An African In Need: How I Learned to Stop the Self-Hate and Love My Africanness

In this personal essay, Joan Erakit opens up on her continued struggle with her identity as an African living in the diaspora.

DIASPORA—My mother stood in line at the store counter waiting to be helped by the white woman with short, yellowish hair behind the sign that read ‘Customer Service.’

This was not the first time we had been to the Kohl’s store with an issue, but this was the first time my heart beat profusely because I knew my mother was nervous. I never liked when she got nervous because to me, this communicated a problem for which a parent could not fix was at hand.

My dear mother had interrupted my "Sister, Sister" marathon to drag me with her to the Kohl’s store for a fate every immigrant child must face: she wanted me to speak on her behalf with the customer service agent because she didn’t want to be embarrassed by her own accent.

Let me explain.

At the time, my family and I were about 7 months into living in the United States having migrated from Nairobi. During those first three or so cold Minnesota months, my parents had quickly realized that the first thing any American said to them after they had spoken was: “I’m sorry, what did you say? I can’t understand you.”

My mom and dad had become frustrated, as adults who needed to do daily things to care for their young family, from being so often misunderstood because of their “accent.”

I had been brought up in an English, Swahili household and gone to a British school for most of my young life. At the age of 7, my parents enrolled me at Rosslyn Academy in Nairobi, a Christian American school they thought would help me better assimilate into an American community once we moved a few years later.

My accent for the most part was British/American with the occasional plea in Swahili when I begged my parents not to beat me for running my mouth. Alas, that particular cold day in Minnesota—feeling tired of being looked at a certain way—my mother dragged me to the store to speak on her behalf because she believed that the Americans would understand her daughter’s English.

This was the first of many ordeals for which I would be subjected to, and for which would brew a hatred of my own “African-ness” as years went by.

“Jo, tell the woman what I told you,” my mother whispered to me as we approached the counter.

I took a deep breath and started the, “Hi, my mom would like to return this shirt for my little sister because…” a wave of embarrassment creeping up the back of my spine as I felt my own mother’s shame near me.

I hated being an African.

I hated that my parents had an “accent.” I hated that everyone in Minnesota knew that we had come from Africa and that in class, they would chant “Coming to America!” every time I walked by referencing the Eddie Murphy film.

Elders often say that the things people say to you when you are young last a lifetime and in most cases, form your opinion of yourself. It wouldn’t be until years later that I would understand this notion in its entirety.

Like any other person, I was a difficult teenager. I went out of my way to defy and deny my African parents. I refused to sign my last name on any document, often just listing initials because I didn’t want people to ask me about my origin. I betrayed my parents by speaking ill about them in the presence of other, more dignified Americans as people who need to better assimilate into the culture and stop complaining about being stereotyped, never once realizing that one day I would face far worse injustices because of my skin color.

I made sure never to invite friends over to my house lest they smell the “African-ness” of our daily meals—curry, cassava leaves, onions and meat that had been boiled for hours the day before. God forbid any of my cool, new American classmates saw my father walking out of the house and into the snow in his rubber slippers to collect the mail on Saturday afternoons, or my mother wrap her kanga twice before taking out the trash, sounds of Lucky Dube blasting from the speakers behind her in the doorway.

And then one day, I met *Mary, a Nigerian girl who had just moved to the U.S. and was seated next to me in my 7th grade class. She reeked of ‘African-ness’ and I was horrified to be associated with her, let alone sit next to her in a classroom full of American boys for whom I could only dream of talking to in the hallways.

But Mary liked me, though I did not deserve it. The truth is, I had very few friendships at that time, despite my many drastic attempts to acquire them.

Mary liked me enough to look for me from across the lunchroom, her tray full of odd objects her mother had packed for her in tin foil. I avoided this braid wearing child like the plague, afraid that two Africans together in public—fresh off the boat in one setting—would surely set off a riot among our hosts.

Contrary to my teenage avoidance, Mary and I actually became great friends.

My relationship with Mary was very odd because it reminded me of my mother. Like my mother, she too had an accent and said “ting” instead of “thing” like every other American I knew. She also smelled familiar—just like my home during dinnertime. She was also wicked smart and forced me to revise almost everything I wrote thanks to her handy grammar notebook.

