Meet the Shortlisted Writers for the 2021 AKO Caine Prize

Get acquainted with the five writers shortlisted for this year's AKO Caine Prize, one of the most prestigious African literature accolades.

The 2021 AKO Caine Prize has recently announced this year's shortlisted writers for, perhaps, one of the most coveted African Literature awards on the continent. This year, the AKO Caine Prize celebrates 21 years of highlighting literary talent across Africa.

Five writers, hailing from Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia and Namibia, made this year's shortlist, with the winner set to be announced later in the year. The shortlist comprises Rémy Ngamije, Doreen Baingana, Troy Onyango, Iryn Tushabe and Meron Hadero.

Describing this year's cohort of writers, Founding Director of the African Writers Trust and this year's chair of judges, Goretti Kyomuhendo enthused:

"What comes across vividly in this year's shortlisted stories, through their impressive craft and intelligent language is their ability to resonate profoundly with the reader. My fellow judges and I were reminded, once again, of the redemptive power of stories. These remarkable five narratives all exemplify, with delicacy and truth, what good fiction is. Intermingling politics and humour, brutality and love, loss and hope, each of these stories poignantly convey images of the continent and its diaspora that demand to be read. The true art of African storytelling is manifested in the voices of these five exceptional pieces."

We caught up with each of the five writers, and they indulged us in their respective writing processes, personal quirks and what the AKO Caine Prize means to them.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

