Maboneng: A Place And Its Lights

South Africa-based writer and photographer Tseliso Monaheng lived in The Maboneng Precinct for seven years, and documented its transformation from a creative hub to its current state where hardly any art galleries remain and the food culture has been decimated.

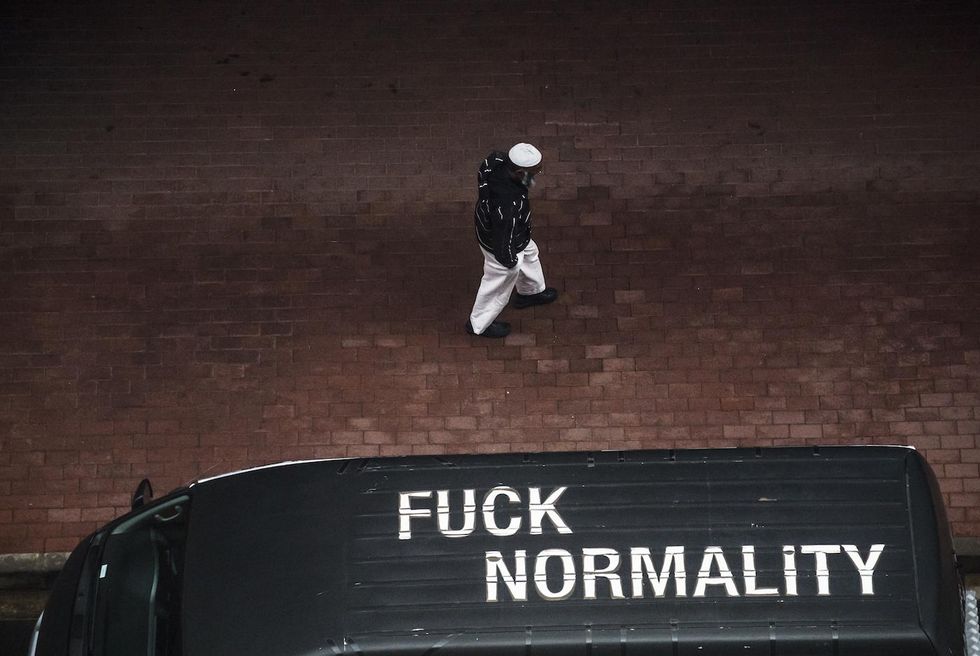

The Maboneng Precinct is an outlier, a prop, a found object dumped in the middle of Jeppestown. This is one version of the story—the simple take, the viral tweet, the meme-able moment, the click-bait.

It would require one to believe that the rest of inner city Joburg is integrated in order for this "Maboneng-as-outlier" assertion to hold weight. The architectural makeup of this city, comprising mostly empty silos arching aimlessly towards the sky, suggests that Maboneng isn't an outlier, but a piece of the puzzle that is Joburg; by design, a city that supports parallel existences within a relatively small area. Blame Apartheid and spatial planning, not the now-liquidated Propertuity development company.

Arrival

I moved here a little over seven years ago.

Here is the stretch of Fox Street that is barricaded by the Jeppestown train station towards the East, and the M31 highway towards the West.

Maboneng has been the playground for simplistic, binary interpretations of space and its place in society. On one side are those who've lauded it as a "welcome addition" to the city, and a tributary transporting people who wish to "take back the city".

The glaring question becomes: Which people are being spoken to/about? Are these the same people who've been living in the area many decades prior to the existence of Maboneng as a living space? Surely it's not the corner store owner who's been around since his father ran the business in the late eighties; or the herbsmen and the women chefs who've made a home at Kwa Mai-Mai; or my own grandmother whom, according to my aunt, would travel from Soweto to come and work in Jeppestown's factories in her heyday?

On the other extreme are the social justice warriors who've made Maboneng a talking point over conversations at dinner tables. To them, the area's developers are ill-intentioned rogue capitalists who care for nothing but the bottom line. Which they are, really.

But these clear-cut, good/bad categorisations gloss over a lot of things; like how spaces change over time, and how the make-up of any one place follows those strictures and paths of transformation.

Ghost Town

I have seen the precinct shift and bend to accommodate the demands of its environment, and have also witnessed how the effects of developers who lie perpetually have stunted the original Maboneng vision: to be a "mixed-income neighbourhood" where suits and ties could sit side-by-side with dashikis and afros while the thump of drum circles summoned multi-year investment projects.

Or something of the sort.

Maboneng was marketed as the place where creativity comes for a breather—to get nurtured, to regain strength. But the artists who were here when the flagship Main Street Life building opened circa 2010 had left three years later when I arrived. They could see that what they'd been sold was a sham.

They knew.

Today, hardly any art galleries remain, while the few spots that accommodated art-related activities have been razed to the ground, metaphorically speaking. Gallery Fanon sits alone in the Museum of African Design building. The gallery on Kruger Street perished a long time ago; a hair salon occupies its place. Goethe-Institut South Africa closed its project space, and The Centre for Less Good is closed off to the public, bar from days when performances are happening.