Naturally, I became comfortable hanging out with Mary because lets face it, no one understands you more like your own. But there were bad things about our friendship too. I found myself ‘Americanizing’ her by giving her advice on what to wear, and which boys to sit next to in homeroom and of course, when to let me speak on her behalf so that no one would hear her accent.

However, it was Mary’s relationship with her own mother that gave me much anxiety. They were as close as thieves, giggling like sisters whenever they’d offer me a ride home in the family car, a taxi her uncle drove on the weekends and which filled me with horror upon its approach of the wide, middle school driveway.

Speaking in their language, they would discuss the day’s antics, laugh without abandon and plan for the night ahead. I would sit in the backseat, looking out the window, secretly envious of their close relationship and wondering how Mary could stand to be seen with her very African mother. Her mother, like mine, had grown up in a small village under a strict Christian household.

Like my own mother, Mary’s mom lived life according to “God’s word” and made it her duty in life to publicly humiliate every child with scripture and threats of canings should they ever feel the need cop an attitude in a Target store. She was vibrant yet shy, thoughtful yet carefree and always full of private jokes—very much like my own mother.

Years later, I had a very strange thing happen.

During a conversation with a creative collaborator, the subject of going into a West African country to shoot photos for an upcoming exhibit derailed when this partner said: “Joan, I’m not sure we can just send you in as you don’t understand the culture. You’re an American and you’re going to have to first understand the context before you can head in with a camera to take photos of people’s daily lives.”

It was like taking a bullet.

I couldn’t believe that this white, American woman thought that I, a woman born and raised on the continent of Africa had absolutely no idea of the cultural context of said country. I shall refrain from repeating the four letter words that followed in a haze of anger, but I will say that the irony of the conversation provided a learning opportunity.

I had spent so much time since my teenage years in Minnesota aggressively erasing any evidence that I was an African and the prize for my diligent work was for someone—a white American—to validate my assimilation by telling me that I was now in-fact, not African anymore.

At such a point, I had won the battle, but certainly not the war.

They say that the things we were most ashamed of as children, the things that people used to taunt and bully us for, oftentimes turn out to be the things for which we seek as adults.

I realize now that in most cases, we only hate that which we long for. In my situation, I hated my ‘African-ness’ because I wanted to belong to something. I longed to be part of a tribe, a pact or an understanding of the world that was unique and inherent in my blood—one that society could not touch. In hating my mother’s bold African-ness—even when she was ashamed of it—I fostered a self-hatred for myself as a person.

I am a work in progress and, like many Africans living in the diaspora, I struggle with my identity. Writing allows me to explore themes, revisit past misgivings and reflect on the growth that has amassed thus far. A shop vendor in Harlem, near where I live, jokingly refers to me as “an African in Need.”

What he means to say is that I’m in need of a redemption that will only come once I truly reconcile my formative years as an immigrant teenager in America. Somewhere along the way, I lost the ability to explore who I was without shame. Somewhere along the way, I decided that being an American was better than being an African.

Seemingly enough, I find hope in the future and in the renewed relationship that I have with my mother.

Her grace, her patience and her honesty has allowed to me flourish as a writer and a human. Of course, she laces everything with “Gods word” and the occasional plea to not “disgrace the family.”

I can take that, especially when she speaks with her beautiful “accent.”

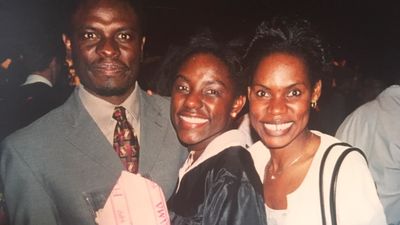

Joan Erakit is a Kenyan-Ugandan born writer based in New York City. Her work has been published by Cool Hunting, The Huffington Post, The World Post, and Marie Claire among others. She is currently shopping her first book, Meet Me In The Village, a collection of non-fiction short stories about reproductive health and family planning. You can find her on Twitter, Instagram or her website: joanerakit.com.