The Real Impact Of The American Ebola Effort: Assessing Obama’s SOTU Claims

Despite Obama’s claims, America’s real impact in fighting Ebola was too little, too late. But there’s more to the story.

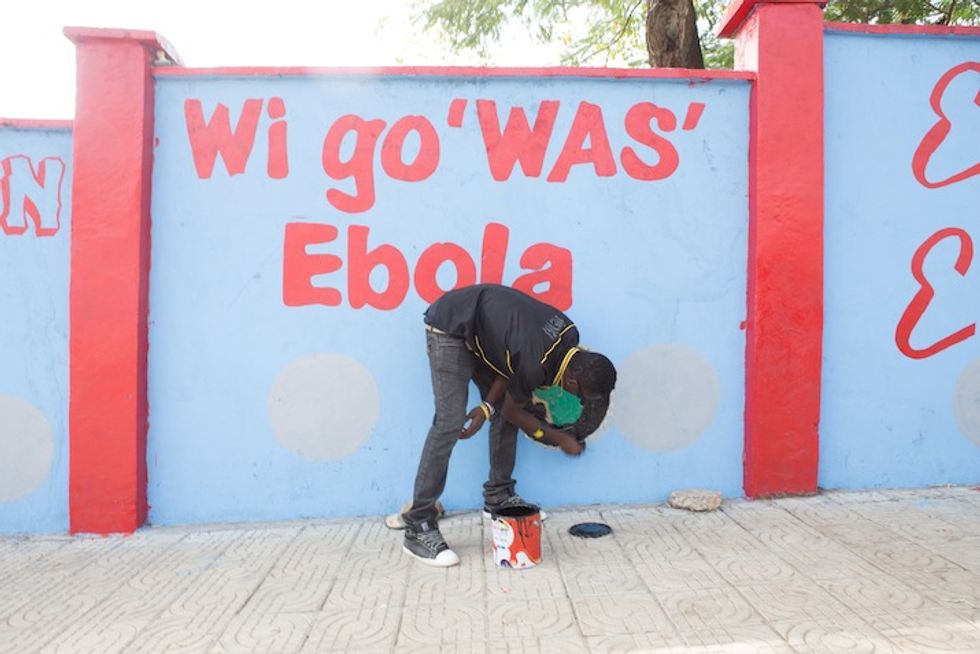

"We go wash Ebola": A man paints a wall in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Photo: Lance Steagall

On Thursday, Liberia was declared Ebola-free. But before the world could celebrate the end to the worst Ebola epidemic in history, Sierra Leone announced a new case dashing hopes that the outbreak, which has killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa, was over.

During his final State of The Union Address on Tuesday, President Barack Obamacredited the success made in combatting the Ebola epidemic to the role of the United States.

“That’s how we stopped the spread of Ebola in West Africa,” he said. “Our military, our doctors, and our development workers set up the platform that allowed other countries to join us in stamping out that epidemic.”

This caused a flurry of criticism on social media and elsewhere from both individuals and organizations who saw the American response, and the global response in general as very little and very late. The World Health Organization, for example, only declared the outbreak a public health emergency eight months after the disease started.

I was one of many local and international journalists who covered the deadly disease. I saw Liberia’s already broken health system collapsing as the number of infections rose. The government, already saturated with corruption, faced an integrity crisis. The New York Times, AP, and a few international news outlets published many articles about the deaths and suffering.

Despite the despicable images making rounds on television, the international community would not respond until eight months later. The disease by this time had affected four countries: Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. There were 1,711 cases (1,070 confirmed, 436 probable, 205 suspect), including 932 deaths according to the WHO terming the outbreak the worst ever recorded.

Donald Trump's 'Liberation Day' and Its Potential Impact on Africa

The American president is unveiling a list of tariffs that could disrupt global trade and inevitably affect African economies.

International medical charities like Samaritan’s Purse and Doctors Without Borders (Medecins Sans Frontieres or MSF) were the first responders during the outbreak. They struggled to care for the sick with the meager resources available in the early days. In June when there were no established Ebola Treatment Units, the medical charity Samaritan’s Purse was the only organization running a makeshift triage at the back of the ELWA Hospital in Paynesville as the rest of the country’s health sector struggled. I remember paying many visits there during my regular reporting. The U.S. government has come under deserved criticism for only taking the outbreak serious after two of its citizens working for Samaritan’s Purse became infected with Ebola and were evacuated to the U.S.

By the time U.S. troops were mobilized, more than 3,000 persons had died from Ebola in West Africa and America itself was at risk after a Liberian man, Thomas Eric Duncan, flew into Dallas, Texas, with Ebola in his system. As a Liberian, and understanding the respect Liberians and the government attaches to its relationship to the United States, I feel the United States response to Ebola was slow and the amount of money invested in make-shift Ebola Treatment Units could have been used to invest in a more sustainable healthcare delivery system.

Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent to build Ebola treatment centers, nine of which would later be torn down without treating a single patient. A New York Times article took the U.S government to task for this slow response stating that only 28 Ebola patients were treated at the 11 treatment units built by the United States military.

President Barack Obama’s signing into law a US$1.1 trillion appropriations act that allotted approximately $5.4 billion in emergency funding to support the U.S. Government’s response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa came in December of 2014 when the epidemic had already slowed in the three most affected countries.

But not everyone is so critical of the American response. Members of the Liberian government and many others believe that the decision to commit U.S. troops to fight Ebola in Liberia boosted the Liberian public’s confidence in the national government, acting more as moral support.

Tolbert Nyenswah, Deputy Minister for Disease Surveillance and Epidemic Control at the Liberian Ministry of Health, told me in an interview from Monrovia that the mere landing of U.S. troops on the ground to help fight Ebola, after President Obama’s announcement, was a critical turning point in the fight against Ebola.

Nyenswah said the U.S. response to the Epidemic had a psycho-social impact on Liberia’s own response to the deadly Ebola Virus and a people which once lost all confidence in the national government began to join efforts to fight the disease.

“When Ebola started, the citizens didn’t have trust in the national government, those were some of the factors that escalated the number of people who were affected and died from the disease,” said Nyenswah.

“When the United States got involved and President Obama announced the deployment of 3,000 U.S. troops; announced support and called on the international community to help the three affected countries; that brought relief that brought psycho-social and behavioral change to the people.”

He said the mere thought of American boots on the ground meant more to the people than what all the effort the government was applying to the Ebola outbreak and this released the level of pressure the government had been under as public criticism of its handling of the epidemic soared.

“The U.S. organizations like USAID, DART, gave money to national and international NGOs to support the response,” said Nyenswah.

“It was a turning point in the outbreak. The Liberian government was able to tap the resources and even though government was in the leadership, the international community complimented the government’s strength.”

In his speech, President Obama almost certainly claimed too much credit in the fight against the deadly Ebola outbreak. But what remains constant in Liberia is the confidence the people have in Washington, far more than they have toward their own government because of accountability and transparency issues. If the United States and the rest of the world had responded earlier to help West Africa in its Ebola fight, this would have reduced the level of transmission that we saw.

As of January 6, 2016, there were 28,601 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases reported in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, with 11,300 deaths according to the WHO.

The WHO stated that majority of these cases and deaths occurred between August and December of 2014. With Sierra Leone announcing a new death from Ebola, Guinea and Liberia are looking to see when this disease will finally end.

Wade C. L. Williams is an award winning freelance journalist from Liberia and a Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow at the University of Maryland, College Park.