Film: '18 Ius Soli: The Right To Be Italian'

Review of Fred Kuwornu's '18 Ius Soli: The Right to be Italian', at BAM's New Voices in Black Cinema african film and african-american film festival

![]()

On November 2011, the national soccer teams of Italy and Romania played an exhibition match. During the game, Italian hooligans (tifosi) repeatedly shouted at the top of their lungs: “Non ci sono neri italiani” (There are no black Italians). Well, aren’t there?

The statistics tell otherwise: in Italy, almost a million young men and women were born to or raised by immigrant parents, and 12.6% of babies born in the county have non-Italian parents. Unlike most neighboring countries and the US, these men and women are denied the right to acquire Italian citizenship by the ius soli law, which results in 42% of them remaining aliens when they turn 18 (the age of maturity in the EU).

This old regulation creates an inequality of rights between young people with Italian parents and those of the 2nd generation. They suffer an array of consequences in their daily lives: from constantly needing to renew their residency, to being denied access to grants and scholarships that their Italian friends enjoy and being susceptible to deportation if they don’t carry their visas with them at all times. This legalized discrimination condemns them to the life of third-class citizens and has led them to lift up their voices in the public arena to provoke legal redress.

This is exactly the case of Fred Kuwornu, the director of the documentary Ius Soli. Il diritto di esseri italiani (Ius Soli. The Right to Be Italian), which premiered in NYC at the third edition of New Voices in Black Cinema at BAM Cinématek. Kuwornu is a producer, filmmaker, activist and entrepeneur of Ghanaian origins who made this film to denounce this incomprehensible situation in contemporary Italy, urging for a response from the political authorities and the judiciary.

Avoiding the stereotypes of victim and outcast, the documentary is organized around interviews of 18 successful young men and women of African, Asian, East European and South American descent. With the intention of breaking down stereotypes and preconceptions of their fellow citizens, we hear how these people, overcoming all kinds of obstacles, have succeed in getting degrees, starting their own businesses and, in many cases, giving their free time to volunteer at the Red Cross and various other cooperative organizations. Their dedication is paralleled by two exemplary historical accounts of excellence and inspiration: those of famous boxer Leone Iacovacci (1902-1983) and partisan fighter Giorgio Marincola (1923-1945). Using archival footage and voice-overs to narrate the lives of these Italians of African descent, the director rescues these two unknown stories from oblivion. In their own way, both Iacovacci and Marincola xperienced racism and fought against inequality, becoming models for new generations.

![]()

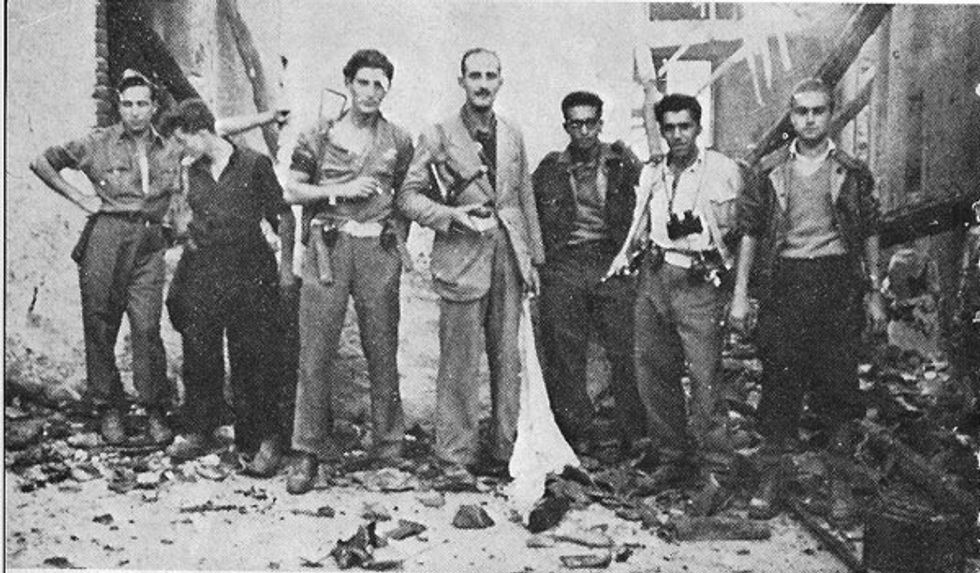

*Giorgio Marincola, third from left

Leone Iacovacci, born of Roman father and Congolese mother, became a professional boxer who toured the world, changing nationality to suit his interest, until he returned to Europe to win the European boxing title as an Italian and provoked the ire of the fascists, who could not bear to see a black person wearing the maglia azzura (the blue t-shirt that has represented Italy in sports since the time of the Savoy dynasty). Giorgio Marincola, born in colonial Somalia, came to Rome at the age of 10. He dedicated his short life to defending the principles of justice and freedom, following the lessons of Pilo Albertelli, a high school teacher of history and philosophy and a famous anti-fascist intellectual. His early encounter with the humanists precipitated his decision to join the partisan forces. When asked why was he fighting for a country that shortly before had colonized his people, Marincola answered: “Homeland doesn’t mean a color on a map but freedom and justice for all the peoples of the World”. He died at the age of 20, killed by Nazi forces, but his is an indelible testimony of strength and conviction to effect change.

The lives of their contemporary counterparts might not look as legendary, but they're familiar to anybody who has had to suffer the dislocation of migration and struggle to make a living in a foreign country. The subjects have complex identities, as we come to know listening to their opinions and circumstances. The experience of each is rife with the contradictions provoked by the constant refusal of the administration to recognize their Italian citizenship, while they speak, eat and feel “Italian.” In the words of a 2nd generation Italian at the beginning of the documentary: “We are not immigrants, we don’t come from another country, we haven’t crossed borders. We have been here since the beginning of our lives”.