatment, no matter what misdemeanor they have committed. Théo survived and will no doubt suffer for a long time from the physical and psychological damage caused by the barbaric treatment that was inflicted upon him. Today, his name bears the symbolic burden of systemic violence that has taken too many lives and his face is now that of the post-colonial racism that sullies French institutions.

Rokhaya Diallo is a French journalist, writer, award-winning filmmaker and social justice activist. She's also the host of two shows on BET France—BET Buzz and BET Docu. To keep up with Rokhaya, check out her blog, RokMyWorld and her website.

- Black Lives Matter ›

- From 'Star Wars' to the War on Racism: John Boyega's Speech at a ... ›

- Interview with Assa Traoré, Leader of 'Justice for Adama' - OkayAfrica ›

- In the Movement for Black Lives, Do African Lives Matter? - OkayAfrica ›

- The Police Are Cool, Totally Kidding They Are the Worst - OkayAfrica ›