How I Found Black Queer Love In A Heterosexual Society

I didn't expect to fall in love with a woman, but I did. Does that make me a lesbian? Bi-Sexual? Or something else entirely?

I was often told that university is where I’d meet the man I’d spend the rest of my life with. If anyone had told me that I’d fall deeply in love with another woman, I would have laughed at them. From the time we are young, we are taught who we are allowed to love and what kind of love is ‘normal’ resulting in a one dimensional view of what romantic love is supposed to be like.

I met her—let’s call her Zee—at the beginning of my last year at Rhodes University. When we met, love and relationships were the furthest things from my mind. But after several run-ins, Zee and I decided to get to know each other better. We agreed to meet up that Saturday afternoon. When she didn’t show up or call, I felt bleak.

In all fairness, I shouldn’t have been THAT upset because we weren’t even in a relationship (we were still playing cat and mouse games). Later that evening, when her name appeared on my phone screen, a giddy and warm feeling crept up inside me, but remembering how she'd stood me up, I rejected her calls at least nine or ten times.

“Nana I’m here, please come outside’’ she texted me. I stared at the message and that warm feeling returned. I walked down three flights of stairs to find her sitting on the bench outside my residence, when her eyes met mine and when she smiled I momentarily forgot why I was upset in the first place. In that very moment, I knew that I felt more deeply for her than I was willing to admit. She apologized and caught me off guard when she asked me to ‘officially’ be her girlfriend and of course I said yes.

I had only been in relationships with heterosexual men before being in a relationship with Zee, but she was the first person I felt so deeply for, the first person I uttered the words ‘I love you’ to and it felt right, it felt good. We define love differently, for me love is the early morning and late night laughter we shared, the in-depth conversations about what it means to be black, to be a woman. Love is when we stood in solidarity- using our bodies as barricades during the #RUReferenceList Protest. Love is when she allowed my torrent tears to soak through her shirt when I felt suffocated by patriarchy. It’s when she embraced me so tight it felt like the broken pieces inside started to mend. Love is when we sang along to Ringo’s "Kum na Kum" on Sunday morning, when she held my hand as we walked down High Street and when she kissed me on the forehead as we stood in the queue at Pick n Pay. Love is when she whispered: ‘ndiyakuthanda nana, and khumbula andilahleki- you’re stuck with me kaloku” (I love you nana, and remember I’m not going anywhere- you’re stuck with me).People were surprised when they found out that I was in a relationship with Zee. “So, you’re lesbian now?” is the frequent question people asked me based on the assumption that because my girlfriend identified as a lesbian, I was one too. I was also often told: “but you don’t look like a lesbian, you’re such a girly girl.” A close friend of mine told me that she never expected that I of all people would be in a relationship with another woman—that I was one friend of hers who she was completely certain was heterosexual-she never expected that I’d ‘‘play for both teams.’’

