You Need to Hear This Mixtape of Vintage, Golden Era Sudanese Music

Ostinato Records founder Vik Sohonie shares details on his upcoming compilation of sounds from Khartoum and Omdurman.

In a meeting with Djibouti's minister of culture in late 2016, we discussed Somali and Afar music from his country. The conversation gradually grew to East African music culture at large and when I asked if he enjoyed the music of

Mohamed Wardi, a Sudanese legend, he placed his phone down, adjusted his glasses, put his hands into the heavens and said "Wardi!," as if to imply that we mere mortals have no business speaking so casually about a singer, composer, poet, and activist deified across much of Africa and the Arabic speaking world.

Such is the reputation of Sudanese music, particularly in East Africa and what is often referred to as the "Sudanic Belt," a cultural zone that stretches from Sudan all the way west to Mauritania, covering much of the Sahara and the Sahel, lands where Sudanese artists are household names and Sudanese poems are regularly used as lyrics to produce the latest hits. Sudan is a land of poets. When protesters take to the streets of the capital, they read poems.

One old school producer told us that his cassettes often sold more in Cameroon and northeastern Nigeria.

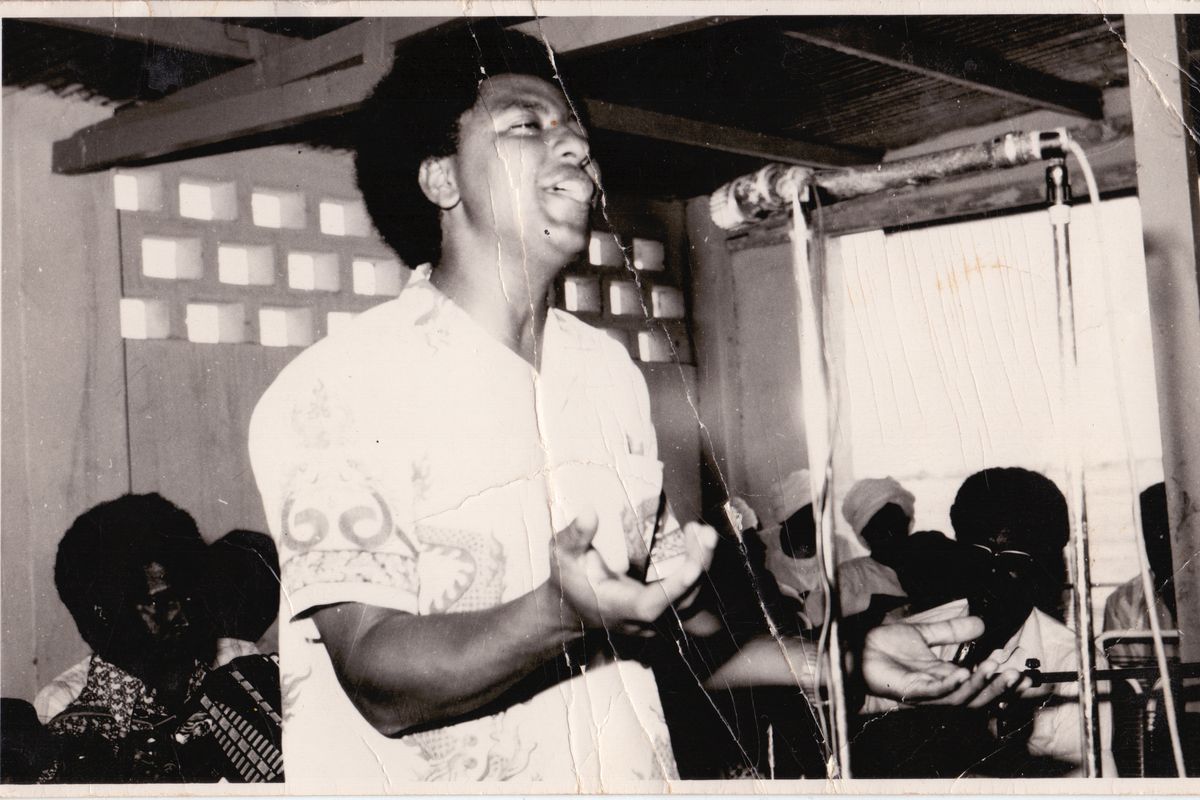

Musicians in Ethiopia and Somalia frequently point to Sudan's biggest golden era stars as sources of inspiration. The likes of Mohamed Wardi and Saied Khalifa toured regularly, serenading sold out crowds in Mogadishu, Addis Ababa, Asmara, Cairo, Tripoli, and the Persian Gulf States.

At one concert in Mogadishu in the 1970s, women threw their expensive jewelry onto the stage as Wardi performed.

I remember how emotional one Eritrean cab driver in Seattle became when we began speaking about Sudanese music. "The way they play," he said choking up, "it's like no other."

The 10 Best African Poems of All Time

These are the lines that have woken imaginations and stirred souls across the continent and beyond.

It should baffle anyone, then, as to why and how a music so universally adored across the African and Arabic speaking world never garnered global recognition. Indeed, some musicians, like Abdel El Aziz Al Mubarak toured farther than most of his counterparts, with stints in London and Tokyo, but he was the exception rather than the rule.

Perhaps one explanation is a common misconception: to speak of 'Sudanese music' is in itself incorrect. The diversity of Sudan is difficult to quantify, with 70 languages spoken and the capital city Khartoum teeming with all hues.