The food culture's been decimated.

Look elsewhere for your craft beer and a pizza; or hummus, tahini and avo on rye bread; or steaming lamb curry with a serving of basmati rice; or sushi from Blackanese —the one that used to be on corner Kruger and Main Street, not the transplant, shadow version on corner Fox and Albrecht streets.

Ziggy with his potjiekos; Kassa with his Ethiopian cuisine a few steps down from him; and the braai spot around the corner on Kruger Street have held it down from day one. They are in an elite group; the rarest.

Experimental theatre space, gone. Indie cinema house, gone—bar from a few screenings hosted by Toka Hlongwane's Bantu Scope mobile cinema in the MOAD basement.

In their stead, and especially over the last three years, give or take, a portfolio of lifestyle establishments have risen. Their aim: To generate maximum profits.

On the other side of the funk have been the residents who've had to find creative ways to block out the noise coming from Fox Den, and Shakers Cocktail Bar, and JoJo Rooftop Lounge; the residents who have had to find ways to disengage while punters emerging out of Maboneng Lifestyle Centre at 3am threaten to beat up and kill one another weekly, from Thursday through to early Monday morning.

"Maboneng" and "chaotic" are interchangeable words now. The precinct is a post-gentrification melanoma with a Monday-to-Monday slant that no one can figure themselves out of. And don't bother calling law enforcement, they'll just come and illuminate the scene with their blue lights.

Maboneng as Anti-Black Business People

Maboneng's developers, Propertuity, along with the property management company, Mafadi, have hidden their failures well. It's what makes the liquidation story from 2019 all the more embarrassing. The area's expansion project seemed to be going so well.

But paying attention to the paper trail reveals that Maboneng is anti-small, black-owned business. It's for this reason that establishments such as Main Street Bizzare failed. To single out the one or three success stories is to evade this fact; it's to reduce the plight of many businesses, like those housed in the Bizaare, to a mere footnote.

It's erasure, and serves to excuse Mafadi's failure to respond to the entrepreneurs' repeated requests that there be advertising around the precinct which directs buyers to the area, especially on Sundays when people would descend upon the precinct for the market at Arts on Main—itself a fruitless pursuit because of the endemic neglect and lack of foresight within the establishment.

There was categorical neglect too, maintenance-wise. Business owners had to display their wares outside one Sunday due to broken pipes that let raw sewage run freely throughout the space. Main Street Bizaare was shut down within 18 months of its opening. The space is now occupied by a second hand car dealership.

It would be disingenuous to omit the positives that Maboneng's changing face brought. An increased volume of revelers over the weekend and on holidays meant that Jo had an audience to perform her old school R&B classics to, an attempt to get people to buy her CDs. It meant that Jacob's boerie rolls stall had endless customers. And it gave birth to a burgeoning street photographer scene that has yielded semi-stable income for some.

"They're taking our jobs"

One of the hottakes that used to do the rounds among the wokes at mid-week dinner tables was about how Maboneng had usurped the livelihoods of many a business people in Jeppestown. I tested out this theory by doing what few have thought to do: Speak to the different people living and/or conducting business in the area, ask for their thoughts.

Overall, businessowners were more concerned about the re-emergence of xenophobic attacks than they were about some impending doom wrought upon them by a couple of enterprising hipsters next door. These worries were very real, being that there'd been xenophobic violence the previous year, in 2015. That year's events ripped through the heart of Fox Street one September 2019 afternoon when a fleet of eager troopers set about breaking shop windows, ripping into people's vehicles, and scaring everyone shitless.

The veil had been lifted.

Gentrification is violent and outright ugly. But what commentators have been doing—using gentrification as a catch-all term to explain away endemic social problems that have metastasized due to categorical neglect from local councilors through to national government, coupled with the anti-poor, anti-black neo-colonial fiscal policies adopted by states worldwide—is dishonest, and lacks intellectual rigour.

Maboneng as part of the Jozi inner city experience was a heightened spiritual experience. It revealed the changing nature of the city, and was the unlikeliest site for me to make peace with the impermanence of the moment—any moment.

- South African Women Talk 'Six Inches' In Hilarious Adult Theatre ... ›

- Interview: ZuluMecca Packages Messages From The Ancestors in ... ›

- Johannesburg's Experimental Music Finds a New Home - OkayAfrica ›

- MOAD Director Aaron Kohn Talks Africa's First Design Museum ... ›

- 'Joshua The I Am' Is The Rapper Changing Up South African Hip ... ›

- Johannesburg Street Style: Unlabelled Magazine's 'Shoe Story ... ›

- #katarasessions Is The NPR Tiny Desk Concert Of South Africa ... ›

- 'Dear Ribane' Is the Future Of Electronic Performance Art Music ... ›