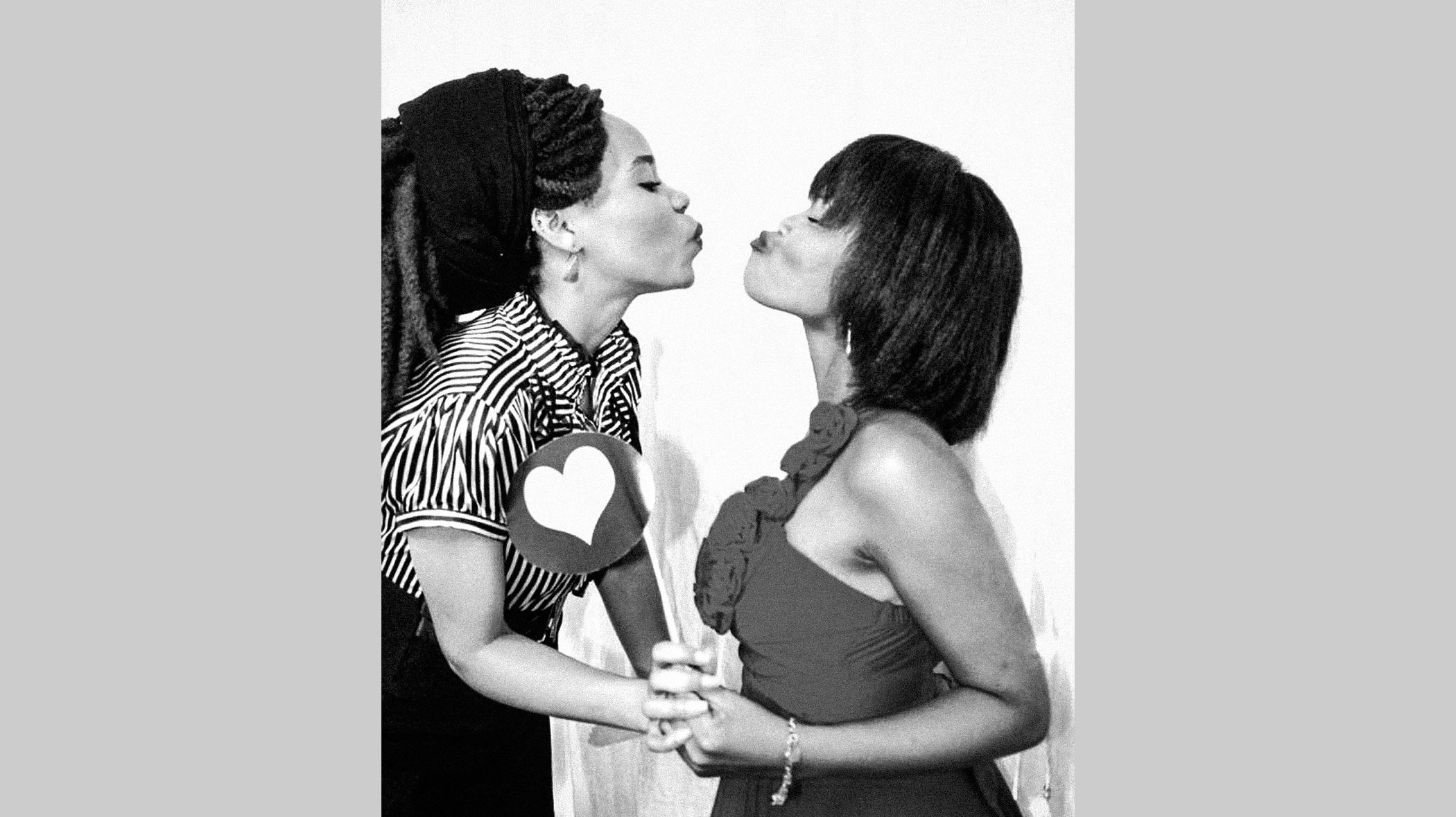

The students from my residence curiously stared at us as we often sat outside on the bench while Zee smoked. Over lunch in the dining hall, those that were brave enough asked me if Zee and I are really “dating-dating” and who is ‘’the man’’ in the relationship—"we all know between Caster Semenya and Violet, Caster is the man...” Rhodes University has been dubbed the liberal university, a place where one can unapologetically be yourself without judgement, so I was actually surprised at the ignorant questions. The more they saw us together (holding hands and stealing kisses from each other) the more they got used to the fact that we were together—they even gave her the name ‘‘Sista Bae” and asked about her whereabouts when she didn’t come around to visit anymore.

I didn’t feel the need to label myself within the #LGBQTIA umbrella, in fact I hadn’t given it much thought until I was constantly asked if I’m lesbian. I found myself confused. I couldn’t figure out what I identified as, whether I was a lesbian, or bi-sexual. This need to position myself, to claim a label grew. Zee and I had a lengthy conversation about it, and she helped me understand that I wasn’t a lesbian. Unlike her, I had been in relationships with heterosexual men and still found myself somewhat attracted to them. That left me wondering if perhaps I am bi-sexual or ‘a double adapter’ as my heterosexual male friends called me. The ‘bi-sexual’ rigid label didn’t sit well with me either, calling myself lesbian or bi-sexual is too specific for me. Lesbian implies that one is only interested in other women and bi-sexual implies that there are only two genders (male and female). Also, I detest the constant comparing of one term to another.

I am divergent, fluid, queer. I first came across the term “queer’’ a few years ago. Back then, I understood it to loosely mean “anyone who does not identify as heterosexual, hetero-romantic or as cisgender.” The more I read and spoke to others about being queer, the better I began to understand myself. Once I had embraced my queerness, I was at ease with myself and being with Zee. I didn’t look at her as a lesbian, I looked at her as another human being, as someone I had grown to love and someone who loved me. I let her in. I let her see me naked—not just in terms of taking my clothes off. I ripped off my mask and let her see my wounds and scars. She walked through my mind, and saw parts of me that I didn’t even know existed. With her, I felt something I had never felt before. I felt secure because she knows me intimately—because she knows my depth.

Zee is my first love. She was the cause of my writers block and somehow had the ability to resuscitate it. They were right about one thing: one can find love while at university, but that love doesn’t necessarily have to be heterosexual; it can be black queer love too.

After a night out with friends, I got home, and half intoxicated switched on my laptop and wrote this poem:

Yearning for You

She lost herself to the beat on the dance floor,

And momentarily forgot about you

Until they played one of your favourite songs

Misty-eyed,

Surrounded by people

But felt loneliness wrap itself around her like a blanket

Blistered feet,

Of smoke her hair reeks.

As the wine slowly withdraws from her system,

It’s the warmth between your breasts she yearns for,

It’s your voice she aches to hear.

It’s the map of Azania inked on your back she itches to trace

With the tip of her finger

In bed she lies, repeatedly listening to Mafikizolo’s ‘Emlanjeni’

And browses through photos that awaken fond memories...

You know what they say about distance and the heart.