READ: Irenosen Okojie Wins This Year's Prestigious AKO Caine Prize

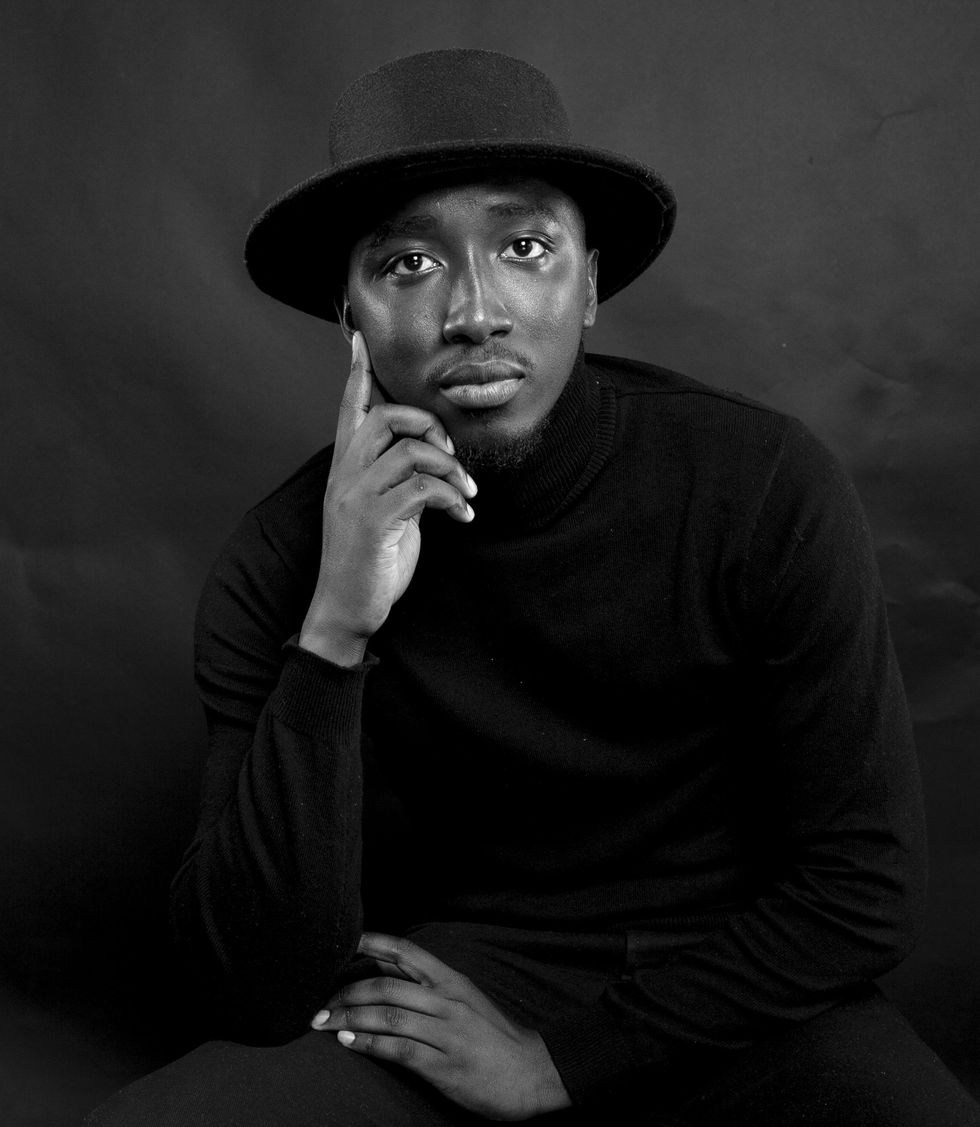

Rémy Ngamije

Photo by Abantu Book Festival

Rémy Ngamije is a Rwandan-born Namibian writer and the editor-in-chief of Namibia's first literary magazine Doek!. His work has been featured in a number of publications including Litro Magazine, AFREADA, The Johannesburg Review of Books and The Kalahari Review, among several others. He was shortlisted for the 2020 AKO Caine Prize and is this year's regional winner for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. His recently shortlisted story The Giver of Nicknames was published in Lolwe in 2020.

What inspired the short story The Giver of Nicknames?

Teenagehood yields some of the most interesting stories around. Perhaps because of hormonal changes, the search for self-hood, the pressures of future life or the constant presence of the past. Either way, stories set in a character's teenage years provide an opportunity to explore humanity at the hot crust of ongoing development. The Giver of Nicknames was inspired by the desire to write a short story akin to seeing lava on the ocean floor before it hardens and cools down to become the Earth's crust.

What advice has helped you write more compelling stories?

Peter Orner, a friend and mentor, once said: "Carry on." And James Baldwin, a writer I admire, has very good advice too: "Good luck!"

What three books/stories/pieces of writing have stayed with you since reading them?

Samarkand by Amin Maalouf, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy and A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James are books I go back to many times.

Which author, living or dead, would you like to co-author a story with?

J. R. R Tolkien and James Baldwin.

Is there anything quirky or unusual that you do during the writing process?

I try my utmost best not to be distracted by music. No writing process can resist Sauti Sol or Missy Elliot's gravitational pull.

What does being shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize, yet again, mean to you?

I am delighted to be representing Lolwe, a pioneering literary magazine with its roots, struggles and hopes firmly dug into the African continent. That, for me, is what it means to win: being a part of a continental literary magazine committed to publishing and rewarding African writers on the continent and the diaspora.

Iryn Tushabe

Photo by Robin Schlaht.

Iryn Tushabe is a Canadian-based Ugandan writer whose work has been featured in Briarpatch Magazine, Adda, and Prairies North, among several other publications. Tushabe is currently working on her debut novel Everything is Fine Here. Her shortlisted story, A Separation, was published in EXILE Quarterly in 2018.

What inspired the short story A Separation?

I wrote it back in 2015, during a period when I couldn't work in Canada due to work permit delays. I had also always wanted to write creatively. Unfortunately, my grandmother had died a few months earlier and I was reeling from that. I think that's what the story is about — losing someone close to you.

What advice has helped you write more compelling stories?

Write everyday. A mentor of mine, Canadian writer Alissa York, taught me that during a writing programme in 2018. Writing is a discipline, and if you just wait for your muse in order to write, it takes forever. Writing everyday, no matter how it turns out, even if it's garbage, reminds me that nothing ever really goes to waste. I have two kids right now so it's hard. Buteveryday, I make an effort to sit in front of my computer to think something through. What matters, at the end of the day, is that I thought about what I wanted to do. The story percolates at the back of your mind, so there's work being done even when you don't know.

