Africa in Brazil: How Ilê Aiyê Brought Blackness to Salvador's Carnival

Salvador's carnival, once a white-only event, was reclaimed by black Brazilians looking to celebrate their African heritage.

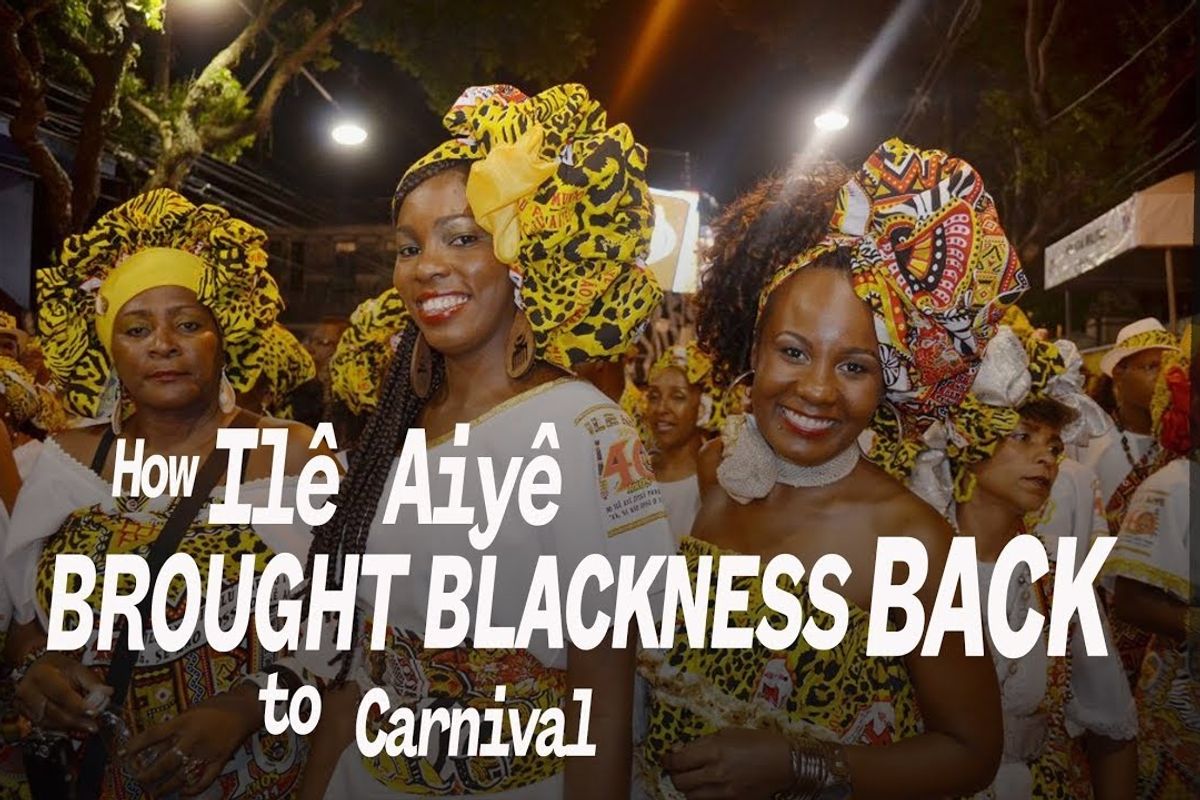

Those unfamiliar with the Ilê Aiyê(pronounced e-lay ah-ay) group, might assume its members come from Nigeria or Benin. The headdresses the women wear could be found at a Nigerian wedding. The cloth of their costumes sport the bright colors typical of wax cloth. The music is driven by just drums. But few people in this group have ever visited Africa.

Ilê Aiyê was the first Afro-Bloco carnival group in Salvador and in the last 44 years, it has helped black people across Brazil to reclaim their African heritage in a positive way. Of the city's 3 million residents, more than 80 percent identify as black. Their heritage is a legacy of Brazil's transatlantic slave trade, which brought more than 2 million Africans to the coasts of Brazil.