The music, naturally, is the greatest reflection of an often unspoken plurality. There's Shaigiya and Nubian music in the north, Fulani music in the west, the Soukous-esque sounds of what is today South Sudan, the jazz music of Omdurman (the old capital), which our friends at Habibi Funk have been exploring deeply, the endlessly gorgeous violin and accordion driven orchestral music of 1970's Khartoum, and the synthesizer music of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But it's the orchestral music, filled with pentatonic scales, tum-tum rhythms, and violins played in ways "like no other" that captured the hearts and minds of post-colonial Africa and the Middle East.

Another, even more legitimate explanation for the isolation of the many musics from what was once Africa's largest country, is that, as a scholar in Khartoum told us, "In Sudan, the political and cultural are inseparable." Colonization by the Ottomans, the Egyptians, and the British, the concentration of political power in the oasis of the capital, Khartoum, at the expense of the rest of the country, and an economy badly tampered with by both London and Washington, D.C., have condemned Sudan to perpetual political dysfunction, with highs and lows that directly affected the arts. The highs, under leadership that protected and promoted music, helped give birth to one of the richest music scenes anywhere in the world. The lows, under hardline religious leaders, were defined by regressive edicts, censored lyrics, burned recordings, almost killing music entirely, and, in some notable instances, musicians as well.

One of the most prolific recording industries—not just in Africa, or the Global South, but the entire world—has been constrained from strutting its auditory heritage on the global stage. Forty years later is more than just overdue, it's a travesty of cultural justice. But perhaps perfectly timed as sanctions have been lifted and the people of Khartoum take to the streets to demand change.

Due to the troubled era of the 1980s, when Hassan Al Turabi's hardline religious authority swept the country, recordings in Sudan are difficult to source. This project has taken Ostinato's team to Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Egypt in search of the timeless cultural artifacts that hold the story of Africa's most mesmerizing and welcoming cultures. That the music was mainly found in Sudan's neighbors is a testament to Sudanese music's widespread appeal.

But we're taking it one step further. In partnership with famous poet and actress, Tamador Sheikh Eldin Gibreel, we're going to bring the enchanting harmonies, haunting melodies, and relentless rhythms of Khartoum's golden cultural era to the world later this year, fully remastered and licensed.

Take a sail down the Blue and White Nile as they pass through Khartoum, carrying with them an ancient history and a never-ending stream of poems and songs.