What three books/stories/pieces of writing have stayed with you since reading them?

Canadian writer Miriam Toews writes from a place of having grown up in a strict religion. I have read all her books and more recently, Women Talking. It's very important work — just the humanity and grace she gives her characters in difficult situations and how she deals with the translation aspect of her work.

Helen Oyeyemi's The Icarus Girl. I think it's simply ingenious to be able to write about a main character who's that young, but her point of view is just so alive and adultlike, and she's battling difficult situations. Generally, I adore stories about children and teenagers.

Leila Aboulela's Lyrics Alley had a huge impact on me. I read it at a time when I was deciding that I wanted to become a writer of fiction and creative non-fiction. I adored how she brought all the places to life because the characters move from Sudan to Egypt.

I know you asked for three but I have to mention Dinaw Mengestu! All Our Names is partially set in Uganda and the United States. His female characters are wonderfully written. It's hard to find men who can write female characters who are intelligent, 3D and well-rounded.

Which author, living or dead, would you like to co-author a story with?

Helen Oyeyemi, hands down! She writes wonderfully weird stories. She takes folktales and turns them on their head — I have no idea how she does that! I'd definitely love to be in her process and see how she creates her characters and the worlds that she takes them to. She's definitely one I'd love to meet.

Is there anything quirky or unusual that you do during the writing process?

I'm so vanilla when it comes to writing! I wish I had some cool things that I did, but writing when you have kids is hard because they essentially decide your schedule. Now that the kids are home-schooling because of the pandemic, that has forced me to change my schedule altogether. I always take my notebook along and write wherever and whenever — even from the bleachers when my child is playing basketball.

What does it mean, to you, to have been shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize?

It was such a joy to be shortlisted this year. I write and publish in Canada but my stories are always about home, set in Uganda. For my work to be read by an African audience, because that's who I write for, is meaningful to me. Beyond winning, the shortlisting is wonderful in itself because it will expose my writing to the African audience. I'm working on a novel right now. I'm hoping that once they get to know me, and should they like the story, they'll also want to read the novel. At its core, this short story is about death, a very difficult subject. It's a subject that's near and dear to my heart — I wrote it when I was thinking about my grandmother. And so, I'm really grateful to that story because it's taken me places.

Troy Onyango

Photo by Oduor Jagero.

Troy Onyango is a Kenyan writer and the founder and editor-in-chief of Lolwe. His work has been featured in a variety of publications including Prairie Schooner, Wasafari, Johannesburg Review of Books, Nairobi Noir and several others. He has won the inaugural Nyanza Literary Festival Prize and has been shortlisted for several literature awards including the Short Story Day Africa Prize and the Brittle Paper Awards. His recently shortlisted story This Little Light of Mine was published in Doek! in 2020.

What inspired the short story This Little Light of Mine?

I was just curious about how people navigate dating apps in the 21st century, and the kind of loneliness that comes with that exploration — especially in a city like Nairobi. And what happens if you are not part of what is considered the ideal pool or you don't fit into the conventional beauty standards. I remember having a conversation with a friend, who is living with a disability a while ago, and he was telling me how difficult it was to navigate the dating scene in his condition. I guess that's the loneliness I wanted to explore.

What advice has helped you write more compelling stories?

I think there are two. The first one was advice I was given when I was still young in my writing career. Someone said: "Read, read then write." And as simple as it is, it has continued to shape my writing in a way that I'm grateful for. The second one is an essay by Daniel Older that I stumbled upon. There's this line that says: "Writing begins with forgiveness." You have to forgive yourself, you know, on the bad days when you can't put anything down. It's just shaped a lot of how I think about writing and now I don't beat myself up about sentences not being perfect or the story not coming together as it should.