Although Salvador, Brazil is a majority-black city, its mainstream carnival had evolved into an event for whites by the 1970s. Back then, as it is today, Salvador's carnival was dominated by blocos that followed moving sound systems—trio-electricos. White Brazilians danced to these trio-electricos while black Brazilians held a cord around them to prevent poor people from entering their space.

At the time, it was considered dangerous to create a carnival group that exalted blackness and only included blacks. The dictatorship always squashed any efforts by blacks to organize against racism. But this didn't stop a circle of black friends, who, while coming back from a day at the beach, decided to create a carnival group with just black people—Ilê Aiyê.

“We're helping black people build their self-esteem," said Vovô do Ilê, the leader and one of the founders of the Ilê Aiyê carnival group.

Vovô and 100 other friends created Ilê Aiyê in time for 1975's carnival. During that year, they dressed in red, yellow and white fabric and paraded throughout Salvador to the song of Que Bloco é Esse - What is this bloco? For the following year, the group chose a theme—the Tutsi people of Rwanda. Since then, Ilê Aiyê has honored more than 20 African and Caribbean countries during carnival. This year, the group will celebrate 100 years of Madiba: Nelson Mandela.

Ilê Aiyê was born in a house of the Candomblé Afro-Brazilian religion. The mother of Vovô, Mother Hilda, reigned as the Candomblé priestess of the Ilê Axé Jitolu candomblé house until her death in 2009. So the influence of the Afro-Brazilian religion on the cultural group is very strong. It can be heard in the rhythms of the drum section and the lyrics of the songs. Even the name Ilê Aiyê comes directly from Yoruba—the roots of Candomblé. Ilê Aiyê generally means the "Black World" by black Brazilians. To this day, the Ilê Aiyê has the most members of any Afro-Bloco who practice the Candomblé religion.

In those early years, Ilê Aiyê fine-tuned its identity. That identity eventually came to define the genre of the Afro-Bloco: A Yoruba name exalting blackness. A large drum section providing the musical foundation; Songs whose lyrics promoted Brazil's African heritage; Fantasias made of a fabric highlighting the year's theme. In 1979 the Afro-Bloco fever spread to the north of Salvador. Black Brazilians in Itapuã created the Afro-Bloco Malê de Balê, which paid homage to the African Muslims who led the greatest revolt against slavery in Brazilian history. Blacks in the center of Salvador created Olodum, an Afro-Bloco that Michael Jackson made popular in his video "They Don't Care About Us." Today there are more than a dozen Afro-Blocos in Salvador and their music, dance and fashion are the foundation of Salvador's "black" carnival. Black communities in cities all over Brazil and the world have also created Afro-Blocos.

White beauty has always been the standard in Brazil, so much that even today it's rare to see dark-skinned women fronting advertising campaigns or winning beauty pageants. From the beginning, Ilê Aiyê always promoted dark-skinned black women as beautiful, and divine. In 1979 Ilê Aiyê held it's first Beleza Negra beauty pageant to choose a Deusa de Ebano "Black Goddess" who would reign as the queen of the bloco.

"Ilê Aiyê is showing us our beauty and our importance," said Jessica Nascimento, 19, the winner of this year's Beleza Negra beauty pageant. "We don't even recognize this ourselves."

This year the pageant celebrated its 39th edition with 16 women competing. In a program lasting four hours, contestants are judged on their representation of the year's theme and how well they dance. Nascimento will represent Ilê Aiyê during carnival and in concerts across Brazil and the world.

"We see black women being represented as a goddess," Nascimento said. "Black women aren't in these places where they are the protagonist. Ilê Aiyê brings a social and political conscious to the table in addition to the beauty."

The highlight of the beauty pageant is when each competitor dances the Black Goddess dance. In this dance, competitors show what they are feeling through the dance.

*

Watch "How Ilê Aiyê Brought Blackness Back to Carnival" above.