5 Extraordinary Artworks at the Joburg Art Fair

Artists and gallerists take us inside some of the best works at the 2016 Joburg Art Fair.

The FNB Joburg Art Fair wrapped up yesterday at the Sandton Convention Centre. South Africa’s largest contemporary African art event, the ninth edition of the fair ran 90 exhibitions deep, with a particular focus on East Africa.

Ethiopian photographer Aida Muluneh was without a doubt the star of this year’s fair. If you’ve been around Jozi in recent weeks, it’s very likely you’ve come across her mind-blowing body-paint portraits. Muluneh, whose Addis Foto Fest showcased the stunning photographs of Kenyan "Jua Kali" artist Tahir Karmali and recent Recontres d’Arles 2016 Discovery Award winner, Sarah Waiswa, had a breathtaking solo booth presented by David Krut Projects.

Also representing East Africa, Wangechi Mutu was this year’s “Featured Artist.” The Kenyan-born Africa’s Out! founder brought two works with her: a sculptural piece, Sleeping Serpent II (2016), and an allegorical animated short film, The End of eating Everything (2013).

Nairobi’s Nest Collective and their founder, Jim Chuchu, also left a splash over the weekend in Joburg (as well as Toronto). Teaming up with the Goethe-Institut, they presented a film, Black Fantasia, and They Sent You, an anthology of short photo-comic vignettes set in an imaginary future Nairobi.

Of course, these were just a few highlights from one of the year’s biggest art events on the Continent. We caught up with a handful of artists and gallerists to walk us through five of the most extraordinary artworks on view last week in Sandton.

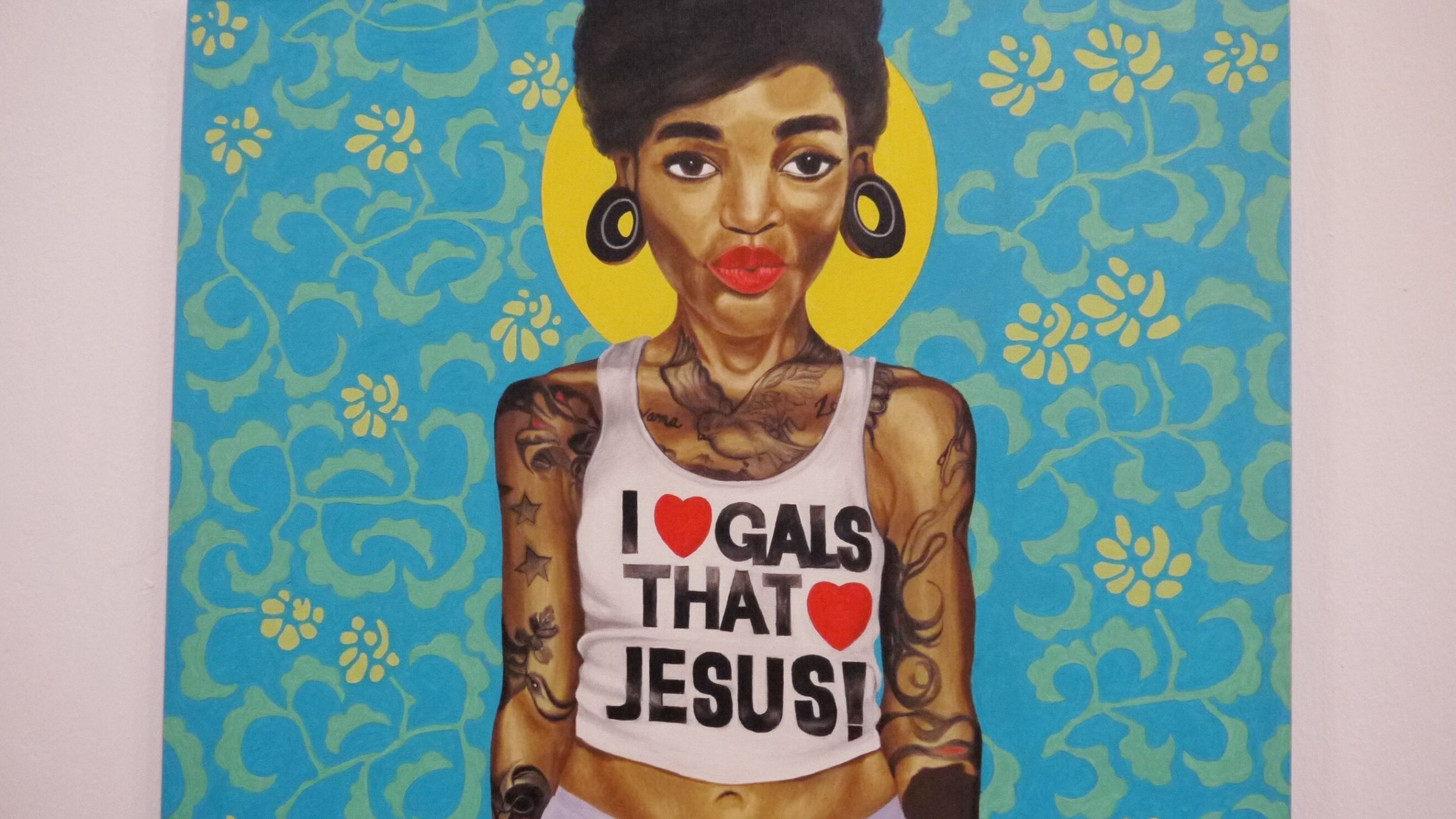

Ange Sita Swana, Gender Bender, 2016

Country: Rwanda (born); DRC (raised)