What three books/stories/pieces of writing have stayed with you since reading them?

The first one would be Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon. I've just not been able to shake it off. It has influenced my imagination and a lot of how I think about things even in my personal life, away from the writing.

The second one would be the God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy. It's a brilliant book and something I recommend to everyone. Whenever I think of a perfect novel, I think of the God of Small Things. It has shaped me retrospectively.

Summer Lightning & Other Stories by Jamaican writer, Olive Senior. It's a small short story collection, but currently the most influential book in my life. Lastly, The Book of Night Women by Marlon James. The language, and everything in it, is so explosive. I adore his work!

Which author, living or dead, would you like to co-author a story with?

As the founder and editor-in-chief of Lolwe, I get to collaborate with so many brilliant writers on the continent. I mean, every writer I've worked with on Lolwe has been a joy. Some of them are young, while some have been writing for a long time. For some, these are their first-ever stories!

Is there anything quirky or unusual that you do during the writing process?

I don't write my stories unless I have a title. You know, there's this saying in my language: "To name something is to give it life" and I always tend to bring that into my work. Whenever I'm working on something, the name might change later, but I always start with a title. Some people find it really strange. I don't know how common it is, but that's just something that has become part of my writing routine.

What does it mean, to you, to have been shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize?

Just the shortlisting alone is a win, even if I don't get to win the prize eventually. For one, it's a short story published in an African publication. I can't even call Doek! small anymore because it's grown so much. My story being in an African publication, and being accessible to anyone, validates the fact that the work is being done. There are all these amazing platforms coming out and they're taking craft and tutorial processes seriously. They're bringing out quality work.

Meron Hadero

Photo supplied by Meron Hadero

An American-based Ethiopian writer, Meron Hadero's work has been featured in The Iowa Review, The Missouri Review, New England Review, Best American Short Stories, among others. Her Story, The Wall, was shortlisted for the 2019 AKO Caine Prize while her most recent shortlisting is for The Street Sweep, published in ZYZZYVA in 2018.

What inspired the short story The Street Sweep?

The Street Sweep is part of my forthcoming collection of stories focusing on immigrants, refugees and those facing displacement. One starting point came from the urgency of the main character's situation as his family is on the verge of losing their home. That threat of displacement hangs over him as he sets out on what he's told is an impossible challenge, one where he is tested and where he tests his world too.

What advice has helped you write more compelling stories?

The best advice I ever got was that first drafts are often not that great, which is another way of saying this process takes work and time. Understanding how important (and long, and iterative) the revision process can be, helped me keep faith in certain pieces that took a while to come together.

What three books/stories/pieces of writing have stayed with you since reading them?

There are so many, but the first to spring to mind is Dinaw Mengestu's The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears. I admired that, though he wrote in broad strokes about the Derg in Ethiopia, the gravity of that history was sensed nonetheless, just as a black hole is intuited by observing the bend of the light around it and not the darkness itself.

And then there's Maaza Mengiste's Beneath the Lion's Gaze, which takes a close and unflinching look at the Derg, haunting the reader, as one imagines it haunts her characters too.

Another is Lesley Nneka Arimah's What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky. She transports the reader by the sheer force of her creativity, and that stayed with me, just like any great journey would.

Which author, living or dead, would you like to co-author a story with?

Someone like Italo Calvino. Creatively, I'd love to think through the complex challenges we face in the world today, alongside a writer with an unfettered imagination and the capacity to experiment, reinvent, and expand what storytelling itself can do — both for literature and for this collective moment.

Is there anything quirky or unusual that you do during the writing process?

The most unusual thing I do during my writing process is watching, or reading, mysteries to take my mind off a project — and to help me put aside my own creative puzzles.

What does it mean, to you, to have been shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize?

It's an incredible honour and I'm thrilled that my story has this opportunity to potentially connect with new readers. I'm also excited that new audiences might discover ZYZZYVA, the wonderful magazine that published it. I also look forward to getting to know this incredible cohort and their writing. As for the possibility of winning, I can genuinely say that being shortlisted is as immensely meaningful, to me, as winning would be.

