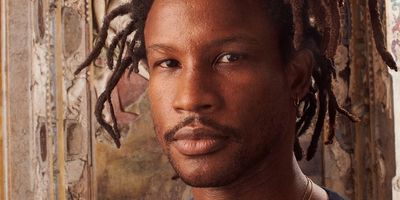

Filmmaker Akinola Davies Jr Explores the Sweet Spot Between Nollywood & Hollywood

Winner of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, London-based Nigerian filmmaker Akinola Davies Jr speaks about his experimental film 'Lizard', what belonging looks like and the overlap between Hollywood and Nollywood.

In early February, the jury for the short film competition at the Sundance Film Festival announced the Nigerian film, Lizard, as the winner of the Grand Jury Prize, the highest honour for that category. Thirty-five-year-old Akinola Davies Jr, Lizard's director and co-writer (with his brother Wale, better known as Tec, one half of the rap duo Show Dem Camp) accepted the prize from the United Kingdom, a country he has called home since the age of 13.

Lizard follows the adventures of an eight-year-old girl, Juwon (Pamilerin Ayodeji) who is kicked out of Sunday school service and goes on a tour of the massive compound where she witnesses firsthand the dynamics at play in and around a Lagos Pentecostal megachurch. Davies Jr makes use of elements of magical realism to thrust audiences into the world of this innocent as she grapples with the images she comes in contact with. The film closes out in a climactic act of violence that recalls Davies Jr's memories of growing up in a country under censorship and military dictatorship.

With this Sundance triumph, Davies Jr became the first Nigerian filmmaker to achieve this distinction. However, he is no overnight success though. Born in London and raised in Lagos, the multi-disciplined artist attended school in the English countryside and has been grinding for a while now. The bulk of his creative work—music videos, fashion films, experimental films—have navigated aspects of belonging and existing in some kind of "middle".

In 2017, collaborating with photographer Ruth Ossai and stylist Ibrahim Kamara, Davies Jr paid homage to his Nigerian roots for French luxury brand Kenzo in a video film titled Unity is Strength. He has participated in the Berlinale Talents and opened his first solo show at Art Basel in Switzerland. He is also a prolific music video director, shooting visuals for British acts, Larry B and Mischa Mafia.

We caught up recently with Davies Jr via Zoom from his home in London.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

I saw Lizard at Sundance and it is impressive but also quite the head-scratcher. How does an idea like that come to you?

The inspiration for Lizard was growing up in Nigeria in the nineties. Everything but two moments in the film happened to me in real life. All I really did was collect these childhood memories of mine and merge them into my understanding of what you can do with a short film. The starting point for me was an experience of us getting robbed at gunpoint at church once and I kind of worked backward from there. I don't have any ill feelings of growing up in Nigeria and I won't say I romanticise the brutality of some of those moments. But as a child, you don't know any better and your experience is your experience. I grew up in Gbagada, in Lagos Mainland and we went to church in Ikoyi and Ilupeju. I was [and] still am a very curious person so a lot of it was wandering around, getting kicked out of Sunday school. I always found church services tedious so I would look for how to entertain myself.

When you decided for certain that you were going to move forward with the idea, what was it like putting it all together?

I met the brilliant people at BBC Films and I was trying to show them this other project I had which was basically a glorified music video. They passed on it and told me they wanted to make a film. At that point, I was like why would you want to make a film with me? I had only ever made music videos, never a film. They assured me they had seen my work and believed I could do it. I pitched a film that was my idea of what I thought they would want. Ultimately, they said yes but as I watched some more short films and did more research, my plan began to change. When I make something, I want to put my heart and soul into it so if I never get to make another one, at least I can be proud of myself. I wanted to pay homage to growing up in Nigeria because I had never seen it done in a way that I could relate to. The films I saw did a lot of talking down to kids as opposed to seeing the world from their perspective. Children have fantastic imaginations and if you think to yourself, where can you put a 10-foot CGI lizard on-screen and justify it? It has to be from a child's perspective otherwise the film becomes a Nollywood-ish black magic kind of thing which isn't what I was going for at all.

"I wanted to pay homage to growing up in Nigeria because I had never seen it done in a way that I could relate to."

Interesting…

Also the three-act structure and the way we consume film is very European and America-centric. African filmmakers have been making incredible films in a diversity of challenging ways for a long period of time and maybe we don't always get to see them but the Sembènes and the Diop Mambétys were making non-linear linear films. So the Western-style will tell you to do it this way structure-wise; a beginning and an ending and a middle section but as an African filmmaker, I feel like you don't have to do it their way. People can figure that stuff out and if they cannot, then they can put whatever they feel into that moment and it works.

Did you always know you were going to put in a 10-feet size CGI lizard in your film?

