At the 60th Venice Biennale, Ahmed Umar Revives a Traditional Sudanese Bridal Dance

The multimedia artist unveils a tradition that has been pushed to the margins and invites us to enjoy the beauty of Sudanese wedding celebrations.

Talitin (Arabic for third) is Ahmed Umar’s performance at the Venice Biennale.

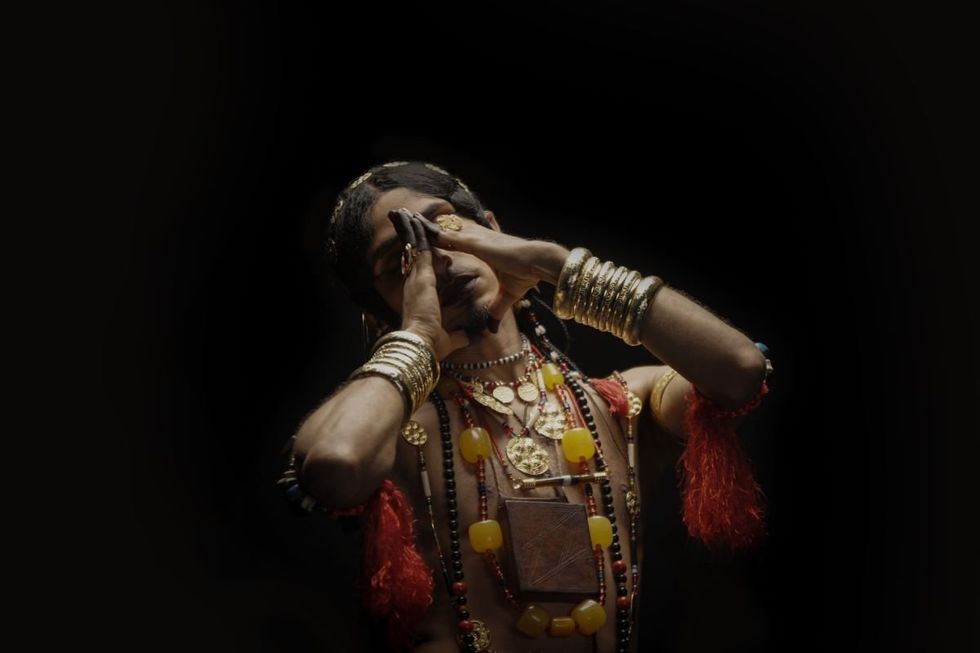

Piercing ululations, ecstatic clapping, several rhythms locking into each other, honoring the dancer in the middle of the circle. The dancer is wrapped in red garments and adorned with golden jewelry; neck lifted towards the sky, they twirl, circle their shoulders, wrists and hips, encouraged by the singer’s, “ya sudaniya, ya sudaniya, ya sudaniya.”

At the opening of this year’s Venice Biennale, Sudanese artist Ahmed Umar re-created and innovated the traditional Sudanese bridal dance. “I’ve had this project in me since my childhood,” he says in an interview with OkayAfrica. “I’ve always been fascinated by weddings and parties and the bridal dance was just the ultimate magic and stimuli for me.”

Talitin (Arabic for third) is Ahmed Umar’s performance at the Venice Biennale.

Photo by Jakob H Svensen.

Umar grew up in a Sufi family living between Sudan and Saudi Arabia, but fled to Norway at a time when being openly queer was punishable by death in Sudan. He works with different materials and across various artistic mediums, depending on the story he chooses to tell.

“I use my body to tell my stories and that comes in the form of sculptures, paintings, performances and photography,” he explains. “One of my main motivations is that my experience of being discriminated against and demonized as a Sudanese gay person should not be repeated. I see that it continues to happen and I want to use my work to stop that, raise awareness, spread love, and be loud.”

His performance of the bridal dance, which he titled Talitin, was born of the desire to participate and immerse himself in the joy and beauty of what he considers quintessential Sudanese culture; when Umar was about 10 or 11 years old, he was not allowed to witness his cousin’s bridal dance, because he is male. His title in those years was Talitin (Arabic for third), a slur that means “the third of two girls.”

Talitin (Arabic for third) is Ahmed Umar’s performance at this year’s Venice Biennale.

Photo by Jakob H Svensen.

But Umar snuck on the balcony and secretly watched the dance. “All the gold, the atmosphere, the happiness, it gives me goosebumps until now,” he remembers. “Talitin is a spot-on description for me, because I used to love being in the middle of my grandmother and all the women, learning from them without them noticing.”