Doreen Baingana

Photo by Jérémy Baron.

Doreen Baingana's collection of short stories Tropical Fish was awarded both the Grace Paley Prize for Short Fiction and the Commonwealth Prize for Best First Book, Africa Region. Two of the Ugandan writer's short stories have previously been shortlisted for the 2004 and 2005 AKO Caine Prize. She is also the co-founder of the Mawazo Africa Writing Institute based in Entebbe, Uganda. Lucky, her most recently shortlisted story, was published in the Ibua Journal in 2021.

What inspired the short story Lucky?

A friend told me how they got stuck at school during the civil war in the late 1980s and the Lakwena Army ran through the school. I wanted to explore why Uganda is so violent. We're many things, including being friendly people, but why this violent history and violent present? Perhaps it's what we keep passing on, from generation to generation. I've also been writing a novel based on Alice Lakwena for the past few years and wanted to include what I'd call innocent bystanders, people who were affected by war even though they were not direct participants. I have several voices or perspectives — and this story was one of them — but it also worked as a standalone.

What advice has helped you write more compelling stories?

I have no idea where I read this, but it was a long time ago: "We're not providing answers, we are exploring questions." It just resonated in terms of the way I do my own work. I don't have to solve something in my fiction. It's just about opening up a space for exploration and wonder.

What three books/stories/pieces of writing have stayed with you since reading them?

Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter. I was so moved by her exploration of a young girl trying to find herself — and how she weaved the personal and political in such a wonderful, eloquent and lyrical way. And then there's Toni Morrison's Beloved. Again, a story that weaves the personal and political lyrical language so piercingly. She made anyone who reads it enter that history of trauma. It's just immensely powerful.

I think One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Marquez. I'm bringing up all the standards because these are great books. I'd like to add a book from Ugandan writer, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi. She's just published a book called A Girl is a Body of Water (UK title: First Woman). I love how she so audaciously and unabashedly uses Ugandan English. She writes Ugandan stories with no apology, and it made me realise how, when we read, we are taking a leap into some foreign world.

Which author, living or dead, would you like to co-author a story with?

The most wonderful thing I like about writing is that I don't co-author — it is solitary work. It is work I do on my own. I'm doing more collaboration now because I've moved into theatre. As a script writer you work with the whole team before the final product. But I like the fact that I, as a writer, don't have to work with anybody except the editors and maybe the readers. For me, writing is an act of finding my voice.

Is there anything quirky or unusual that you do during the writing process?

I don't know if it's quirky or unusual because I don't know how other people do it. I like playing jazz in the background. Actually, I like playing any kind of music that's suited for the background because it keeps my mind focused. I don't start thinking about the bills that need to be paid or the stranger who was rude to me. Although I talked about writing as solitary work, it makes me feel less alone. There's something about jazz that I think also helps with the writing itself. It has its own formulas but not as neat — it moves from here to there. I love that.

What does it mean, to you, to have been shortlisted for the AKO Caine Prize?

I am about to finish my novel and send it out, so it's an affirmation to keep going, firstly. For me, the teaching of creative writing goes hand-in-hand with my life's mission. Hopefully, it will bring attention to my organisation, the Mawazo Africa Writing Institute, which aims to enhance the teaching of creative writing across Africa.

- Kenyan Author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o Nominated for 2021 Booker Prize ... ›

- Commonwealth Short Story Prize Announces 2021 Shortlist ... ›

- Irenosen Okojie Wins 2020 Prestigious AKO Caine Prize - OkayAfrica ›

- The Prestigious AKO Caine Prize Announces 2020 Shortlist of ... ›

- Nigerian Writer Lesley Nneka Arimah is the 2019 Winner of the ... ›

- Who Should Win the 2018 Caine Prize for African Writing ... ›

- Caine Prize Preview 2017: Who Will Greet You When You Get ... ›