How A New Generation of Comic Book Creators is Sharing Africa’s History

From Uganda to the DRC, Nigeria to Côte d'Ivoire, comic book creators and graphic novel illustrators are taking full advantage of the art-form to tell uniquely African stories.

For many outside of the continent, Captain Africa, with his solar-powered cape enabling him to fly at super-speed, was the first African superhero comic to go global. Created by Ghanaian Andy Akman and published by Nigeria's African Comics Limited, Captain Africa spent the late '80s on a mission to "fight the evil and dark forces that threatened Africa and the whole world," particularly in a post-colonial world.

While the comic book series as it was originally known may have sputtered out, the influence of Captain Africa lives on, in a new generation of comic book creators and graphic novelists who're using the art-form to engage readers with various parts of the continent's history. In illustrating their own brands of African superheroes and everyman characters, they're envisioning a future of Africa wholly anchored in its past.

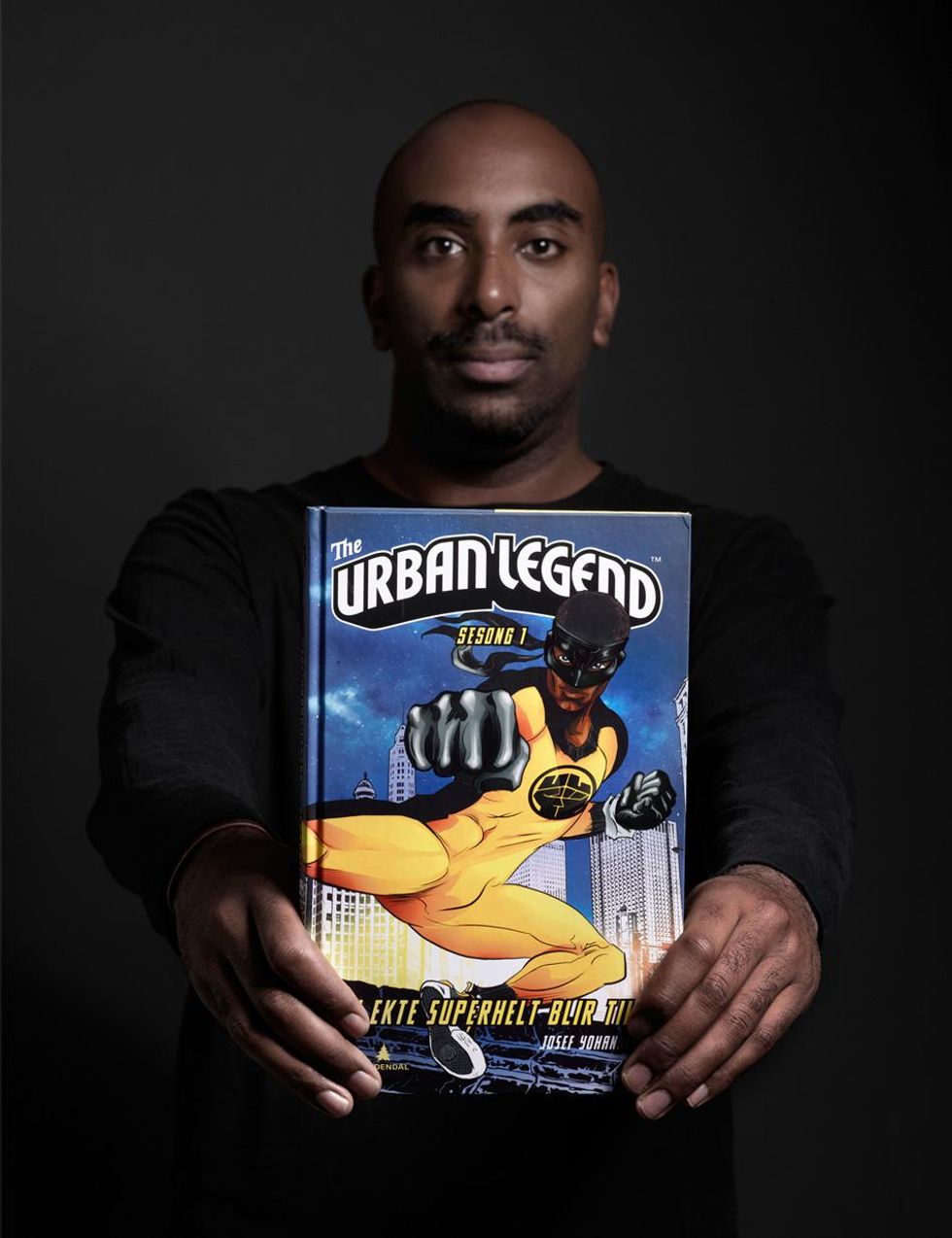

Much of what drove Akman to create Captain Africa is what drives many creators today — the desire to tell African stories without the white savior lens. Rallying against the typical views held at the time that African comic book characters were unsophisticated and in need of saving, Akman's Captain Africa was a successful businessman when he wasn't fighting crime. Similarly, Eritrean-Norwegian comic book artist and writer Josef Yohannes' The Urban Legend is a school teacher who adopts his alter-ego after the murder of his cousin.

Yohannes, who published the first issue of The Urban Legend in 2012, looked to history — both personal and public — for his superhero's moniker. "The name was very important and played an essential part in who he was and what he stands for," he told OkayAfrica. "So I named him Malcolm Tzegai Madiba. I named him after Malcolm X, my father Tzegai (which is also my middle name) and Nelson Mandela. I wanted my superhero to be named after people who fought so hard for justice and equality, and that gave the voiceless a voice and stood for people who couldn't stand up for themselves. I also wanted the name to symbolize power, strength and unity."

Yohannes also uses history to inform the stories he tells that are rooted in current social ills, like bullying, climate change, and police brutality against Black people. "I realized the power in comics when I saw the influence The Urban Legend had on kids, across genders, religions, cultures and ethnicities," he says. "Traveling all around the world with my superhero, I saw what a powerful impact it had on these kids, especially kids in Africa who had never seen a Black superhero before. I used to read a lot of comic books when I was a kid, but read less and less the older I got."

Elupe Comics, based in Kampala, Uganda, started in 2016 by Ssentongo Charles, was also created to help make young Africans more interested in their own history. "The vision was inspired due to the realization of the deterioration of interest in our native culture and norms in the current youth," the Elupe team told OkayAfrica.

