The Root of the Issue: The Politics of Black Women's Hair

Discussing the politics and problematics of the "You Can Touch My Hair" exhibit, black women's hair and the natural hair movement

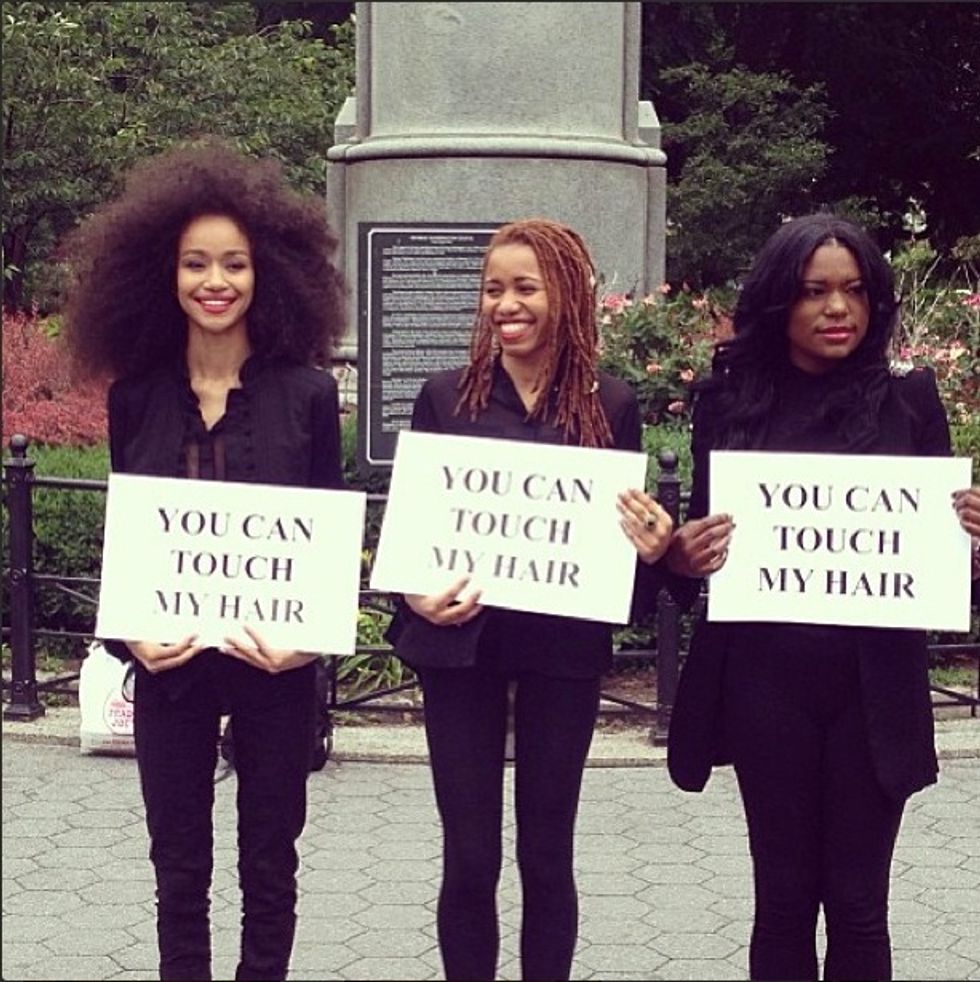

The internet has been up in arms about the 'You Can Touch My Hair' exhibit held at Union Square in NYC, which was organised by Antonia Opiah, founder of natural hair blog un-ruly.com. The two-day event involved several models holding up signs that read 'You Can Touch My Hair' (and, on the second day, women holding 'You Can't Touch My Hair' signs in protest). On June 7th, The Sanaa Circle, a group affiliated with the National Museum of African Art, presented a panel and discussion at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. The panel took on questions of health and beauty surrounding contemporary black women's hair. The issue was grounded in the heritage and history of Africa, with historians, medical professionals, models, and a curator presenting the discussion.

A group of us came together to discuss the politics of black women's hair in these two events, and the greater national and global conversations about othering blackness, femininity, and the perils of nonblack 'curiosity'.

ZEPHYR: Part of my hesitance to commit thoughts to paper came from my initial thought about the "You Can Touch My Hair" event: that it was mind-numbingly silly. I wasn't sure how to formulate cohesive thoughts on the whole thing...but its a necessary conversation, and one I'd like to contribute to at least in a small way.

MARYAM: There's a contrast to the National Museum of African Art discussion and the 'Can I Touch Your Hair' exhibit that basically speaks to my feelings on both. The panel discussion is interesting in that it recognizes a history then seeks to discuss it and problematize it. I don't see it as different from art expressions that have represented fashion/politics and overall cultural understandings of 'dress' which hair is in many ways.

A Regional Walk Through The History of African Hair Braiding

From West African Fulani braids to Southern Africa’s Bantu Knots, we explore Africa’s rich history and connection to hair braiding.

AYANA: I appreciated the 'Health, Hair and Heritage' panel's attempts to at least situate their conversation historically. It definitely makes sense to have that discussion in a museum where questions about aesthetics, politics, history and authenticity are primary concerns.

