A Conversation with Ato Malinda and Yinka Shonibare MBE on Exploring Identity in “African Art”

Ato Malinda and Yinka Shonibare MBE talk to Okayafrica on how they address the conflict of cultural identity and artistic practice.

What exactly is African art?

The author of a recent Okayafrica article on 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London challenged the layman's definition—art made by an African artist—stating, “It often seems that the artist’s identity is enough to be categorized as African art, rather than the substance of a piece.” This is true for artists like Man Ray and Pablo Picasso, of American and Spanish descent, respectively, who both fetishized African ceremonial masks, yet are not categorized as ‘African artists’ or as making ‘African art.’

The separation of art and African identity is murky, and the pairing not always incorrect. The association becomes problematic when assumptions about the continent guide the cultural classification of the art and artist.

Two artists whose recent works challenge the linkage of identity and art are Ato Malinda and Yinka Shonibare MBE. Both artists exhibited in London in October—Malinda at 1:54 and Shonibare in a solo exhibition elsewhere in the city. They are also the honorees of the First Annual African Art Awards.

In separate interviews each artist revealed to me how they address the conflict of cultural identity and artistic practice.

Malinda is a multidisciplinary artist born in Nairobi. Through her diverse practice she investigates the hybrid nature of African identity, contesting notions of authenticity, as well as focuses on gender and sexuality. Recently Malinda participated in an artist residency at the National Museum of Denmark that examined the construction of memory: the thoughts and recollections produced by history and self-perception that form the institutionalized cultural knowledge which shapes our collective thinking, and inevitably the biases (familiarities) that are consolidated as historical fact.Malinda researched how African objects are exhibited in Western museums. “I was looking at the idea of synecdoche, meaning when small parts of a culture are exhibited as the whole culture. That happens a lot in ethnographic exhibitions,” she explains.

The museum’s display of African art was horrific. Malinda notes the exhibit was simply titled, Africa; individual artifacts weren’t labeled at all; and it was also monochromatic—everything was brown, both the garage sale-style arrangement objects and the walls that segregated them from the open museum space.

Malinda also discovered the exhibit had been untouched since the curator first corralled the objects 20 years ago. And, in the 10 years prior to her arrival, that the curator had since retired and died. “I was laughing out of incredulity,” she says.

In response, Malinda created a performance piece to challenge the construct of ‘brown.’ She selected participants, who were majority European, to paint blocks in the same shade of brown, over and over again. This illustrated how the perception—the memories—of Africa remained constant despite change (i.e. a new coat of paint), particularly under the European gaze.

Of course, the objectification of “African art” in the museum setting is not an absolute. A salient example was the recent exhibitDisguise: Masks and Global African Art at Brooklyn Museum. Disguise paired traditional masks with contemporary reinterpretations of masquerade by artists from Africa and the Diaspora in an “immersive and lively installation of video, digital, sound, and installation art, as well as photography and sculpture.”

Shonibare’s epiphany of the tie between African art and African identity came to front in university in London, when his instructors were befuddled as to why their African student was not making ‘African art.’ Bewildered himself, since he thought that artists simply create art and not a cultural subgroup of it, he began researching the artistic application of one of the most visible hallmarks of the African continent—the wax print.Wax batik print, which, despite its pervasiveness on the continent, is actually of Dutch and Indonesian origin, became Shonibare’s trademark. He uses the wax print to represent the flexibility of the African identity, colonialism and post-colonialism within the contemporary context of globalization.

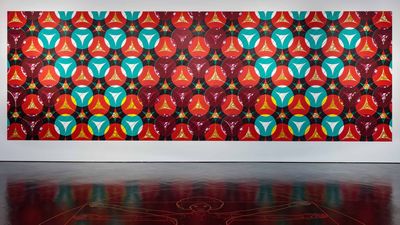

Whereas Shonibare had previously incorporated the physical textile into his artwork, he presents a different application of the fabric in his new show, …and the Wall Fell Away. Now, he paints only the patterns from the fabric and abandons the physical material. By leaving only a trace of his trademark batik motifs, Shonibare gives a personal insight into the complexities of identity, nationality and colonial history, as the exhibit’s press release explains.

The artist, who was born in London and raised in Nigeria, also typically incorporates movement in his work (like his choreographed masquerade, Un ballo in maschera). He says about his affinity for movement, “I like things to be visually dynamic, not just formally but the narrative of immigration and physical movement that are present in work anyway.” The title of his exhibit refers to “the current global-political situation and attacks the reason that foreigners need to be kept out.” He adds, “I wanted to take those walls down and dismantle the boundaries [of Western understanding].”

Like with art and cultural identity, migration has suffered an intimate relationship with “brown.” Through art, Shonibare assumes control of this narrative.

Art fairs like 1:54 and consciously-organized art exhibits placate the Africa/African artist/African identity mélange by inspiring a definition of Africa free from its “historical baggage.” Contemporary artists take charge in addressing identity, too. Africa the monolith does not exist. And also fictional is the singular identity of “African art.”

...and the Wall Fell Away is on view at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London until Nov. 11, 2016.

This fall, Shonibare has four different solo exhibitions running concurrently on three continents—a first for the artist. He is also part of the group exhibit Senses of Time: Video and Film-Based Works of Africa, on view at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art until March 26, 2017.

Nadia Sesay is a Sierra Leonean based in Washington, D.C., traveling the world to indulge in art. She is Editor of BLANC Modern Africa, a magazine on contemporary art and culture inspired exclusively by Africa and its Diaspora.