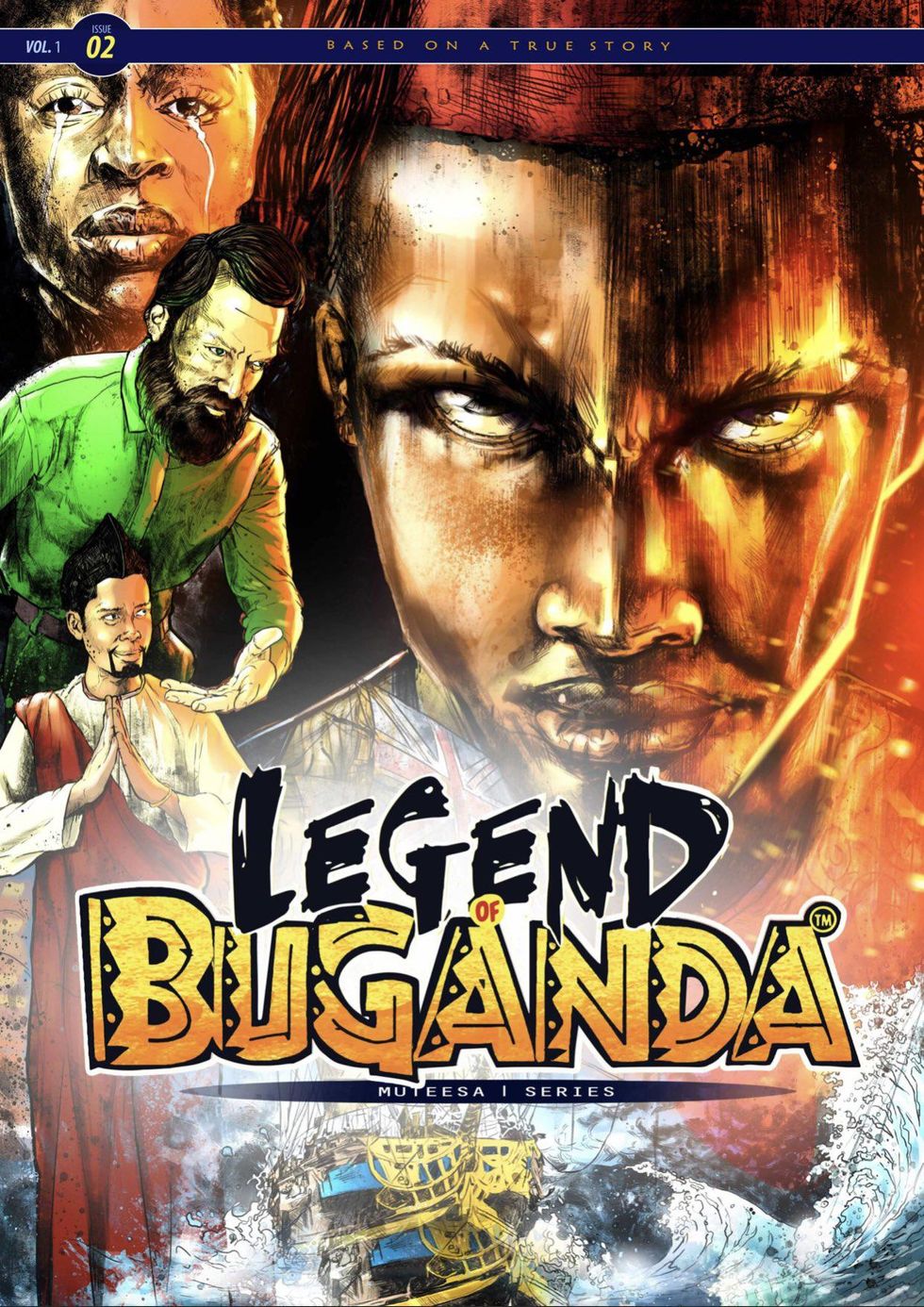

Among the titles they've worked on so far include The Ganda and Legend of Buganda, which is a manga-style comic series based on the history of Buganda; the largest of Uganda's recognized traditional kingdoms. It's the brainchild of Her Royal Highness Princess Joan Nassolo Tebatagwabwe, the eldest daughter of Buganda's current king, Kabaka Ronald Muwenda Mutebi. She wrote the first volume, which chronicles the reign of Kabaka Muteesa I in the mid-19th century, when Arab traders and European colonizers first entered the nation, in the hopes of stimulating engagement with Buganda's heritage among the kingdom's youth. She also translated the stories into manga, to extend the history beyond Uganda's borders.

Elupe's tagline for the series is 'Knowing your history gives direction in shaping your future.' As Tebatagwabwe said in an interview, the idea came to her while she was reading a manga comic. "The one I was reading at the time was historical, and I was very impressed with the way it was presented, as well as how the information was broken down with the use of imagery and symbols, not so much written out in words," she said. She thought the form would be well-suited to share Bugandan heritage too.

"Not everyone reads history books today. A lot of people prefer taking in information visually - comics, drawings, paintings, animations, illustrations, films etc. In the recognition that culture is dynamic, Buganda also needs to move with the times when appropriate, and find innovative and engaging ways of preserving our history, culture and heritage," she added, mixing a few fictional elements into the stories.