DERICA: When you're dealing with the subject of black hair, you're also taking on the issue of U.S. society's attitude to black women more broadly and that's a minefield of racialised + gendered power dynamics. Like both Ayana and Maryam, I'm here for discussions and art-making that situate hair within specific social and cultural contexts: and that can be in a museum or on the street. But this 'You Can Touch My Hair' piece is not the one, given what I've read in Opiah's Huff Po article, the twitter responses, and seen in this video

[embed width="715"][/embed]

MARYAM: As for the 'You Can Touch My Hair' ish, I'm just not about it. I saw a lot of women tweeting from the exhibit mentioning having rich discussions during the exhibit so I guess that's productive, but what makes the exhibit particularly hard to mess with is Opiah's HuffPo article. Neither the argument nor the exhibit seems to be problematizing the 'otherness' of black hair or the curiosity. It just read as though she was trying to justify exoticism, which I didn't know we were trying to justify at all (smh at her dismissal of how asking to touch black people's hair is about the ownership of black bodies). If I'm not mistaken, history strongly suggests that we need to stop indulging white curiosity and trying to placate it no?

ZEPHYR: Clearly, the impetus behind such an event is not to interrogate these very important questions of body ownership, race, gender, and permission, as it seems the Smithsonian panel is at least attempting to do. Like Maryam, it read to me much more as a way to depoliticize a “hot topic" issue in order to make it accessible to white people. What strikes me most here, though, is the illogical thinking that allows someone to create an event like this, while insisting "there's nothing political here! it's just hair/curiosity!" Does the author not realize that without the race and gender politics at play here, there wouldn't even BE a "natural hair movement" or anything of the sort? It's there, whether she or anyone else wants to acknowledge it.

AYANA: Reading the article was a cringe-worthy experience. It was as though Opiah wants to invite the fetishization of black hair by nonblacks, while shaming (or at the very least dismissing out of hand) the blacks (and nonblacks) who feel immediately uncomfortable about the idea. Her reductive “research" came to a dangerous conclusion (it's not about a black woman's hair, it's just “curiosity" about “strangers"). At the end, Opiah stages what she calls a “loaded call to action" around hair that worries me because it also presumes equality in/around friendship. Basically, if you're curious about black hair and have a black friend (or someone you think is a friend) it should be fine to ask them to give in to your voyeuristic desire?

DERICA: Rather than engaging thoughtfully with those issues, I see an attempt to shirk them by making “curiosity" the buzzword: “ohhh, white people are just curious!" “nonblack people just fascinated by difference!" That said, I understand that one justification for this exhibit/performance is to allow black women to take back agency by preempting the invasive touch with the “You Can Touch My hair" sign. But I'd have liked the whole thing to challenge the power-dynamic even further. Something along the lines of: “You Can Touch My Hair, but then I get to touch you .... anywhere".

ZEPHYR: I also understand the attempt to create some semblance of agency for the black women participating by holding up the signs, but it seems to me the onus is once again being placed on black women having to justify their physical existence in response to white curiosity. It is never the other way around—why is no one asking why white people need to touch our hair so bad to begin with? Where's the political interrogation on that side? Maybe if it this wasn't one-sided, I could begin to be okay with it…but that's rarely been the case.

DERICA: I also think Opiah's out of hand dismissal of the argument that a sense of “white ownership" of black people might still pervade interracial interactions, denotes a failure on her part to properly engage with the history of the United States. Let's be real: as recently 150 years ago, black people in America had their heads forcibly shaved and were put on auction blocks where their bodies could be touched, tugged and prodded without permission. The legacy of that system and those actions takes some real working out.

ZEPHYR: This exhibit follows the age-old American tradition (not that we've been the first or last to do it) of re-writing history without its troublesome contexts to make things easier for white audiences to swallow. I can't be the only one who is sick of black history being reduced to sterile, uncontroversial "let's all just get along!"-type clips so that audiences won't be made uncomfortable. But without that history, the conversation doesn't actually exist, so what is the real point?

The other thing it does is assume that these conversations are not already taking place when they are, all the time, in communities around the country and the world. I think if nonblack people want to be involved in this "politics of hair" conversation—and I think everyone should, not just black women—they should be willing to acknowledge the legacy of race and gender power at the core here, and start from there. Without that, the 'Can I Touch Your Hair' event to me is nothing more than another instance of placating white desire to be down with black culture when its trendy to do so, without doing any of the real thought or work required to make that participation meaningful.

Like Paul Mooney said, "Everybody wants to be a nigger, but nobody wants to be a nigger." I'll leave with that.

- The Hidden World Of Harlem's African Braiders - OkayAfrica ›

- Natural Beauties Share Why CURLFEST 2018 Is More Than Just a ... ›

- Our Favorite Natural Hair Gurus Share Tips on How to Keep Curls ... ›

- This Photo of Michelle Obama Rocking Her Natural Hair on Vacation ... ›

- This Black Hairstyle Collective Is Embracing the Beauty of Natural ... ›

- Zozibini Tunzi Slams Racist Hair Advert - OkayAfrica ›

- Women's History Museum's 'Leading Ladies' Podcast Returns for Second Season - OkayAfrica ›

- Zulaikha Patel Celebrates Black Hair With New Book 'My Coily Crowny Hair' - OkayAfrica ›

- 'The Hair Appointment' Is a Gorgeous Photo Series Showing the Beauty of Black Hairstyling - Okayplayer ›