That's funny. I knew I was going to put a lizard in there as the story developed. That is one of the first things I knew would happen. I wanted to have an aspect of magical realism and I have always been fascinated by lizards. People ask me what the story with the lizard is and I am like I don't know. But why not? I grew up on a television show called Tales by Moonlight and in these stories, humans and animals existed side by side and it was the most normal thing ever for a man to converse with a turtle or a lion. No one raised a brow. That's the kind of storytelling I was used to. I insisted on working with Nigerians, shooting in Nigeria, and having my story be as authentic so that it can sit beside something like Tales by Moonlight. If you saw Tales by Moonlight, this film will not feel like a stretch. For European storytelling, everything has to make sense to a large extent but in African proverbs, for example, it doesn't. You get the gist of it by understanding it is all part of a larger story.

Philippe Lacôte's Night of the Kings, which also played at Sundance, is concerned with the vitality and inconsistency of oral storytelling traditions. Interesting that both films even though thematically different, sort of overlap in this regard.

On the one hand, we have grown up on a diet of Western cinema and maybe there is a generation that thinks that is the only way to be telling stories. But in contrast, you have Nollywood and Nollywood tells its own stories its own way. There is this tension where people talk down on Nollywood because it has its own aesthetic going on that not everyone understands. But I think at some point both cultures have to start having a conversation. The sensitivities of Nollywood and Hollywood at some point have to overlap.

"The sensitivities of Nollywood and Hollywood at some point have to overlap."

You grew up in Nigeria, then moved to the UK where you live and work. Do you feel that people like you are poised to lead these conversations and blend these cultures?

The question is: are we going to try to do Hollywood in Africa or are we going to want to keep our own version of storytelling? For me, it is both. I don't watch a lot of Nollywood but I would love to think that Lizard is an extension of what it means to make a Nollywood film in a sense. Both retain the affinity for the mythological even though Nollywood is skewed in a basic good vs evil kind of way. With my films, I just want to honour who we are and how we tell our stories. If we take the aesthetics from the West and put in our storytelling gusto, I feel like it is more dynamic. Like the way that Night of the Kings jumps from A to B to Z and back again, but it remains incredibly easy to follow. That feeling is like listening to your mum or aunt tell stories.

This may be an unfair judgment, but I wouldn't expect a filmmaker in your position to have such fond feelings for Nollywood. In my experience, the urge for filmmakers like you is to distance themselves from Nollywood-as-genre.

I think maybe there is an element of feeling like an outsider because I have lived in the UK since I was 13. There are a lot of things I think are of value in Nigeria that maybe you don't see value because you are so close to it and I am from a distance. If someone calls me a Nollywood filmmaker then I accept it. It is what it is. Nollywood is still very young compared to other filmmaking cultures and at some point, if we all work at it, it is going to mature. I would like to be associated with Nollywood and be part of the conversation on its evolution. I know that is a grand thing to say because I am still fresh and obviously just because I won an award doesn't make me an expert on Nollywood or anything, but I have seen a lot of value in the craft, talent and workmanship over there. I think it should be allowed to grow and make mistakes and evolve. I hope Lizard can be considered a Nollywood film and I wear that with pride. If I have any spere of influence I would hope to inspire the next generation of talent to make films that are more refined but still within that space.

I suppose I should ask the question that everyone who has seen Lizard has on their mind. What is going on really?

Hahaha! What do you think is going on?

I feel like the film takes us through the mind of this child, asking us to see the world through their eyes, with wide-eyed innocence and plenty of imagination. And it reminds us of the ways that kids are constantly processing the information overload available to them in a way that makes sense specifically to them.

That is pretty accurate, and everyone has a different take, but you just summarized it pretty well, maybe even better than me. I enjoy hearing other peoples' opinions of it because it helps reinforce my own opinions. I had a lot of intentions that I wanted to explore not necessarily knowing why. I think that children are brilliant and resilient and are great mediums to see the world through and great engines for storytelling. Girls get policed more often than boys so it was important for me to engage that period of curiosity before everyone starts telling you what to do and how to feel. A lot of things were happening to me as a kid with this sociopolitical background of violence and trauma. I love home and now wish it were different but that is just the way that things were for me. For the adult, I wanted to make something that you can watch and understand immediately but still be disoriented by it. And for children, something they could watch and just be excited [about] without necessarily appreciating fully what they are seeing.

Your brother, Tec is a rapper. What is that creative collaboration like and are there other gifts he has hidden away that we should be aware of?

He is best known for his work with Show Dem Camp but my brother is an artist first and foremost and rap is just one of the outlets for his artistry. The rapper is a poet and a storyteller, and my brother was the only person I knew who had written a screenplay when I conceived Lizard. We get on famously, he is my best friend and the one person I want to tell stories with. I respect people who do not think of themselves in this singular capacity and are willing to explore several facets of their talent.

Follow Akinola Davies Jr on Twitter and Instagram.

- These Are The Best Nigerian Films of 2020 - OkayAfrica ›

- Netflix Launches 'Netflix Naija' and Announces First Nigerian ... ›

- Watch the Trailer for Upcoming Nigerian-American Fraternity Drama ... ›

- 'Namaste Wahala' Is the Nollywood Meets Bollywood Crossover We ... ›

- The 20 Best Nollywood Movies of All Time - OkayAfrica ›

- The Best Nollywood Films Streaming on Netflix Right Now - OkayAfrica ›

- Akuol de Mabior Takes Her Film from Sudan to Berlin - OkayAfrica ›