Congolese cartoonist Barly Baruti, who illustrated the historical fiction story of adventure and friendship set against the backdrop of World War I, titled Madame Livingstone, echoes Tebatagwabwe. Madame Livingstone was published with writer Christophe Cassiau-Haurie earlier this year, and Baruti believes in the "limitless possibilities of the art-form to express emotions, feelings, space. We breathe, we fly, we touch the clouds," he told OkayAfrica.

There is so much that can be done with the visual storytelling aspect of comic books, adds Beserat Debebe from Ethiopia's Etan Comics, whose newest release, Zufan, fictionalizes Italy's invasion of Ethiopia in a narrative fit for the whole family. "Not only do they allow us to tell different genres of African stories through colorful and vivid visuals, they also allow us to tell them using African art styles, languages and letters," he says. "For example, we publish our books in Amharic. Our sound effects are not just POW, BOOM, etc. They are tailored to our sounds and rhythms. Just like manga, we have our own art style. We even have our own term for comics: 'sensi'ils,' a term that translates to 'chained art' or 'sequential art'." These are unique elements of Ethiopian heritage that can be shared through comics, a more affordable method of expression than making animation movies, TV shows or live action films.

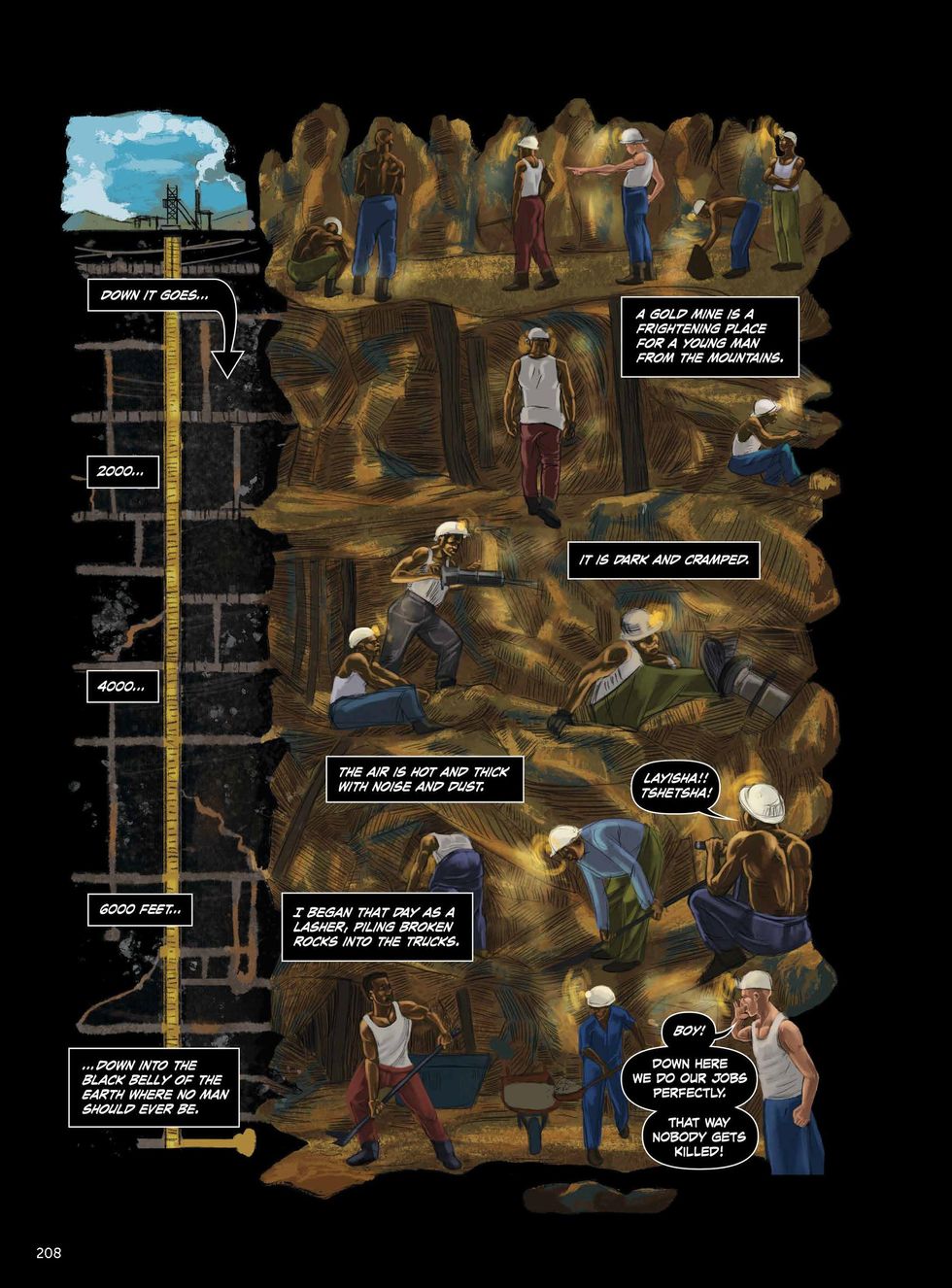

Sometimes the continent's history can be too traumatizing to revisit directly, especially for a younger audience. It becomes more digestible in comic book or graphic novel form. "It invites constructive discussion and healing," Debebe told OkayAfrica. Indeed, the upcoming graphic novel series All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa, due in April 2022, is a graphic novel of six true stories of resistance by marginalized South Africans against the country's colonial government in the years leading up to apartheid. Each of the stories is illustrated by a different South African artist. "Comics cross all class lines; rich and poor people and everyone in between love comic books," says André Trantraal, one of the series' illustrators. "In Africa, it is important that we use a medium with this type of universal appeal to get people to love books and to love stories, and maybe even inspire them to tell their own."