Originally, Umar was looking for a woman who could perform the dance, which he wanted to document. “I see it as one of the few authentic Sudanese traditions that some women have kept alive, even though it’s underground,” he says. But he couldn’t find any woman willing, or feeling safe, to be documented dancing in the traditional way, displaying her beauty and wealth while choreographing the newlyweds’ journey from courtship onwards.

In his grandmother’s generation, a bride would dance out in the open, with the whole village in attendance. “At that time, there was no shame about the body and no sexualising of breasts, they were just a part that has a function,” says Umar. Nowadays, after decades of dictatorship and a strong Islamization and Arabization of Sudanese culture, it is almost never performed.

So, even though he doesn’t have breasts, which according to him are essential to the dance, Umar decided to learn it himself. “Collecting the costume took about seven years,” he shares. “My reference was a traditional garment my grandmother made for her daughters, which I last saw when I was a child. When I returned to Sudan after living in Norway for 10 years, I asked my aunts for it, but they didn’t remember it at all.”

Umar’s grandmother had passed on while he was away, and according to tradition, all her belongings had been given to poor people. “I was just weeping,” remembers Umar. In 2017, he went to the market in Omdurman — a magical place where one used to be able to find just about anything — and talked to vendors for a year, asking for this specific garment, for any price.

Therahat is a skirt made of leather, grass and straw strings, beaded by Ahmed Umar.

Photo by Jakob H Svensen.

Meanwhile, he collected beads around the world, in New York, Cairo and Sudan, until one day, he saw an edge of a rahat, a skirt made of leather, grass and straw strings, peaking out of a bag at Omdurman market. The vendor made him buy the whole outfit, he couldn’t just get the skirt alone, for an exorbitant amount of Sudanese pounds. Umar started beading it according to his memories of his grandmother and with the help of old videos.

The next step, which took him four years, was to find a woman who’d be willing to teach him. “At some point my friends told me to just give up,” he says. The many ladies he asked for help didn’t dare ask their friends, fearing that it would bring a negative association to them.

Until he spoke with Cairo-based Sudanese musician Asia Madani who casually mentioned that she could teach him. “I said, ‘If you’re serious, I’ll take a plane and come to Cairo right now,’” Umar laughs. He went to Egypt and together, they began curating songs from different parts of Sudan, describing the different stages of courtship and a wedding, giving praise to the bride’s family and the bride herself.

“Brides usually learn the dance in three months, but I’m a 30-something year old man and my body is like a stick, so I took three years,” says Umar, describing the difficulties of being taught movements that were not designed for his body type. “I thought I’m good at dancing and I can move my shoulders, but those hips are big liars.” For authenticity purposes, Umar increased his chocolate intake to increase his body’s curves.

Talitin (Arabic for third) is Ahmed Umar’s performance at the Venice Biennale.

Photo by Jakob H Svensen.

When the Biennale invited Umar to showcase his art, he initially wanted to exhibit a different project, one that he was confident about. But they requested the bridal dance, which Umar accepted as a sort of destiny. “I dare talk about a lot of things through my art, but dancing in front of people half naked and having this responsibility of showing a tradition of which there’s no proper documentation was just nerve-wrecking,” he says.

The audience’s reception was outstanding, though different than he expected. “For me, dancing is about joy and happiness, but some of the non-Sudanese people sometimes react with tears,” he shares. “Sudanese people cheer and jump, but when I take it out of its original context, it becomes a performance, an art piece that they [non-Sudanese] are not a part of.”

Umar is the second Sudanese artist to show at the Venice Biennale, the first Sudanese artist to show at the Biennale of Sydney. His presence as a Sudanese gay man carries twofold significance, especially at a time when Sudan is suffering the world’s most severe internal displacement crisis amidst a war that is often referred to as “forgotten.”

Ahmed Umar is set to exhibit at Art Basel in June 2024.

Photo by Jaqculine Landvik.

“I think that the world does not sympathize with us, because they don’t know us,” says Umar. “We’re hiding all these beautiful things that make us us by showing this identity-less image of ourselves as Sudanese, hiding behind being Arabs and Muslims.”

Through his art, Umar works towards preserving Sudanese traditions and modernizing them to fit contemporary context, to find pride and joy in our multiplicity. Returning to Oslo from Venice, he immediately starts preparing his next showcase at Art Basel, writing himself, a queer artist, into Sudanese art history.

- Cameroon's Pavilion Brings the first NFT Art Show to the Venice Biennale ›

- The African Countries Showing at the 2024 Venice Biennale ›

- At the 60th Venice Biennale, Wael Shawky Invites Us to Reflect on Past Fictions and Myths ›

- What It’s Like To…Revive the Art of Egyptian Cabaret in New York City | OkayAfrica ›