How Is Digital Technology Changing Africa’s Cultural Landscape?

World Policy Institute's Nahema Marchal looks at digital technology and its impact on arts and culture in Africa.

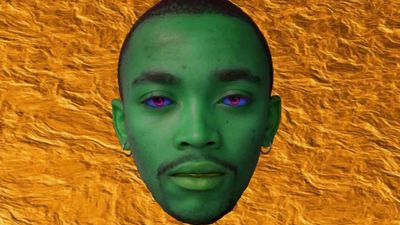

Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Chatbot Avatar. Courtesy of the artist.

Okayafrica and the Program for African Thought at the World Policy Institute present the third in a series of stories at the intersection of politics, policy and culture in Africa. In the third installment, WPI's Nahema Marchal looks at digital technology and its impact on arts and culture on the continent.

Digital developments are happening at a remarkable pace in Africa. In just over ten years, mobile adoption has skyrocketed, and the declining costs of handsets and broadband mean it is now easier than ever before for thousands of Africans to get online. From mobile banking to social networking, news and health apps, internet access via mobile devices has ushered in a revolution in information sharing, particularly in tech-savvy nations – South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria – where usage is widespread.

But despite the increasing role of information communication technology (ICTs) in people’s daily lives, few people are exploring the less conspicuous side of this digital boom: its impact on arts and culture.

It is partly to fill that void that Tegan Bristow – a digital media artist and the Head of Interactive Media at the Wits School of Arts at Wits University in Johannesburg – developed her research on digital and communication technologies as mediums of artistic expression.

“While teaching Visual Arts at Wits, I realized very quickly that my students had no framework for understanding new media and technology in the African context. Most of what they find in textbooks is strongly Euro-American, and does not accurately explain their experience with technology,” she told me when I spoke to her on the issue.

Yet, unbeknownst to the Western art market, contemporary African artists have been experimenting with digital technology for many years. Collage artist Nkiru Oparah for example, utilizes the digital space to reclaim, subvert or refashion typical representations of Africa, often by superposing ethnographic documents and digital imagery. While others, like Nolan Dennis or Bogosi Sekhukhuni, focus instead on animation as a new conduit of storytelling, that can playfully challenge conventions about how and from where information about Africa comes.

Nkiru Oparah, via African Digital Art

For Bristow, that’s precisely what makes the digital arena such an interesting space for African culture. Beyond its obvious social and economic implications, it is also a site of cultural resistance to globalized systems of knowledge. “Digital and communication technology is something that has unfortunately been very reliant on the violent subjugation of African culture and African societies,” she explains, “but in practice, it has given rise to very distinct ‘cultures of technology’, linked to specific histories, and to specific experiences of oppression and resistance.”

“In South Africa, for example, where the government was one of the first to use technology to keep track of people, there’s a very particular visual culture that comes out of township life – one of representation and differentiation, with a sort of low-fi, glitch anti-commercial aesthetic – whereas in Kenya, it is more the oral tradition, storytelling, and social justice engagement that dominate the space of digital practice.”

It is a common view to see technological innovation in Africa as a direct legacy of colonial and postcolonial intervention, rather than a product of genuine, fruitful interactions between new technologies and indigenous practices and customs. Sadly, this lack of awareness together with an ongoing media obsession with the “digital divide” – a term coined in the mid 1990s to address uneven access to digital resources – mean that, more often than not, African people are viewed as passive recipients of foreign R & D, when in reality, “if digital and communication technologies are these great modular thing, they only augment systems of knowledge transfer that already exist quite naturally and quite substantially within Africa”.

Today, countless projects are breaking social, geographical and infrastructural borders by redefining what is means to be a citizen, an advocate, an artist or a writer in the digital age. 2012 saw the launch of Badilisha Poetry X Change, for example, the first and largest digital archive of pan-African poetry in the world. Keeping up with Africa’s rich tradition of oral poetry, the site, accessible via mobile phones, serves as a platform for poets to showcase their work in both written and radio format.

Zamani Project, 3D Model, x-ray of the Apedemak Temple (Musawwarat, Sudan)

In recent years, spatial digitization has also gained prominence as a tool to preserve heritage sites from cultural terrorism, vandalism, theft and decay. The Zamani Project, spearheaded by Dr. Heinz Ruther (professor at the University of Cape Town), uses spatial data to create striking 3D models of African heritage sites, with the ultimate vision of an “African Heritage database for the preservation of the past for future generations”. Since 2004, Dr. Ruther and his team have recorded 40 sites in 14 countries in Africa and the Middle East, and scanned and modeled more than 150 individual buildings, monuments and rockshelters.

By making information that was previously unknown or only available to a fraction of researchers available to all, “digitization, in combination with advances in communication, has changed the speed at which this knowledge is spread as well as its range,” notes Ruther. And this is but one of many examples. One could also mention DASI (Digital Archive for the Study of pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions) or the Virtual Freedom Trail Project – a community archive and online museum seeking to map the heritage of liberation struggle in Tanzania.

Given the growing hold of foreign investment in Eastern and Southern Africa, and of what some call the “scramble” for African indigenous knowledge, it would be easy to see digitization projects (most of them funded by foreign organizations) as Trojan horses for a new wave of cultural imperialism. But if these efforts are no panacea for the vast inequalities and issues of access and social resources that remain within the continent, they nonetheless reflect genuine efforts to assume greater control over African arts and culture, and save them from marginalization.

More importantly, they invite us to go beyond the idea of digital divide as a simple split between haves and have nots, and interrogate instead the role that language (the domination of English online), digital literacy and education might play in stopping Africans everywhere from benefitting from these advancements. Who do those histories reach? And who is enlisted to write them? Only by asking ourselves these questions can we begin the difficult work of ensuring fairness in access to African digital resources.

Nahema Marchal is a Program Assistant at the World Policy Institute.