Adds fellow illustrator, Tumi Mamabolo: "A graphic history such as All Rise makes important historical figures and events more accessible to the wider public. Students, for example, will find more engagement in these stories than if they were simply put in a textbook. The beautiful thing about this graphic novel is that, in appealing to a broader audience, the real men and women depicted within get the recognition they deserve and aren't lost to history."

Perhaps this is the most exciting aspect that the comic book art-form holds for African history: the chance to affirm the multi-dimensionality of Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. "Our past is not all about slavery," says Debebe. "African history is one of the oldest and richest histories in the world. We have stories about ancient civilizations, stories of honor, courage, too."

Writers like Ivorian Marguerite Abouet have been long been passionate about doing this. Abouet's Aya of Yop City, which was made with illustrator Clement Oubrerie, follows the daily lives of Aya, her family and friends and the members of her community in the '70s. This graphic novel was created due to the author's desire to show a different view of Africa besides the poverty and war mostly shown in mainstream media. It was turned into an animated film in 2012.

All of these stories allow for what president of African Comics Limited and publisher of Captain Africa, Mbadiwe Emelumba spoke of in an interview with the NY Times in 1988. "We have our own culture, our own heritage," he said. "It's important to defend against cultural colonialism." Or as Christophe Cassiau-Haurie puts it, "Africans are tired of being looked at with commiseration."

With today's crop of creators and illustrators, that desire seems more fervent than ever.

- Nnedi Okorafor Is Dropping a 5-Issue Comic Inspired By Legendary ... ›

- Marvel's First Nigerian Superhero, Penned by Nnedi Okorafor, Is ... ›

- 5 African Superheroes You Need To Know - OkayAfrica ›

- This is How Zambian Words and Accents Made Their Way Into ... ›

- Africa's First Marvel Superhero Makes His Cinematic Debut In ... ›

- You Need To See the Stunning Covers of This Afro-Brazilian Comic ... ›

- This Pre-Colonial African Warrior Queen is Your Next Favorite ... ›

- Breaking Down the First Trailer of “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” - OkayAfrica ›

- ‘Yasuke: Way of the Butterfly’ Tells the Origin Story of a Real-Life African Samurai - Okayplayer ›