Exhibitor: Kampala Art Auction, Uganda

“It’s showing a woman standing, her upper body naked, and wearing shorts. The exhibition [Eroticism and Intimacy] explores sexualities, intimacies and the poetics of the body, and also brings to conversation the stigmatisation and criminalisation of women and queer bodies. This painting [is of] a transgender woman. She stands tall, confident, and is not afraid of her body and who she is. She stands with poise and pride and grace. And kind of brings us to think about how her body should be respected. She’s just being, she should not be criminalised or segregated because of her sexuality.”

– Violet Nantume, Kampala Art Auction

Maurice Mbikayi, Mulami Mushidimuka (Modern Shepard), 2016

Country: DRC (born); South Africa (based)

Exhibitor: Gallery MOMO, South Africa

“He’s looking at the influence of technology in our lives, and how a lot of us have just become sheep to this new system, and the economy that comes with this new digital age that we’re living in. A lot of us never really question what is behind the screen and who is driving all of that. We just follow, we do transactions online. But also the deeper story behind it is that Maurice is from the Congo, so he also explores how Africa is being used as a dumping ground for technology that is no longer of use to the West, and hence he uses the old computer keys. Coltan is mined in the Congo and gets used for a lot of our technology––cell phones, iPhones, computers––but when it’s no longer valid, it gets dumped back into Africa. A lot goes into mining all of those things; there’s issues like child labour and the political environment around it. In this piece, Maurice brings all of that into context with the conversation between the sheep and the ‘new dandy,’ or the economical power behind the technology.”

– Odysseus Shirindza, Operations Manager, Gallery MOMO

Paul Ndema, Girls That Love Jesus, 2015

Country: Uganda

Exhibitor: Circle Art Agency, Kenya

“He’s fascinated by the hypocrisy in contemporary society, particularly issues of religion and the control Christianity has over so many people. Everything he does is very satirical. I think for a while his work has been about religion, we’ve had a whole series of different paintings that are all about corruption in church, or naughty priests or the power of the church.”

– Danda Jaroljmek, Director, Circle Art Agency

Dennis Muraguri, Matatu Dots, 2016

Country: Kenya

Exhibitor: Circle Art Agency, Kenya

“Dennis is a Kenyan artist. He was born in Naivasha, but he grew up in Nairobi. For him a very important aspect of urban contemporary Kenya is the matatu, the mini bus. He’s really obsessed with them. And the more pimped out they are the better. Some of them are really incredible––they’re kitted out in velvet with huge video screens and music, and they’re painted all over with different slogans and imagery. For him it was his inspiration growing up. There’s little visibility for art in Kenya, especially when Dennis was growing up. So for him, his artistic inspiration came from the decorative vehicles. They’re completely lawless, and you either love them or you hate them, but you can’t really ignore them.”

– Danda Jaroljmek, Director, Circle Art Agency

Chikonzero Chazunguza, Seuswa / Akin to Grass, 2016

Country: Zimbabwe

Exhibitor: National Gallery of Zimbabwe

“It’s based on the archival images that I’m now using as my point of departure in my artwork, where I go into archives and I pick out pictures which I then turn into the message I may want to convey. But also kind of erasing the time in which they were taken, and living out that which is positive, and that which is relevant today. The main idea being that when the camera met with the African, it was a time of oppression or submission or imprisonment; my idea is to change those photographs as well, to make them a bit more positive, to kind of bring in some healing.

This photograph [I found] in Namibia when I was doing research in the archives of a Herero family or village. It’s about nine people who are standing, looking at the camera. And they’re looking so desperate, so worn out; even their ribs are showing. It’s an image that’s going to be there forever. This was a time when the Herero people’s space was under siege. So I take this image and I take off the bodies; the body for me in those images is what records time and the location. So I take off the location, I take off the time, and I take off the body and leave the heads and the limbs, but take off the body as though they’ll be dressed in white, kind of making them angels. And then I repeat this picture, because when I look at Namibia now, the Hereros are still there. No matter what happened to them in history. So to bring about that resilience that they’ve had as a people, to be there even if they’ve gone through the hard times, I then repeat that motif. It becomes my motif that I’m using in the screen print. And I print it over and over again, making them feel like they’re there and they’re commanding enough space. And I call this one ‘Seuswa,’ ‘like grass,’ they will always be there. You know you can bend down grass, and it grows out even much greener.”

– Chikonzero Chazunguza