Ernest Dükü's 'Black Series' Is an Exploration of African Spiritual Symbols

We caught up with the Ivorian veteran artist for an in-depth conversation around his new artworks.

Ernest Dükü walks gently into the courtyard of London's Somerset House. With his greying hair spiking from his head and wearing the uniform of the fashionably ragged scholar—black suit-jacket and a scarf—he could be confused for a visitor to the 1.54 Contemporary African Art Fair. But Dükü, is an acclaimed Ivorian artist, here for the first UK showing of his new works titled "Black Series."

The 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair is the single largest exhibition of works from African artists from the continent and its diaspora in the UK. For this fifth edition, 130 artists and 42 galleries occupied all three wings at Somerset House in central London drawing in a reported 17,000 visitors. Dükü's works have been selected for many group exhibitions in his France and Ivory Coast, but less so in the US or UK. A major exhibition of his works in Abidjan is being planned for 2018.

Born in 1958 in Ivory Coast, Dükü attended Abidjan's Fine Arts School in the late 1970s before moving to France to study architecture and aesthetics and sciences of art. He now divides his time and practice between both countries though his work is known for transcending way beyond present geographical boundaries and time spans.

Dükü's works are highly distinct negotiations between installation, sculpture and painting which he has described as "sculpted-paintings." It was while a young student at the Fine Arts School in Abidjan that he rejected the two dimensions of the canvas and began to "focus on mural decor to extract a technique that allowed me to be in the feel of the painting without being in that of the easel."

This new technique was needed to accommodate his preoccupation with Akan goldweights, their signs and symbols. His interest later expanded to include the ideographic heritages of Ethiopia's Amharic, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Nigeria's Nsibidi, Mali's Dogon and Tassili rock paintings spread across parts of Algeria, Libya, Niger and Mali.

Old Masters whose works have been as influential include Christian Lattier, the Great Ivorian sculptor who adopted traditional weaving techniques to create highly distinct works using stone, wood and wires, the most famous of which is "The Chicken Thief or The Victory of the Samothrace" (1962); and Bruly Bouabre (later Cheik Nadro) who invented approximately 450 pictograms which he used to translate the oral traditions of Bete peoples of Ivory Coast into writing in the 1950s.

Dükü's "White Series" explored the history of the African continent largely through the physicality of signs and symbols and their essential natures which, in turn, led him to the spirituality contained within them. This move to the spiritual marked a new progression in his work which he's themed as the "Black Series."

Our interview took place in the (S)itor section of the exhibition which had three of Dükü's new works on display, as well as works by sculptor Ndary Lo and photographer Oumar Ly, both well regarded and Senegalese.

But are these progressions in his work confined to his practice as an artist or if indeed they also mark changes in his own personal life, and to what degree? "The two are linked," Dükü tells OkayAfrica. "There's an artistic practice that questions religious chaos and at the same time, there is a personal journey that allows for an understanding of this religious chaos."

"The absence of all color is closest to black. From this color, you can extract all other forms of color."

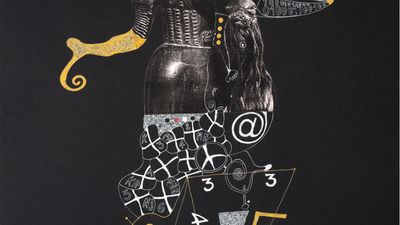

In the "Black Series," a somber, contemplative mood is set by the pitch-black paper which contrast sharply with the mainly white thread-work in shapes and figures that are difficult to identify as any one thing.

Three of the new sculpted-paintings were displayed at Somerset House and next to each other. Upon looking, the white forms on a jet-black surface at first give the impression of real objects, as is the case with FA.LUX.OR Komian @ Amaatawalé shuffle (2016) which looks like a big untidy ball of white knitting wool with a cable sticking out of it. Or very much like a masquerade in ornate white costume with its feet exposed. Stringed to it and held aloft is a baby with just one foot that is disproportionately big for the baby's size.

The jumble of anthropomorphic features, tiny drawings and shadings in white chalk, graphemes, dots of bolder colours in green, purple and red, knotted strands protruding from the main mass make for a constellation that boggles the mind, and will require the viewer to wait and ponder on the constituent elements in order deciphered or simply appreciate in some detail.

"I think that with symbols comes the memory of humanity."

No easy meanings come forth, from the work but also from one's mind on account of how dense the images are. I have found it more helpful to accept defeat, and be open to any meanings—whether paltry or profound, immediate or delayed—which the work offers. In Dükü's words, "I think that this path towards what I call 'the Exploration of Quantum Physics in the Entire Universe' has led me to better understand Akan tradition. There are links between the two."

Another cycle has emerged in Dükü's works, as observed by his curator and dealer Sitor Senghor and great-nephew to former Senegalese leader and intellectual, Leopold Senghor, who says that as a young artist, Dükü decided to focused on painting and sculpture as he didn't like drawing, most of which he would squeeze and throw away. Over time he returned to drawing, on Chinese crisp paper this time which he would squeeze and draw on, "so it was a sort of exercise which lead now to this "black series" which is more simple and really goes to the essence of his work."

Dükü's adoption of a black palette to mark a new transition from a white one could be seen as an easy or artificial imposition. Not for Dükü who insists that "the density of all things is seen in black. The reality of the density of all things is that they all initially begin with the absence of color. The absence of all color is closest to black. From this color, you can extract all other forms of color."

He continues, describing the color black as "atomic" but he may also be referring to the composite images and inscriptions that make up a sculptured-painting like FA.LUX.OR Komian @ Amaatawalé shuffle, and about which he says, "When I use symbols I try to have a sense of them and i look for the history of these symbols to translate it in my work, but I think that with symbols comes the memory of humanity. I use them to make sense of what's happening presently and in the past."

Even the titles of Dükü's works comes leaden with different levels of complexity. Examples from the "Black Series" include K.N.H.R. équilibre Kamaatawale @ Boson interdit (2016), Something else @ tombê de KARNAK (2016), and Awale shuffle @ l'énigme des enlacements (2016).More than being simply distinctive, these composed titles—typically a mixture of different African languages, as well as French and English—are intended to "create sounds, the sound of the world. I believe that the readers of the title should have the same emotion they do when they hear a song."

The polyphonic density of pygmy music from Central Africa could not, one imagines, make for a harmonious pairing with the homophonic texture of classical music from the West. Dükü has a peculiar habit of simultaneously listening to both forms while working because it will "also mix multiple levels of listening. It assists in enhancing the complexity of my work. I create distance between the music forms and whatever it is I am doing."

Asked what he has observed about visitors' reactions to the "Black Series" during the 1.54 fair, Dükü beams, "I'm very happy because people are often surprised and those that have followed me see that I have put more depth in my work and gone in a new direction. People recognize that i have gone further in my research".Translation of Ernest Dükü's quotes from French to English by Audrey Lang.